Alban Hajdinaj

Back Side Collections

Rome (I), Galleria Traghetto

December 2009 ― January 2010

Just behind the surface

Daniele Capra

Si voir et savoir étaient bien les grandes interrogations éthiques et esthétiques depuis le siècle des Lumières, voir et pouvoir deviennent celles du XXIe siècle.[1]

McDonald’s, Levi’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Puma. All these companies have something in common, apart from being multinationals, often criticised by those who desire a more responsible approach to consumption, or more care for social and environmental values: they all base much, if not all, of their communication strategy on the recognition of the brand, the colours, the logo- all the elements which are able to give added value to the products they sell. The mechanism is quite simple- a graphic symbol or writing- or more often the two together- are reproduced millions of times and cleverly distributed through various means, from packaging to glossy magazines, on the streets, through sports sponsorship, on television and so on.[2] This overwhelming use, whilst it gives great commercial strength and power, also causes a progressive wearing and erosion of the iconic value to the brand, which becomes a different thing, a symbol which exclusively manifests the identity of the company. It is a kind of formidable commercial reminder which in reality makes the original image aphasic.

Alban Hajdinaj works in opposition to this dynamic of consumption, in particular in a series of works with ‘acrobatic’ titles (one of these, for example, is L’origine de la gauche et de la droit for the Levi’s logo, where two horses pull a pair of jeans in opposite directions). These works seeks to visually re-appropriate images which have for too long been exclusively in the hands of the skilful manipulators of marketing. The Albanian artist makes a tabula rasa of the communicative superstructure built on the brand, stripping the value of the image bare. It is a conceptual process, the elimination of value and the anaesthesia of meaning, entirely in line with the practices of new dada. Rauschenberg asked De Kooning to make a pencil drawing which he then erased with a rubber, but Hajdinaj has the logos of large multinationals already waiting for him, and, if we look carefully, also those of small shops and local companies. His approach is not necessarily a protest or political in nature, but rather a more ironic manifestation of a subversion of the status quo. The way he does this varies each time, from sinking in the indistinct (where the logo is covered with the same colour as the background so that it appears to be somehow confused with the surface), to a more playful re-adaptation creating an iconic semantic shift. Thus the bearded colonel of Kentucky Fried Chicken enjoys himself as a gondolier on a paper napkin, or posing for a portrait with a red pinny, or the cockerel of Le Coq Sportif preens on a shoebox. In this way, in a world where “the violence of the shock of the image seems to be the only means of expression, the objective work […] emerges as an act of resistance. […] Once again activating the emergency brake without which no culture can last”.[3] Hajdinaj dismantles the meaning- or the attribution of meaning- carried by the brand and regresses the image to a primordial state. This is a significant opposition to the vortex created by consumer society where the images have a clearly defined use and are, obviously, protected by copyright. All of this is characterised as an act of protest, primarily of an aesthetic and phenomenological nature.

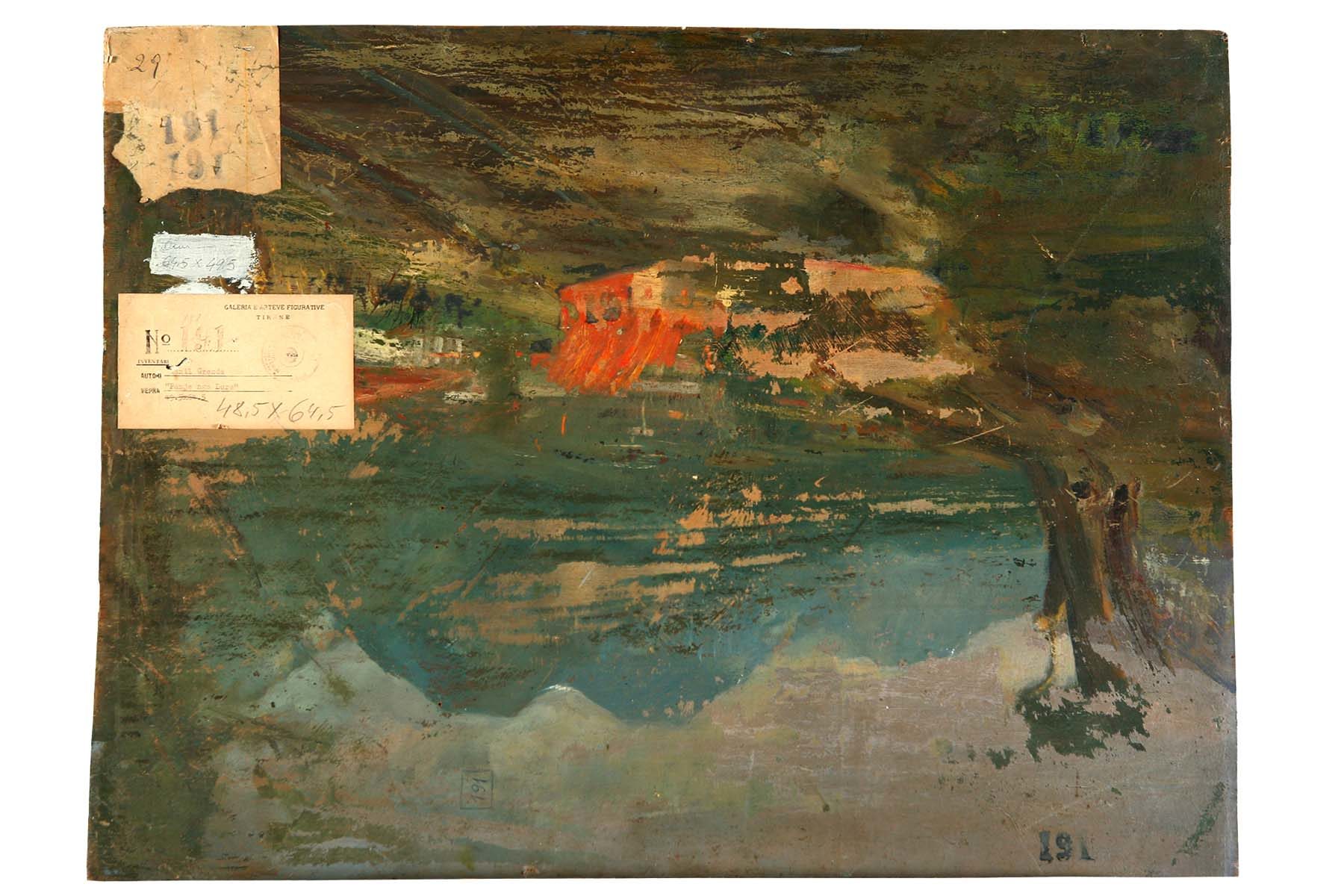

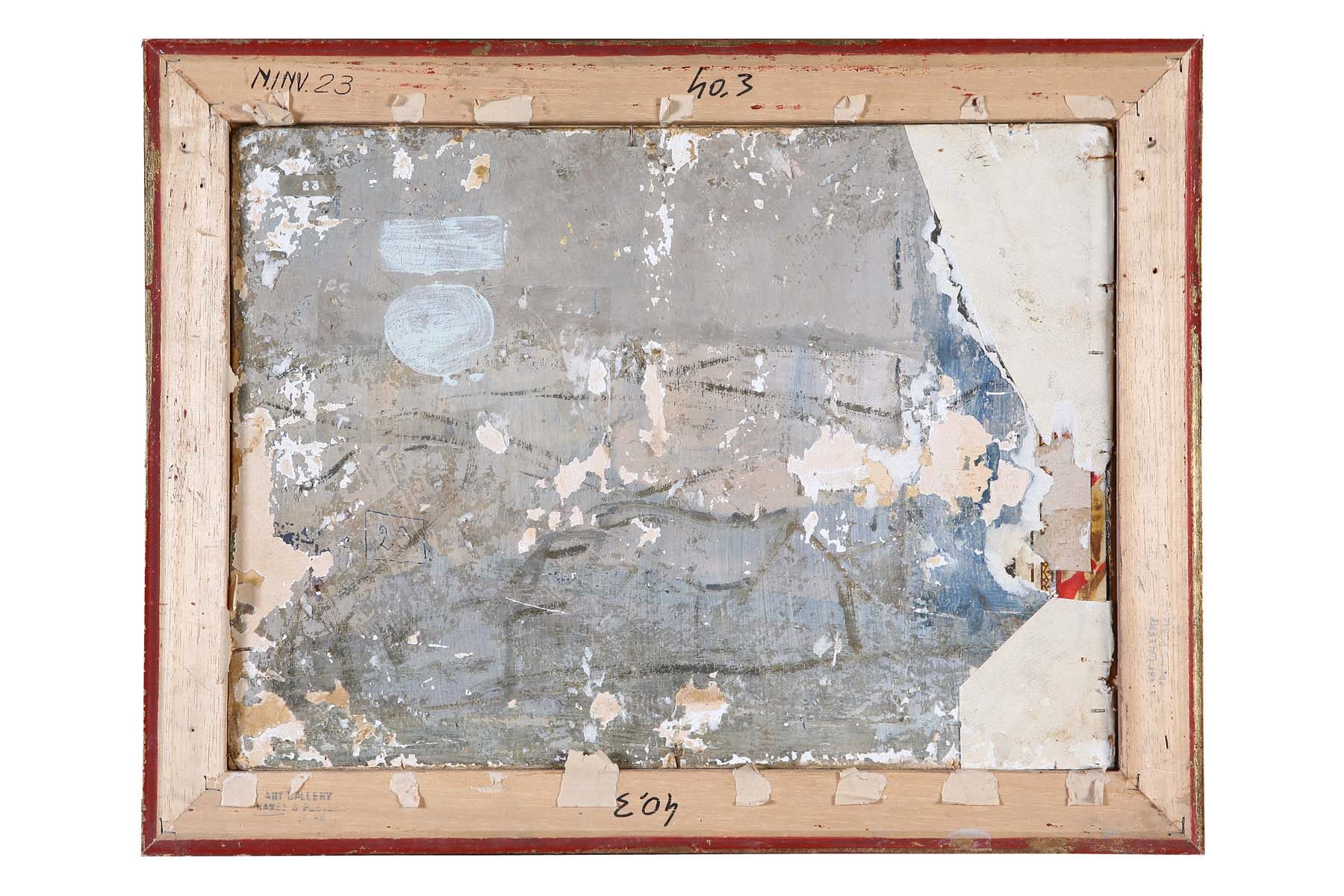

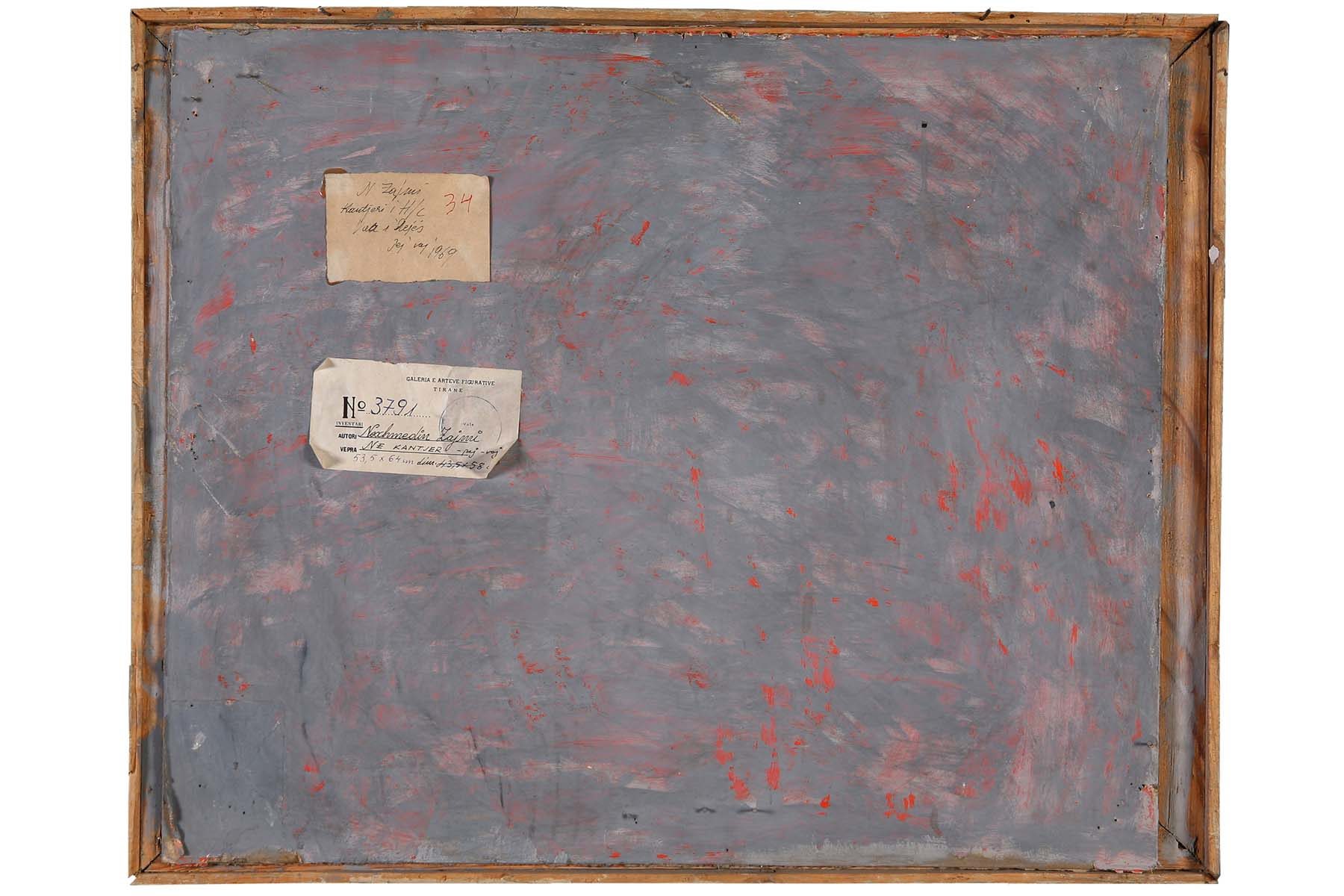

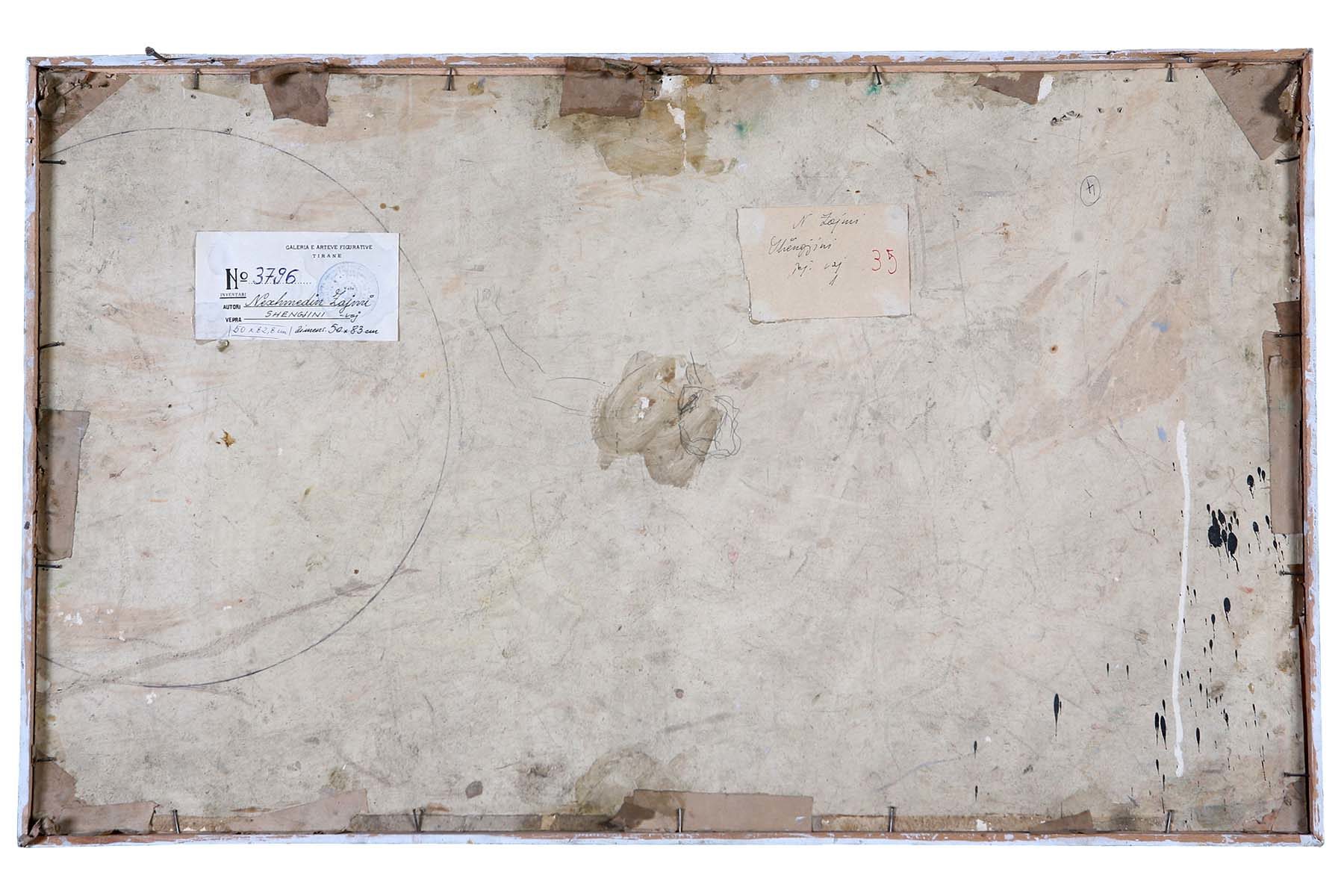

Both these anti-drawings, and the series of ready mades made with the torn pages of school books (where children have drawn on the illustrations), and also the complex project which led him to photograph the backs of canvases hanging in the National Gallery in Tirana, bring Alban Hajdinaj’s work within that which Nicola Bourriaud sharply defined as postproduction,[4] where “objects already informed by other objects”[5] because ex nihilo creation is no longer possible, since the ideas of originality and invention have now completely collapsed.

As such, Hajdinaj’s art- both to show itself, but also to exist- needs the physical and ontological support of the complex world of objects, which they ultimately feed upon. The use of objects trouvées thus becomes a kind of cannibalism of reality, however it is moderated by a desire to show that which is normally behind the iron curtain of superficial vision, which is so often the only kind of vision used by the homo videns living today.

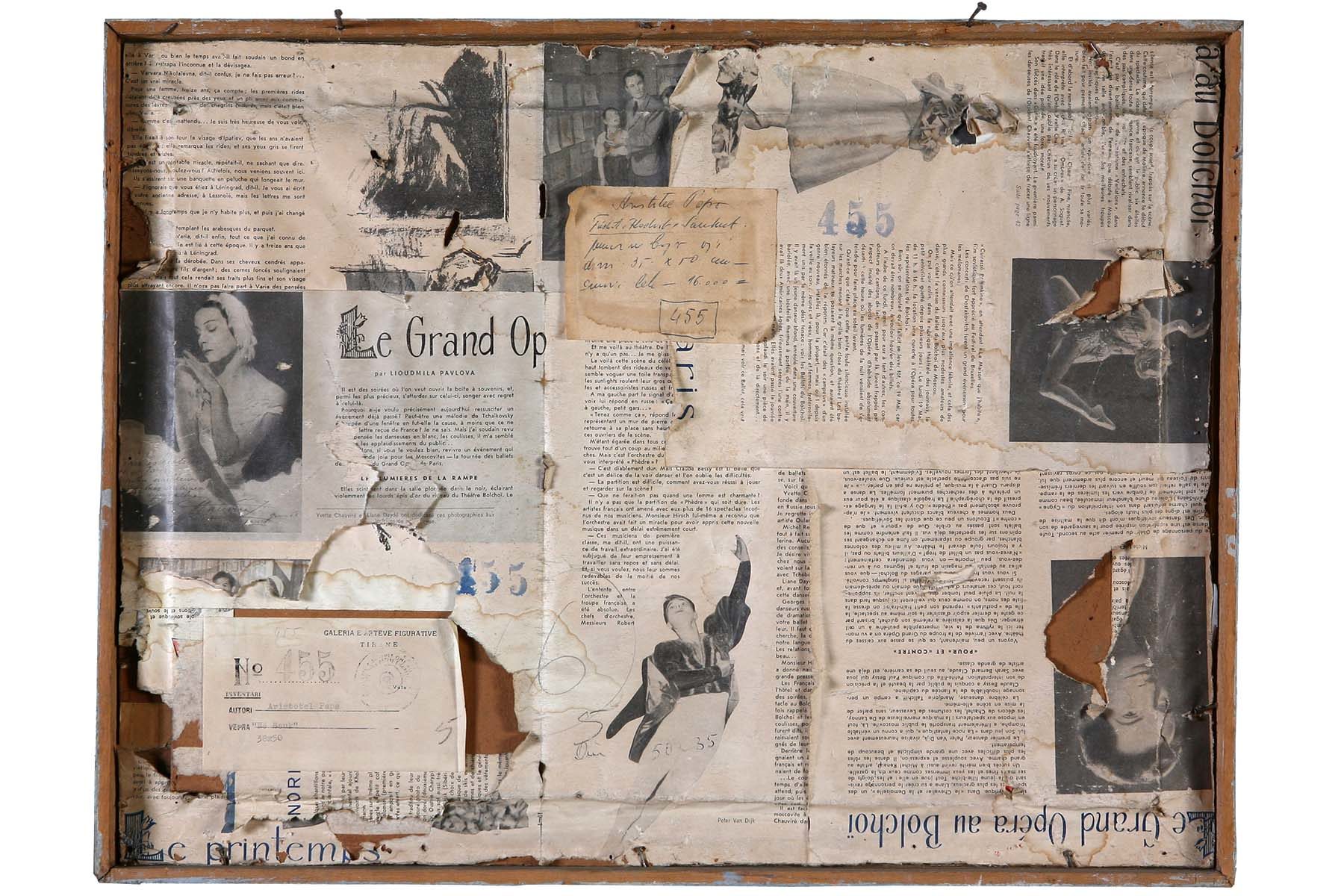

Overturning the point of view, whether it be topographical or conceptual, is at the root of the project the artist created at the National Gallery of Tirana. Here the paintings were photographed to create a genuine census of the works present. However the photographs were not of the displayed side of the paintings, the well-known images the viewers normally see, but rather the backs- that is the side which only the walls know. As such Hajdinaj created a personal collection of images- existing but hidden and never shown (and thus inexistent in the age of information)- which were printed at life size. In this way the artist showed how it is possible to get juice even from the wrong side of the orange, and at the same time show all of that which is hidden from our gaze because it lies behind the hedge, if not the hedge itself of Leopardi’s poem.[6] However, the backs of canvases often show signs of other uses (for example sketches or preparatory drawings) and the various labels which record sizes, presences, movements for shows. Having all this information makes a kind of anti-history for the artwork possible, not official, although sometimes not unknown to a historian who has studied that particular painting. Thus, once again, the process put in motion by the artist allows a small but substantial subversion of the everyday we are surrounded by.

The video Uomo Vogue is a work about being an artist and about being publicly recognised as such (with all the stereotypes that implies). This is a kind of self-aware performance by Hajdinaj recorded during a photo shoot where Michel Comte took the artist’s portrait for Vogue magazine. A noisy crew arrives in the artist’s Paris apartment to get him ready- makeup, hair, wardrobe- to make him look his best, or his coolest: that is, making him into the image we recognise as an artist, a status he can be proud of. This is followed by the shoot, in strange and unnatural poses, with the famous photographer holding in his hand the release cable connected to the shutter. Then the lights and the set are taken down, and the whole performance finishes with front door closing. The artist seems drained, tired, as exhausted as a theatre actor after the curtain falls, unsure of his legitmate identity and that taken on with such effort on stage. But here no one is going to applaud, because, for the general public, the portrait on the film, reproduced on glossy pages, will be the most desirable version of the truth.

[1] P. Virilio, L’Art à perte vue, Paris: Éditions Galilée, 2005.

[2] See N. Klein, No Logo, Toronto: Knopf Canada , 2000, “since many of today’s best-known manufacturers no longer produce products and advertise them, but rather buy products and “brand” them, these companies are forever on the prowl for creative new ways to build and strengthen their brand images”.

[3] P. Virilio, L’Art à perte vue, Paris: Éditions Galilée, 2005.

[4] See N. Bourriaud, Postproduction, New York: Lukas & Sternberg, 2002, p. 7, “an ever increasing number of artworks have been created on the basis of preexisting works; more and more artists interpret, reproduce, re-exhibit, or use works made by others or available cultural products. This art of postproduction seems to respond to the proliferating chaos of global culture in the information age, which is characterized by an increase in the supply of works and the art world’s annexation of forms ignored or disdained until now”.

[5] N. Bourriaud, Postproduction, New York: Lukas & Sternberg, 2002, p. 11.

[6] See G. Leopardi, ”L’infinito”, in The Canti, with a selection of his prose, trans. J.G. Nichols, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 1998.