Filip Markiewicz

Road to Nowhere

Canepaneri, Milan (I)

December 2020 ― February 2021

Towards an unknown place

Daniele Capra

Daniele Capra

Sceptical eclecticism

Filip Markiewicz’s freedom of expression is surprising. His work seems to contradict the maxim that says “for a scholar’s strength consists in concentrating all doubt on to his special subject”.[1] The artist suffers from a sort of expressive bulimia which concerns not only the great productivity but also the choice of media used and the disciplines. Thus, his work in drawing, painting, sculpture, video, performance, theatre (as in the recent case of Antigone) or music can be seen close together in time. In other words, there are no limits or exclusions as his natural eclecticism allows him to feel at ease in any situation and any direction he moves in, all the more because, as he argued in one of our conversations, it’s essential “not to have a personal line but to wonder about the most appropriate choices to make on the chosen objective”.

Road to Nowhere gathers the artist’s recent works, ranging from painting to design and video, where topics and styles are dizzily mixed. The title, borrowed from one of the most famous Talking Heads songs, alludes ironically to the inconclusive situation of our present, which contradictorily features realism and fiction, uncertainty and predictability, and meanness and altruism. However, in this situation, the completely human desire to move, even towards an unknown destination, comes out, in search of an island to be totally imagined, that still doesn’t exist but it’s comforting to think that it does, that’s a little utopia, simple, unpretentious, and necessary to continue moving towards something.

In addition, it’s the anarchic, and perhaps post-postmodern, attempt to oppose an established, premeditated fate since, as the chorus says in the introduction to the song, “We know where we’re goin’ / But we don’t know where we’ve been”. Thus, with great irony, Markiewicz seems to oppose Lenin’s philosophical but static question “What’s to be done?” with a kinetic invitation to abandon the immobility of one’s position to move towards something, as David Byrne does incessantly in jest in the video of Road to Nowhere. Naturally, a doubt arises that having a direction to take or an aim to follow is pure illusion, a projection of our imagination or just expectations. What if all this was just make-believe, and the place we’re going to didn’t exist? Although we’ll never know, we should certainly take account of it, even more so if we’re with an eclectic, sceptical artist who, in his career, has created a work in neon displaying the words “Fake better”.

Counter-narrations

Markiewicz’s artistic practice features a sophisticated approach where sociological investigation, media analysis, disillusion and subtle political criticism alternate with a detached, bitter flavour. Mainstream symbols, pop culture iconography, hyperbolic irony, melancholic nostalgia and lucid realism follow each other unceasingly in his works, and the artist moves fluidly through them with an omnivorous approach. Versatility, of topic and style, is often condensed into shows where the spaces become well-structured visual devices, in which the visitor can have an experience with many emotional implications as surprises, confirmations and conflicting feelings. In particular, his work overall has an innate theatrical dimension which draws attention to the visual elements (the observer is always a spectator) and the skilful dose of the emotional component – all this ensures the chance of having an immersive, totalising experience. In addition, it’s important to note how Markiewicz is always invisibly on stage, although not always at the centre of the scene, like an actor who’s also director of the play being staged and who knows every psychological detail of the characters.

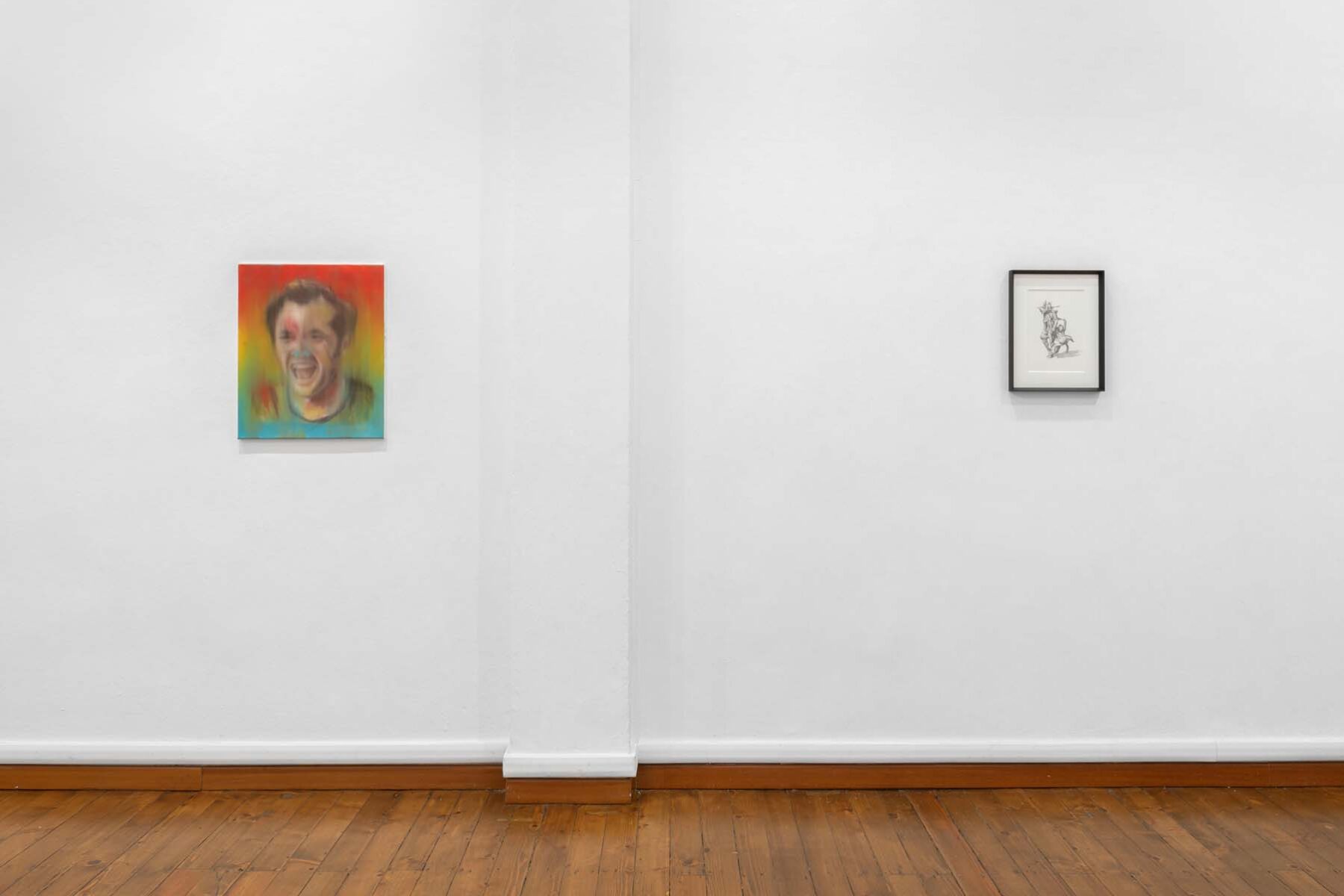

In detail, Markiewicz’s painting and his drawings are inhabited by figures that determine our fates – politically, economically, ideologically and through media. The politicians who lead the most important states, leading bankers and the CEOs of large multinational companies are players in a farce in which the artist separates their public image from the personal, institutional, political, economic or artistic credibility. Think, for example, of the oil on canvas Gerhard Nicholson, in whose title the artist blends the surname of the actor in the portrait (Jack Nicholson) with that of the artist whose technique he borrowed (Gerhard Richter). Similarly, logos briefly describing the pervasiveness of corporations and large institutions, the heroes of video games and the actors of the series are recognised in a burlesque/tragic continuum in which Markiewicz highlights the predictable and boring uniformity of the hegemonic imagination. Everything looks the same and can produce in us desire and repulsion, excitement and depression at the same time, since it is unable to scratch the surface and ontologically meaningless and worthless.

The artist reacts inevitably to the uncertainty and ambiguity of the present, in which the experience of an artwork perhaps seems one of the few escape routes or one of the few solid footholds which allow us not to remain involved. Furthermore, although we often pretend that we’re not aware of it, the contradictions, tragedies or madness we’re submerged in are a deadly quagmire that prevents us from moving freely. In Markiewicz’s practise the work itself makes visible the ambiguity and error it’s easy to fall into, and at the same time it provides an intimate and natural counter-narration about the most recurring or predictable opinion. In other words, the work assumes the psycho-analytically liberating functions of irony, criticism and ultimately the political function of dissent.

The unexpected

Our recent history, and more acutely the dramatic situation of the pandemic, has highlighted in an especially significant way how perception of events and their interactions is regulated, particularly, between two opposing and complementary types of events – what we consider “expected”, i.e. taken into account, and those that are “unexpected”, i.e. not announced. We almost perceive the former as unimportant, because it is expected, since it corresponds to established or hoped-for hypotheses. On the other hand, the latter, whose prediction is neither controllable nor planned, becomes very important because of its ability to challenge the ordinary nature of all that was previously imagined. We could say hyperbolically that only the unexpected event really happens, by virtue of its rebellion against the logic of ordinary nature – contrary to what is predictable, banal and taken for granted. And it’s because of its ability to back out of the conventional flow of our hypotheses that an unexpected event is considered as significant and inevitable bearer of meaning. The explosive energy, positive or negative, it triggers is so immense, immeasurable, that it questions our behaviour and the ways we act (individually or collectively) in the reality.

We may think about this when we observe Markiewicz’s works. Encountering one of his works is often the same as having a totally unexpected, previously unimaginable, meeting. Similar to an unexpected event, it is something that sound different and of which we are aware, not because it generates some type of instantaneous surprise, but because its reflective or iconic capacity lasts beyond the time limits of the simple contemplation of the work. Its importance clearly lies in the mental sedimentation of its content, whether this is intimate, political, aesthetical or critical. And when we got the meaning, whether silent like the boy dancing (Tanz der Stille), distorted like the body of the puppet (Dr Mario’s Dream) or reflective like the lucid words of Lech Wałęsa (Wałęsa), it doesn’t stop buzzing in our head. Just like the rhythmical song in which David Byrne walks obsessively towards a place unknown both to himself and to us.

[1] E. Canetti, Auto-da-Fé, transl. by C. V. Wedgwood, London: Pan Books, 1978, p. 60.