Eloisa Gobbo

Safe Trip Home

Padua (I), Spazio Tindaci

February ― March 2009

Unsafe Home Trip

Daniele Capra

Then there was an astonishing, unexpected arriving of the dark. And with the dark an icy wind that broke the desert. The Benzedrine was going to leave me. [1]

You can’t travel standing still. Or perhaps so: the slothful Pessoa docet, and all the literature – if we would go to the extremes in a way neither too much peculiar, could be summed up in the unique purpose to make us moving, moving only the eyelids. It is as moving emotionally, conceptually, politically. All the rest can be considered chattering, the real movement of the reader is a false standing still, as like who is very keen on art, aims to be kinetic in front of the work only with the sight, the hearing and the thought. And than why makes a trip towards home, like that one which gives the title to this exhibition?

It’s easy to explain. This trip doesn’t exist. It is a Pindaric flight of a centimetre, a flight that Eloisa Gobbo invents and manages with strict obstinacy. As if it would be full stop and new paragraph. It is a flight over a broom opportunely prepared to bring us in a reality of pictorial invention, of things not true and neither probable: a world that without the arrogance of the self-reference, tries to be self-sufficient, a matter which independent, stays in the world. She isn’t the Safe Trip Home, which gives the title to the exhibition (after many years, the artist exhibits in her city again) but a Home Trip, a non trip projected in her studio with brushes and acrylic colours. Unexpectedly more daring.

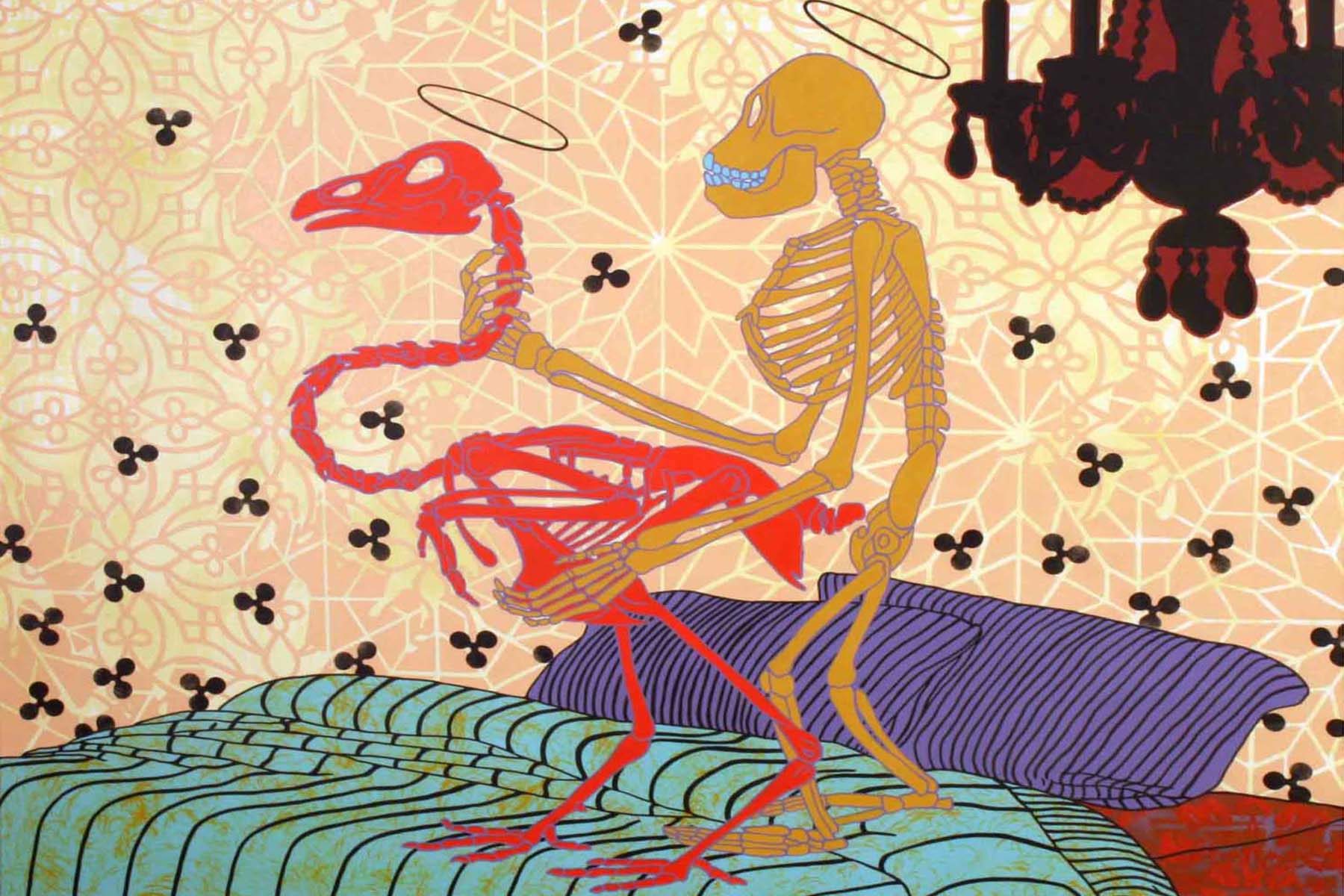

Many are the matrixes, whose could bring back to her painting. There is a development of plans and grids, which overcome at levels and repeat seriously, in a rhythmic way. The reiterations of similar structures, often with micro differences not visible at the first sight, make her canvasses look like the Anglo-Saxon trip hop, to Tricky and her velvet trips between samplers and sequencers, to the soft hallucinations produced by nice psychotropic substances. We can recognise the use of figurative elements but also the anionic and anti-naturalist treatment of the colour, sometimes in a wider association, sometimes showily in an acid contrast.

Composed in an additional way, as elements sum from the most varied iconographic origin, (but the same talk can be done in the case of the carpets) her works on canvass are born from the visual super exposition and from the retinal hyper stimulation, which distinguish the image of the age we live in. And if the images haven’t by now a rule not different from that – debases – of muzak, of easy lounge music for voracious and bored consumers, it is difficult to look for univocal motivations of this continues elements turning, which are lend from the web, from the design, from the graphics, from the botany, from the ornamental decorations of the western and oriental tradition.

The presence of anionic and figurative elements in the Eloisa’s work, explains us the poor value of the taxonomy, with which we usually mark all the painting and authorize us to think that this kind of antinomy is only chattering for authorized staff, who deals quickly. In the other hand “abstract or figurative”, as deduces in the San Romano’s Battle painted by Paolo Uccello, the pictorial reason becomes object of a filtered representation from an eye progressively investigative, which makes Leonardo da Vinci to affirm, that the painting is a mental thing”.[2] How to object it?

Her work, in her not concealed decorative lightness, is, in fact, full of an hidden seed: to be painting from painters, that in the thought pretends, where the practise is concrete and almost a late display in a universal reality of signs and returns, which has the priority in the visionary artist’s fund, and that finds in the reality only a line support to fill in, after having emptied her own pack-saddle. In fact her way of going on doesn’t aim, as every shape of post-modern representation, “to represent the world things, but to reproduce instead the ways and the styles of the representation”.[3] The weight of the téchne can’t be cancelled, neither the artist is tempted to do it: only that the space of the research, such as in a work that doesn’t hide the own decorative aspect becomes essentially metalinguistic and the signs often result to be contemporarily symbols and stylistic elements.

One of the most interesting key of reading for a so planned work, has to be searched in the pictorial composition like a contemporary hyper text with life, link and own images, which interfaces directly to the addressee, without mediation, without rules of enjoyment, free and casual like the web surfing. It is so, in fact, that the artist “takes possession of the language and of popular and common styles, to make them strangely sharing of problems more important and complex, and do it so it finishes to provoke a short circuit in the usual schemes of the images communication”.[4] And so flowers, dragons, snakes, even fishes, birds and shells, populate her compositions from the retinal stinging impact, they don’t represent us, if not only with the whole links and windows that can be opened in our visual – neuronal browser.

It is frequently, in the Paduan artist, the use of the writing inside the visual surface, so that we often find declared – in the canvasses and in the carpets – the title of the work. The works are, in this way, enriched of inscriptions, which distinguish themselves as aphoristic decisions, which do like conceptual counterpoint to the universe of signs and subjects, which lives in. In this way it is stronger the interaction of the themes (referable to the triad love/sex/time), that sometimes catch fire like gunpowder, especially when they touch hot points such as the religion or the prostitution, for their provocative and irritating nature. But “the image is always sacred” [5] and distant, far on the wall, needless to say that the lighter is on the hands of every observer.

[1] Edward Bunker, No Beast so Fierce, Norton Press, New York, 1973.

[2] Achille Bonito Oliva, Gratis a bordo dell’arte, Skira, Milano, 2000, p. 18.

[3] Thomas Mc Evilley, The Exile’s Return. Toward a Redefinition of Painting for the Post-Modern Era, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993, p. 102.

[4] Maurizio Sciaccaluga, To Read Carefully the Instructions, Catalogue of the Exhibition, 2006.

[5] “The image is always sacred […] and sacred means separated, puts in distance, sets apart, what that for it itself stays far, intangible”, Jean Luc Nancy in The Three Essay on the Image, Cronopio, 2007, p. 23.