The reality of our own lives

conversation published in the book by Nico Covre Extra Ordinario Mixtape

Vulcano edizioni, Venice, June 2021

ISBN 9788894634204

The reality of our own lives

A conversation about the experience of Extra Ordinario

Daniele Capra, independent curator

Carlo Di Raco, professor at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice

Paolo Pretolani, artist Atelier F

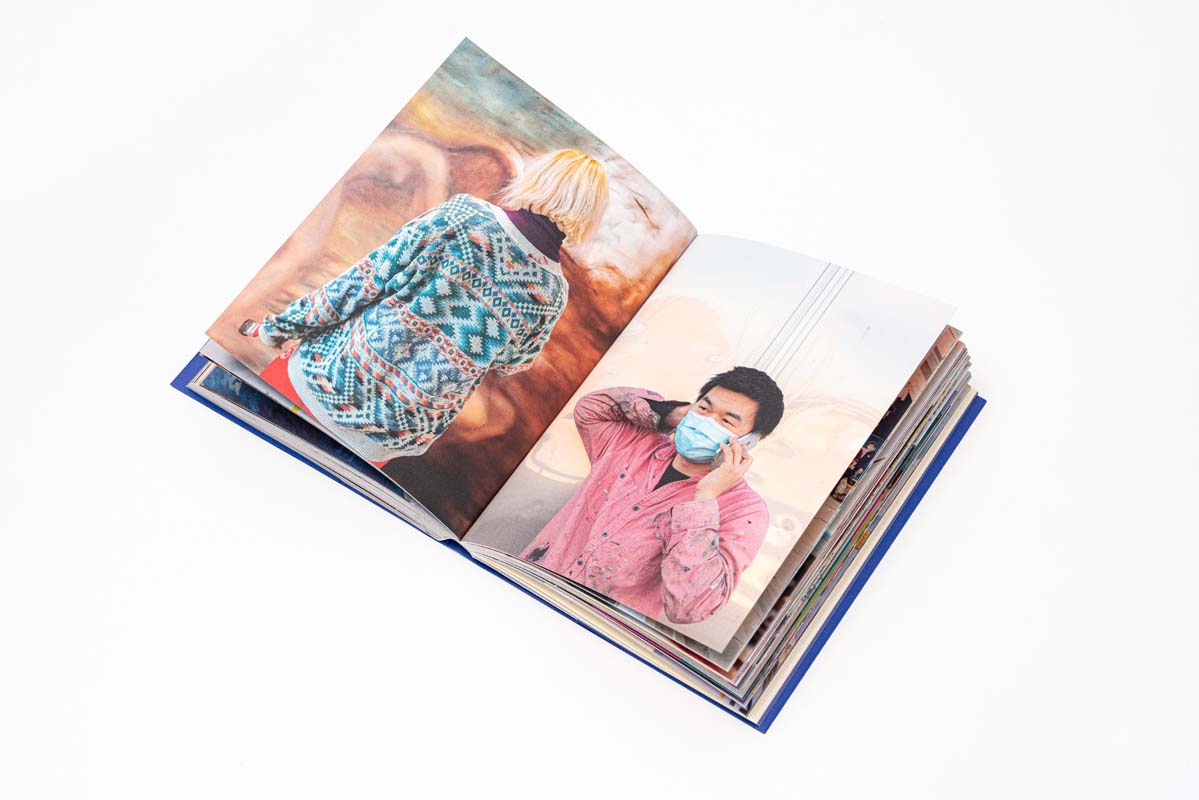

Daniele Capra: When we met in July 2020 I never thought that in just a few weeks it would be possible to do what Atelier F and Vulcano have achieved at the Antares industrial space. We have certainly been affected by the individual and collective impediments caused by the pandemic, but also by the complete removal of any expectations we might have had, as we focussed on resisting and getting around the difficulties in the face of a dramatic absence of prospects for the future. Extra Ordinario was also launched as a reaction to the deaf ear the Accademia di Belle Arti [Fine Arts Academy] in Venice turned to the needs of its students. For months they had no access to the workshops and were forced into largely ad hoc distance learning. I was also amazed at the fact that the students did not start protesting against an institution that was denying them the right to grow. The artists needed to reclaim a space to work together.

Carlo Di Raco: Fine arts academies owe their very existence to the vitality of the artistic research undertaken by their current and former students and staff. For example, we only need to think of what happened at the Leipzig School, which from this point of view is an example that everyone recognises. In general, we would therefore expect them to focus on the more dynamic situations where young artists become the protagonists, and certainly not to be trying to oppose their actions, their vitality and their desire for research, which is what we saw at the time.

Paolo Pretolani: I graduated in July 2020, along with many other young artists. We then had to decide what to do about the summer workshop: on the one hand the workshop Laboratorio Aperto in Forte Marghera was quite a complex situation, as we had seen in previous years; on the other hand there were all the problems related to the regulations to control the spread of Covid. So, even though it might have made sense to launch into a polemical, political debate, we decided it was better to focus on finding an alternative solution, on finding a way to realise our most important project.

CDR: Perhaps it should be said that students and young artists nowadays do not feel the need for any particularly political commitment. They may feel political with regard to the subject of their own research, but they do not feel any need for public action, preferring to focus on the development of the individual expressive elements. I understand this position to a degree, but I do think that if some action had been taken, perhaps we would not have seen such great indifference and inaction by the world of politics towards issues of education.

DC: At this point it is interesting to note that help came from a private organisation, in this case Vulcano. The company not only made the physical spaces available, but also provided organizational and creative resources. It seems to me that it was an excellent opportunity for this creative company to communicate their ideas with the outside world and show what they are about. It was in some way also the first opportunity to see the potential of Antares, an industrial space from the 1920s which Vulcano, and the companies in the group it belongs to, had been considering for use as offices before the pandemic. A project that I think will now have to be reconsidered.

CDR: The private sector has always bought new stimuli to the Accademia di Belle Arti, and the workshop with the artists of Atelier F at the Antares building is not the first example of such a collaboration. There have been previous projects with other important organisations, such as the Pinault Collection. That project saw Urs Fischer, a renowned artist, know for his ability to engage with the contemporary world, create one of his most beautiful pieces together with the students as part of a solo exhibition at Palazzo Grassi. They worked side by side, in the courtyard of the Accademia.

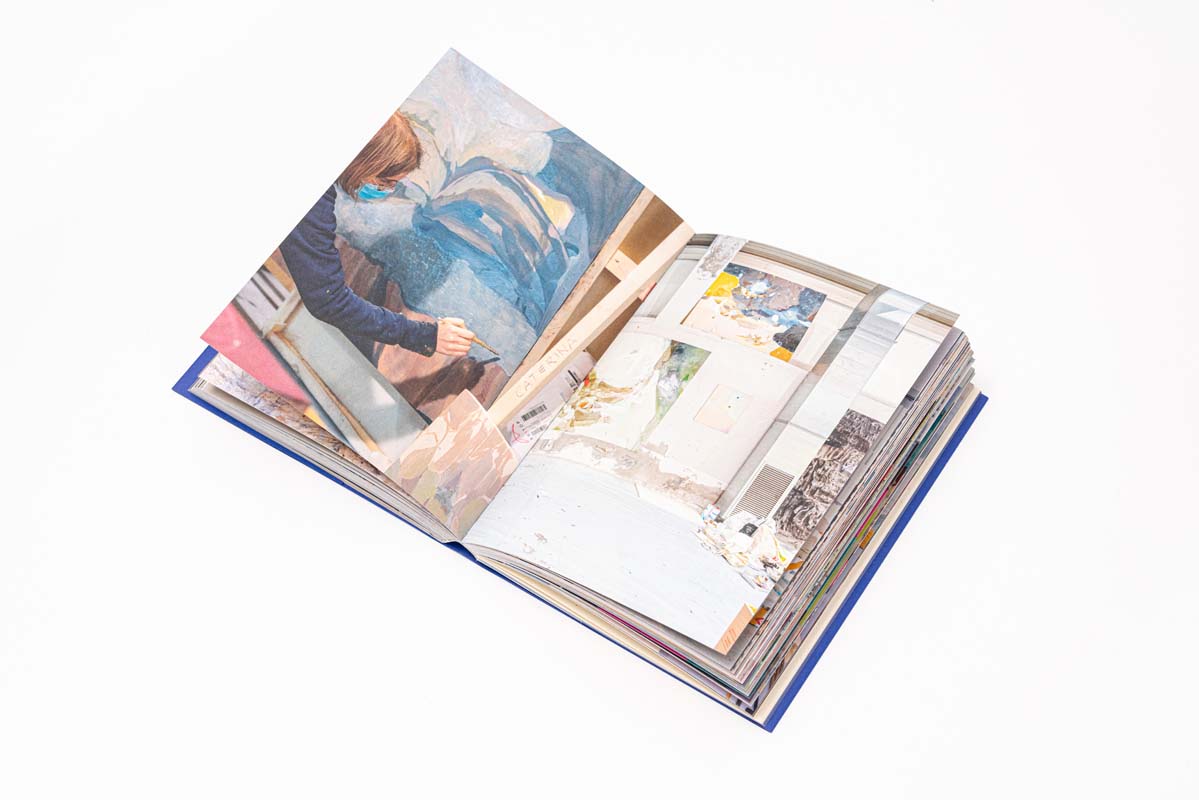

PP: With Extra Ordinario, we, the artists of Atelier F, also tried to re-imagine our way of working, while respecting the practices of the previous years of the Laboratorio Aperto in Forte Marghera. One aspect that remained similar was being able to work in large dimension, which it is not possible to do at the Accademia. That said, we were already used to organising ourselves independently, working day or night, depending on what time was available and the constraints of other jobs that we were doing to pay rent or buy materials. Here, on the other hand, we were dealing with a different partner, and we had to respect precise times, something that perhaps made us pay more attention to time management and be more aware of it.

DC: What are you referring to in particular? Having a scheduled daily rhythm? I have always thought that artists take all the time they need, even to make mistakes, but that they consider time to be something that is infinitely abundant.

PP: I think that having to stop in the evening was a problem for some of us. But I imagine that many of us benefited from having deadlines, finding ourselves in a position of not having “all” the time in the world, but simply “some of” the time. I am reminded of Federico Fellini, who said he did not believe in the absolute freedom of artists. He said that if he hadn’t had the pressure from the producers to finish his films, he would have gone on making the same film for a lifetime. It is not quite the same thing here, but for a young artist knowing that there is a deadline can provide the energy and concentration necessary to avoid getting lost. All the more so because sometimes taking too much time leads to the good ideas you started with beginning to stink.

CDR: Our creativity develops in a dialogue with time, or sometimes in competition with it. Not as an illusion of there being no limits, as it might seem. In terms of teaching, this aspect is even more relevant for young artists who are growing and developing, given that, in the end, a workshop is a situation that intensely concentrates research activities into a given time. I think this is even more important if we consider the context, the collaboration with Vulcano and the perception of having a common goal, in a shared and in some way harmonized time.

DC: I think time limits and deadlines are daily issues to be dealt with even in a company like Vulcano, where I imagine these aspects are somehow planned or standardized. In general, time is calibrated as part of an evaluation that must also consider economic aspects in respect to starting and finishing a project. Valentino Girardi, founder of Vulcano, told me how surprised he was when he asked “how long before you finish your artwork?”, and most of the time the artists answered that they had no idea.

PP: The question of limits is an open question for an artist, not only in terms of time, but also regarding the available space, the material and the imagination. As an artist there is a logic that you learn by growing and continuously measuring yourself through new works. It is a kind of intelligence, which is acquired physiologically by managing and negotiating the relationship with the work. It is an exploration of all the possibilities together with the awareness of the limits.

DC: I think these ways of conceiving work are important for companies. In my opinion the intelligence you are talking about could also be applied to businesses. For example, the experience of Extra Ordinario suggests a way that painting can become a tool for reconsidering the ways in which work is imagined or carried out within companies.

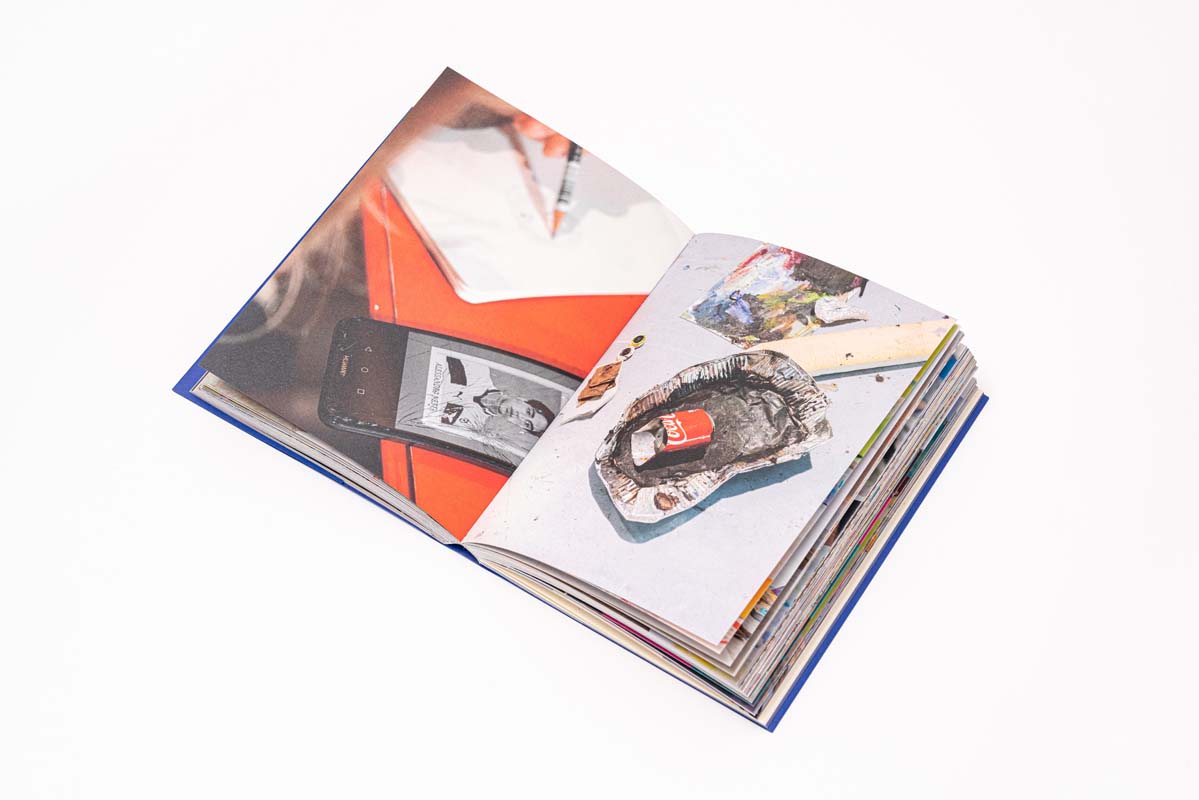

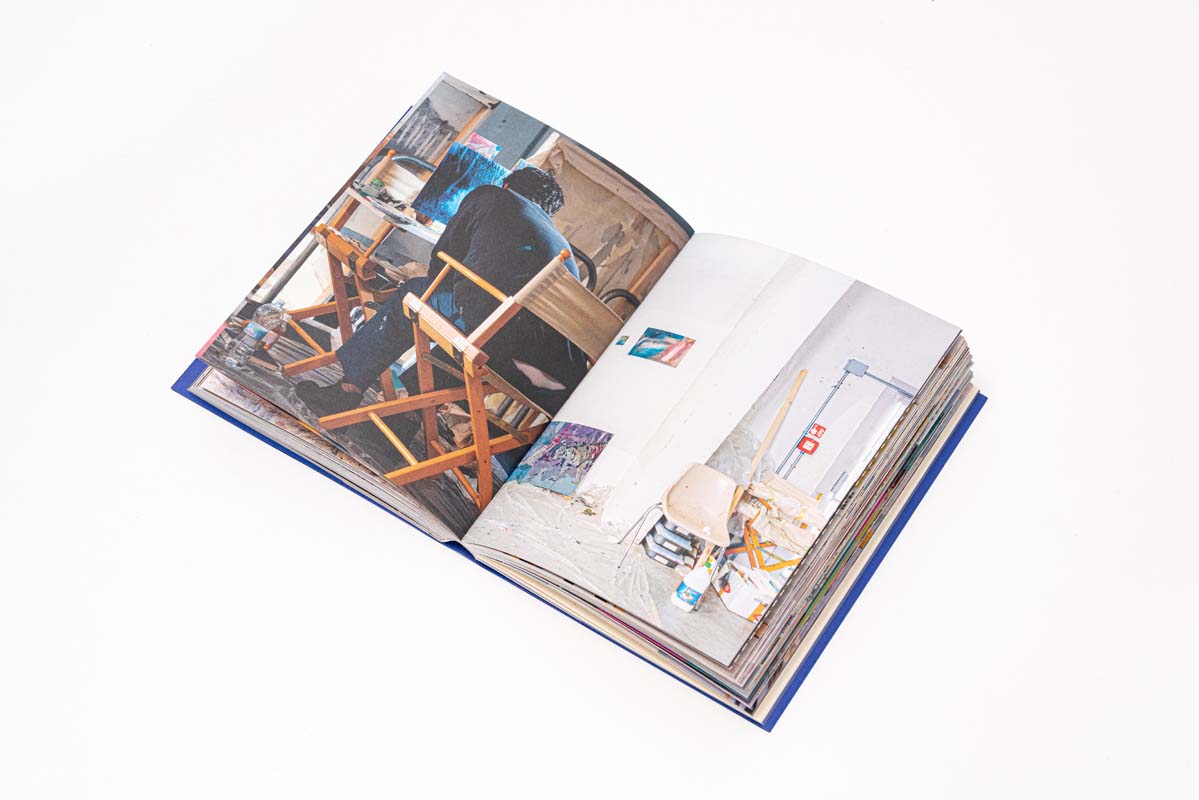

PP: I felt that during the workshop the people at Vulcano were very interested in understanding the framework within which the artists at Atelier F usually operate. All the more so, because for the artists this was not just an exhibition, a codified event to be held, but rather a real place of transformation, relationship and production, with works that appeared, disappeared or changed gradually while they were made. I don’t think it’s easy to enter the mind-set of a place where a crowd of crazy painters are at work!

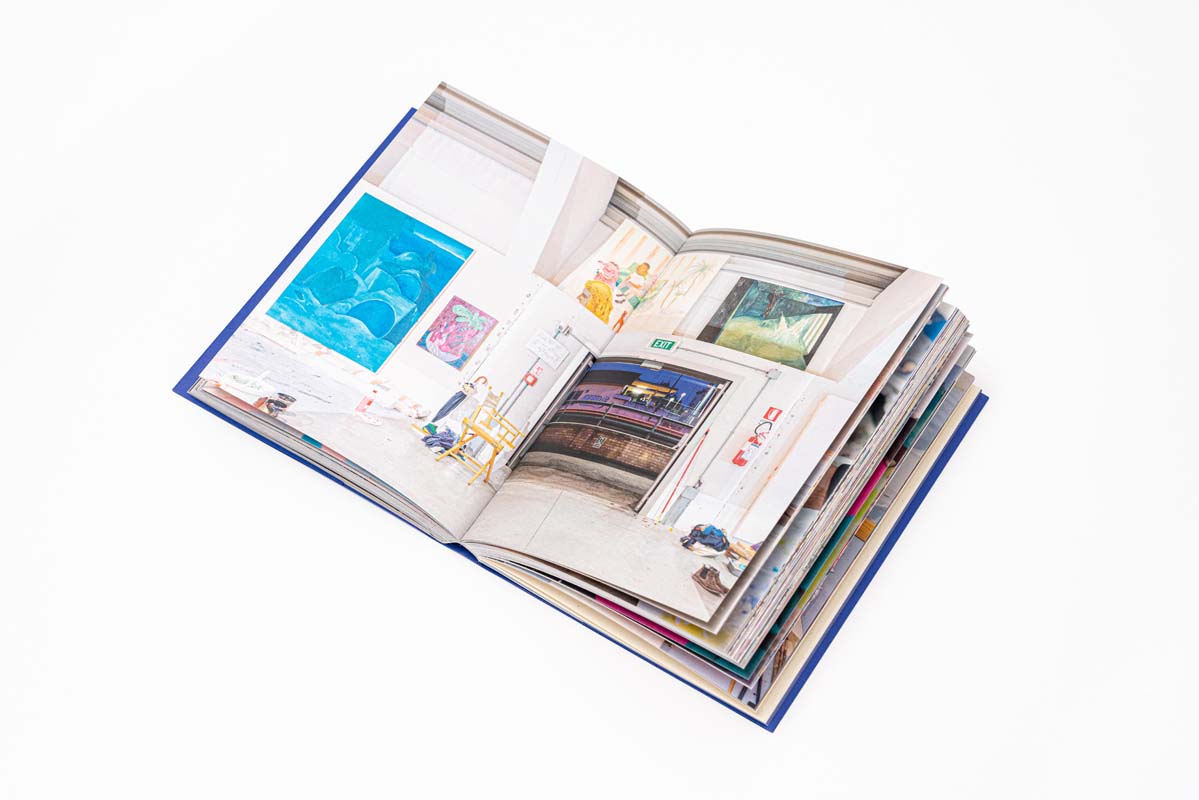

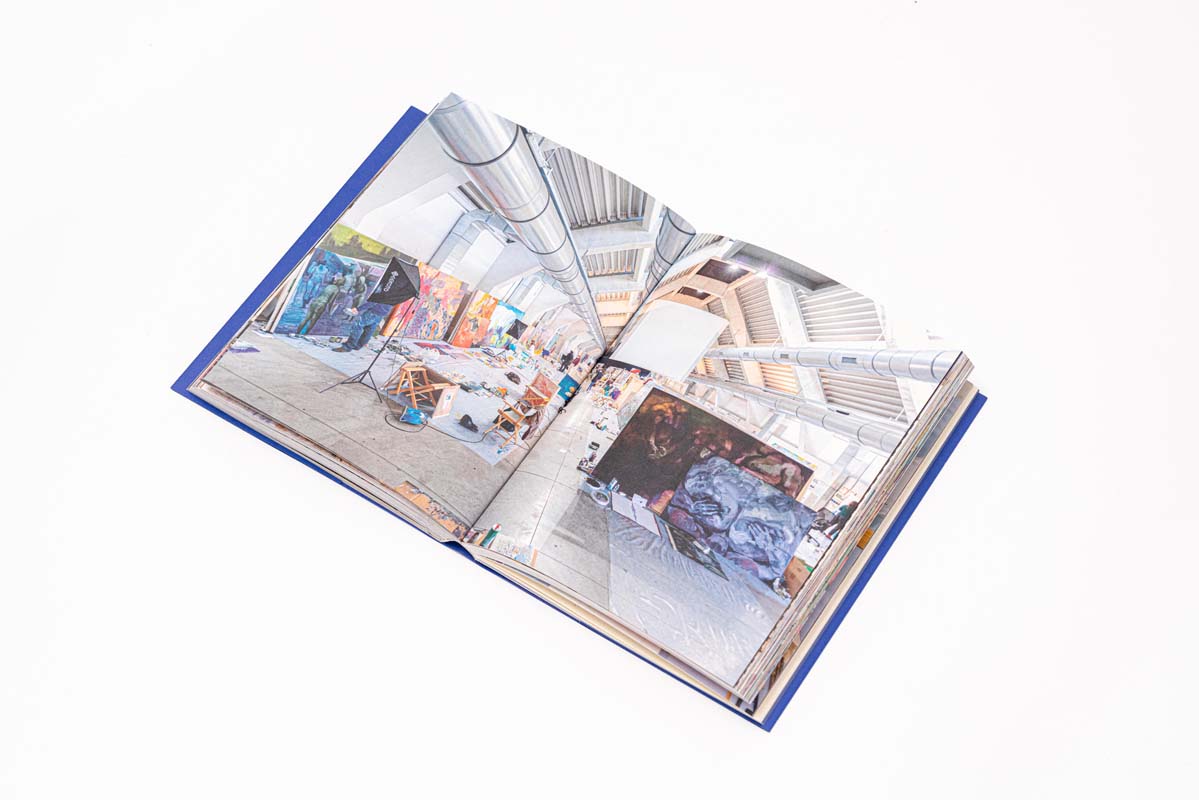

DC: I imagine that in the huge space of the Antares building many of the visitors, including those from Vulcano, were bewildered by the enormous variety of styles, approaches and visual processes. I think everyone was struck by that huge mosaic of colours. The pavilion become a genuine cathedral of painting, where a great range of research and innumerable visual languages were coexisting.

PP: That said, experimentation is a key factor. The workshop is essentially a training ground. A classroom…

DC: But, in my opinion, Atelier F is not really a school of painting, at least not in the traditional sense of being an affiliation based on a particular style or shared expressive choices. I never had the impression that the artists’ research was based on linguistic similarities or identifying a model to follow based on a specific teacher. I found that artists were adopting different visual models, and were also using different processes to construct the image. There was perhaps a similar methodology, in terms of drawing and preparatory works, which were done in a way that has something of the spirit of a visual diary.

PP: I think that in Atelier F we always started from what everyone needed most, from the personal interests of each one of us. I do not think that there was a set method, such as “use this colour” or “paint only on paper” or anything like that. And this question of the materials is clearly reflected in the most intimate expressive aspects and in the operating methods used to undertake the work.

DC: During a visit to Extra Ordinario, the director of the Accademia di Belle Arti Riccardo Caldura highlighted prof. Di Raco’s great work in listening to the students, in a didactic operation that was essentially made to measure…

CDR: The goal is to enhance the individual development, to find a personal direction to creating the image, to understand and also negotiate what the image itself suggests to the artist as it develops, through a consideration of the world and other pre-existing images. In other words, the aim is to train artists by stimulating them to experience the greatest variety of outcomes, in a plurality of languages and poetics. The teaching, in essence, coincides with the artistic production. And then through our gaze we all contribute to verifying this process. As such, Atelier F is in some ways a school of painting, in terms of the working method, which enhances the whole consisting of everyone’s work, as if it were a single organism that continually regenerates itself.

PP: It is a system that works thanks to everyone’s work. There are no pre-established formulas or models to learn, but there are lots of people next to you that you can learn from. Not learning from the top down, but side by side. This allows you to grow faster, avoiding making too many mistakes and dealing with any doubts before hand.

DC: Do you mean that there is an essentially horizontal exchange of experiences between colleagues, with respect to learning processes?

PP: Somehow yes. It has to be said that you do not learn from someone else because something is explained to you, but because you can see it being put into practice in their work. If you pay careful attention to the work of others, you actually benefit by observing how the work is done. I don’t want to sound rhetorical, but you can learn something not only from the right or wrong decisions you make yourself, but also from the decisions of your colleagues working alongside you. This process multiplies and expands the possibilities of increasing your own wealth of experiences.

DC: Some of the artists have talked about the way the tight dynamics of a workshop like Extra Ordinario help you grow as much in a few weeks as you do in a year at the Accademia. The accelerated and intensive dynamics of the workshop help the artists run faster also thanks to the legs of their colleagues. At any time you need, you are always able to ask for an opinion about the work you are doing or the uncertainties that you may be experiencing at that moment…

PP: The question of exchange, however, is much more complex than you might imagine, because it is a dialogue that is generated with much broader timing and methods than those we find simply in the workplace. Often it is a dialogue that is also generated thanks to Venice. It is a city where it is difficult not to talk about your work, even after you have closed the door of the studio, changed your trousers and you no longer smell of paint. Even in informal situations, like at the bar or eating some pasta together. We never have the feeling of completely leaving the studio, because the worlds of work and life coincide. But in the end this allows for a continuous sharing of poetics…

DC: Which is ultimately why you are all there together to discuss things. What is painting? How is an artwork structured? What stimuli lead to its creation? Which languages are most suited to my personal poetics? How does it interact with the artist and then with the environment? Or how useful is it to support or oppose its strength and communicative power?

CDR: These are questions which we never stop asking ourselves. Painting is not simply completing a project whose results are already known, but rather an evolving process that is largely unknown to its creator. It is only through a process of experimentation that painting becomes stratified into a work that is no longer subject to modification. Sharing between artists thus serves to discover a deeper level of our sincerity.

DC: It seems to me that in this process of progressive unveiling, both mature and established artists already working in the art system and the young people who have just joined the atelier share an equal footing. It seems they enjoy the same freedom of speech or criticism and the same right to be heard. Moreover, they are also given the same weight in the final set-up of an exhibition.

PP: I think that, to all intents and purposes, there is a “Venetian School”, active in our art system, despite all its atypical character and contradictions about being a school. Even the final display of the works is in some way a testament to this. Almost a hundred different sensibilities are brought into a dialogue through a visual system of relationships that is clean, but far from simple.

DC: I was amazed by the care given to setting up the exhibition, working till late at night for three days in a row. Rather than just being a context for showing the works, aimed at the outside, I had the impression that there was a didactic aim, that it was addressing those inside. Among other things, I was amazed by the fact that you built a sort of dividing wall between different areas by assembling paintings of the same size. You created “pictorial” architecture within a piece of genuine architecture.

PP: We felt it was essential to arrange the works in relation to the legibility of the space, reconstructing the process that had generated them, leaving the brushes, supports and paints visible to the visitors. But at the same time, the set-up forces the artists to have to make choices, to read what has been produced in relation to the others. It is also an opportunity to perceive some immediate or future consequence in your work.

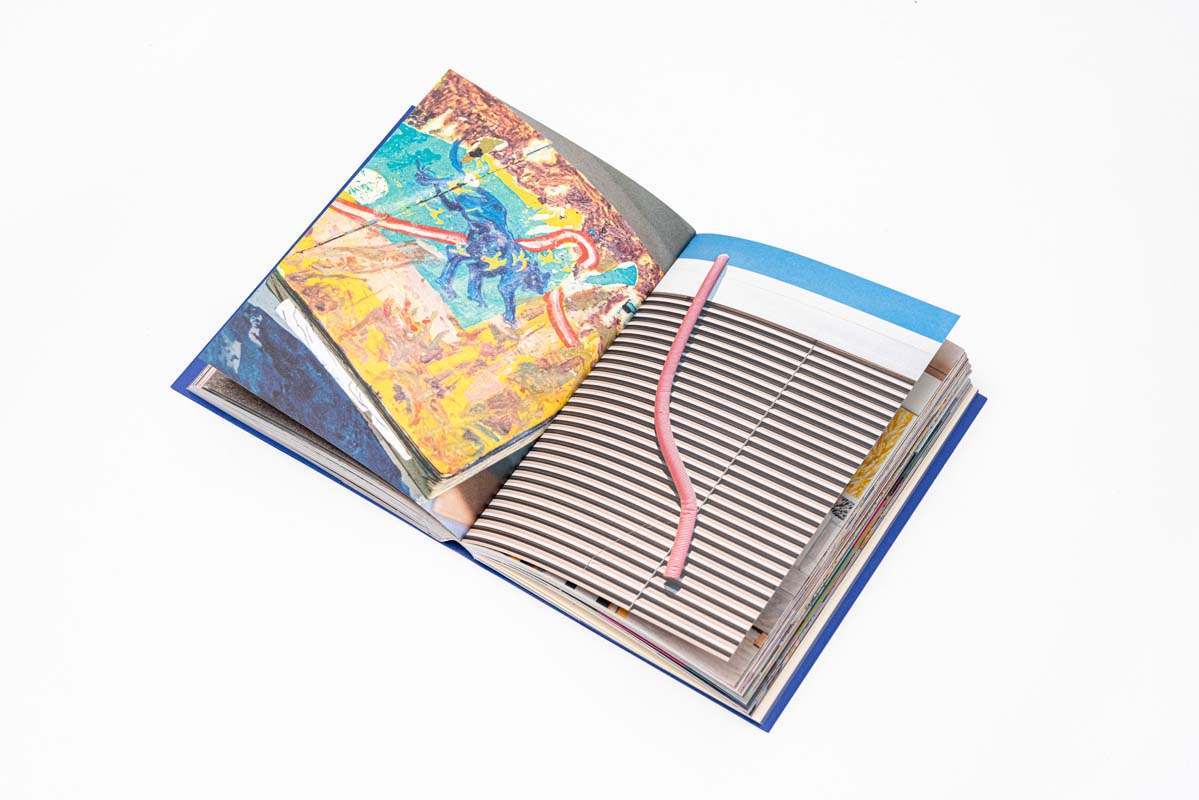

CDR: The final arrangement of the exhibition also came from the need to highlight all the contributions by the young artists. It makes it possible to understand how some works are brought into a dialogue, while the impact of others needs to be investigated later. In this way we discovered new relationships, revealing hidden perspectives or previously invisible contrasts. We felt very in tune with Nico Covre, and we were happy that his documentary and artistic work went precisely in this direction of researching and revealing the differences and similarities.

DC: I think Covre felt free to give an anti-academic reading of the visual relationships, mixing imagery and images. Not only in the relationship between the paintings and the papers in the final exhibition, but also with respect to their physical location in the Antares building, and to the narration of the events of the Atelier F workshop. In the end what is Atelier F? A group of people with the same experiences? A partnership, based on a free militancy, born from the painting course at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice? An informal, ideologically aware collective?

CDR: Atelier F is a form of artistic life based on a sharing of ways and relationships that goes beyond the strictly defined role of academic structures. There is an exchange that takes place constantly. Not only due to the presence of the works that are created, but also because of the presence of the more experienced artists, with whom we can share contexts, thinking, imagery or experiences that allow everyone to get further into their work. This is also the result of the shared effort, made by myself and these young people for more than twenty-seven years, to create a learning model that is not conditioned from the outside and seeks to give an active role to the young people involved. This has also been made possible thanks to the support from my colleagues such as Martino Scavezzon, Aldo Grazzi, Miriam Pertegato, and the artists of the atelier such as Nebojša Despotović, Jaša Mrevlje, Thomas Braida and Nemanja Cvijanović, who over time have become intellectual, political and poetic points of reference for us all.

DC: A kind of bedrock that is perhaps also the collective memory of Atelier F…

CDR: In general, the presence of an important artist and of significant artworks, pushes us to engage with each other even more, to try and get to the heart of things, moving past the surface and codified processes. I still remember the speech by Nebojša Despotović a few years ago at the end of one of the workshops in Forte Marghera. Nebojša said that what had been achieved by Atelier F was not a simple expressive exercise, but an action that was profoundly to do with the truth. Something so intense that it affects the reality of our own lives.

Conversation recorded in Venice Marghera, 11 March 2021.

Transcription and editing by Daniele Capra.