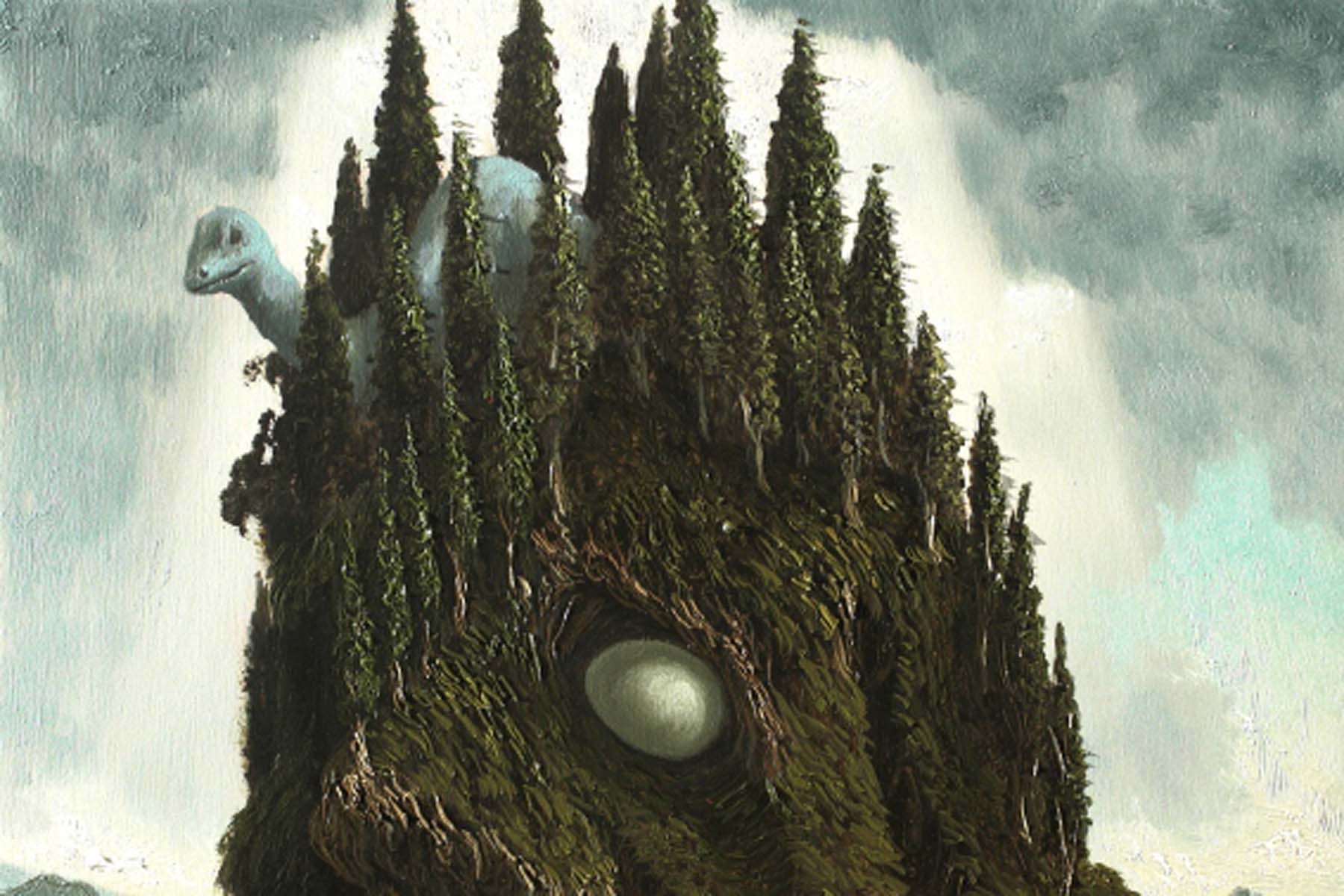

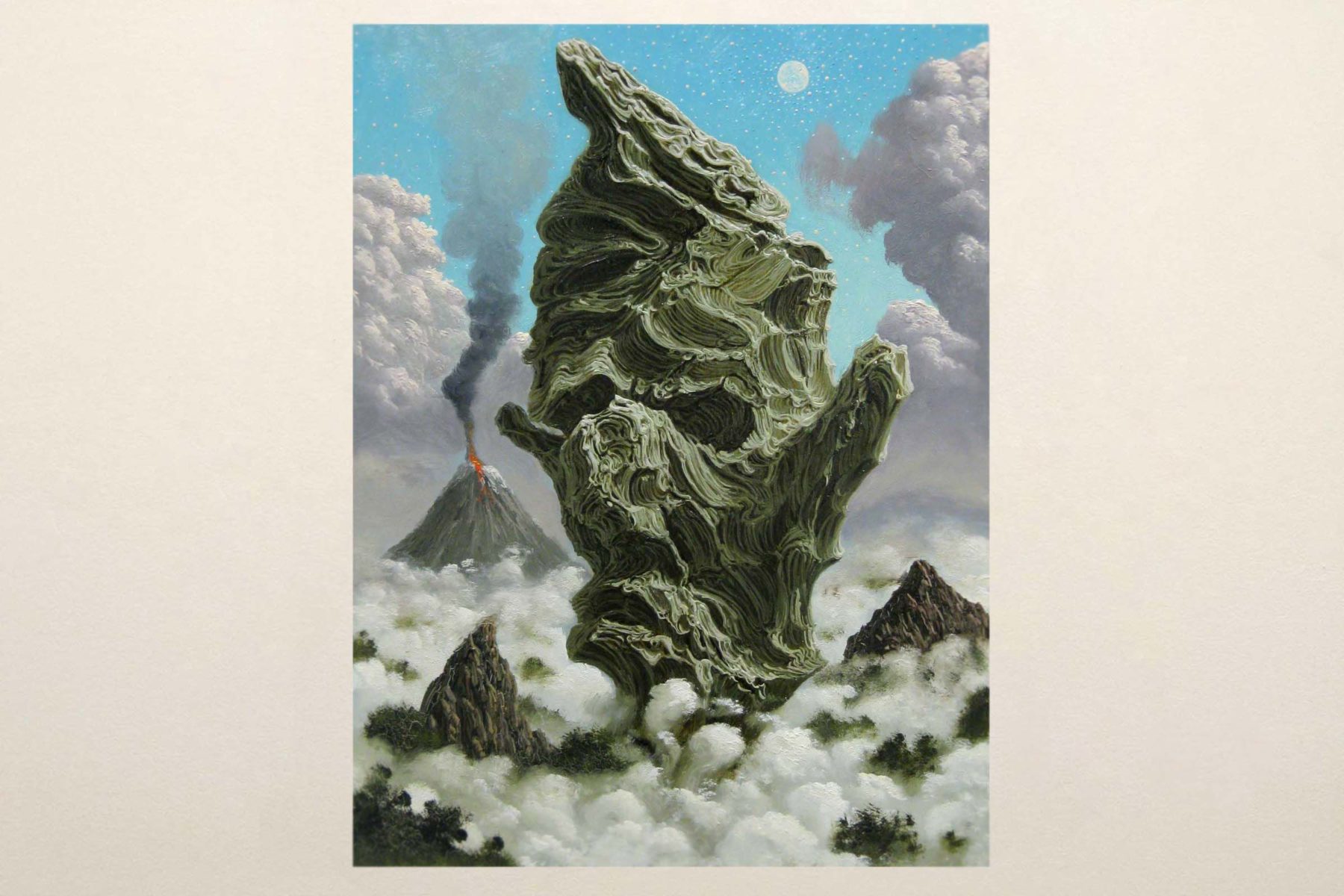

Juan Carlos Ceci, Fulvio Di Piazza

Physiology of the Landscape

Bologna (I), Zoology and Comparative Anatomy University Museum

January ― March 2011

Gastric Microcosms

Daniele Capra

Daniele Capra

To what degree has painting to do with our entrails, with our guts? To what degree is the artist’s hand driven by intellect, meant as a logical-rational control? And to what degree, instead, is it driven by the complex and inextricable organic system laying in the depths of the artist’s abdomen? [*] Even though it might appear simplistic to reduce the whole matter to the mere dualism between body and mind (i.e. between material and immaterial), a plausible and univocal answer does not seem to exist. Both elements, in fact, exert a substantial influence, which is unexpectedly less visible than one might think at first glance, all the more because they are interdependent. Indeed, it should be borne in mind that the differences between artists and the linguistic developments marking their own evolution shuffle the cards so energetically that the only way to put them in order and lay them on the table is to proceed by attempts, approximately trying to get closer and closer to their original disposition.

Physiology of the landscape is actually the result of the interaction between two artists whose painting and drawing – though characterised by very different modalities – feature visual marks and stratified sediments of organic life, which witness both to an intellectual fascination for this natural world, mostly hidden to our eyes, and to an emotional and haematic approach in which our body, thanks to its constant everyday activity, leaves clear marks of its own presence, prints which can be read on the ground. In Juan Carlos Ceci’s and Fulvio Di Piazza’s works, in fact, imaginative roots and bodily functions are recomposed to the point of coexisting, especially when they are juxtaposed in connection with a theme such as the landscape of invention, a genre which is historically far from somatic and humoural aspects, being by its very nature a fantasy exercise. The capriccio, intended both as an architectural view and as a landscape, was only acknowledged as a genre in the late 17th century (suffice it to mention the example of Giovanni Paolo Panini). Afterwards, its popularity faded away until the 20th century when its bizarre style was replaced by other approaches, always different from each other. Ceci and Di Piazza retrieve that typically baroque tendency to controlled madness, enriching it with a further element: the landscape of invention portrayed in their works often turns out to be a complex system of references, where topological aspects and animal physiology speak a similar language, since they have both been built on the fascination for the world of zoology and for that life secretly flowing in each human beings, whether animal or vegetable (indeed, in their works even the inanimate world, such as that of rocks, is often far from being untouched by the flowing of life).

The word landscape actually stirs our fantasy, evoking the tangle of natural and anthropic beauties characterising what is external to us or, very often, the most unpleasant aspects of what is around us. Yet, the landscape is not simply what we see, what lies around our houses, the place we would like to lose ourselves in, nor the endless suburbs of our own persons; it is not only the environment where we would like to be, nor the mediocre context in which our lives unwind, like in a film scenery. It is actually the result of stratifying stories and ideas, functions and projections: the outcome of an anatomical process in which many elements – such as the colour of the grass, the ground dampness, the noise of the wind, the scent of the sand – underwent changes and processes ascribable to physiologic experiences and remote psychological needs of our bodies. The two artists’ oil paintings and drawings on paper show how intense and direct, though sometimes unconscious, the relations between animal physiology and landscape can be, but also how painting can feed on apparently far, surreal, esoteric, intangible worlds. In Ceci and Di Piazza’s works the physiology of animals (and men) unavoidably becomes the measure of everything: accordingly, organs preserved in the anatomic solutions of anatomy museums, the imperious horns of stuffed animals, the monstrous skin of reptiles, the tortuous rumens of large herbivore mammals, the bright plumage of exotic birds can be recognised in their landscapes.

In virtue of its ability to create relations, correspondences, ideal microcosms, painting in particular assumes for the two artists a value of (self-)analysis, of psychoanalysis. Di Piazza and Ceci are in that lucky condition which allows them to delve into the complex tangle of emotions moving and stirring our guts, highlighting the endless and alchemical connections between our inner selves and the natural world. Although they employ different building modalities (Di Piazza has a strong passion for drawing, which is often preparatory to his works on canvas or on wood, whereas Ceci mostly paints without realising any drawing, and thus without any prearranged composition), in their works painting, with its wide-ranging dilation, proves to be an instrument which, more than anything else, can make us catch the secret and fascinating silence of everything which is other from ourselves, yet is intimately generated by ourselves: it is an instrument which links at the same time high production and discipline collecting the haematic and humoural flows of those who restlessly practise it and those who intensely see it. In the two artists’ works, it is especially the landscape – traditionally considered a sunny, apolline, limpid genre – to showcase the unbridled physiologic vitality of the lymph, of the humours, of the gastric elements which are secretly animating the existence of each human being.

Their works, thus, show to what degree painting has an endoscopic organic function, enabling us to glimpse the endless addends hiding in the abdomen of a sum whose value we irrationally realise, even though its correctness cannot be known. It is the body speaking an atavistic language, once sectioned and exhibited to those who have eyes to see. It is the scalpel allowing us to cut our own skin and search in our entrails for the inner juices, the depths, the poisons lurking in our abdomen and dwelling in the projections of our fantasies, our fears, our expectations. It is the melancholy of a world where suddenly it’s evening and which, though in all its liveliness, suddenly turns us into still lifes.

[*] The exhibition was inspired by an intense conversation which took place over one year ago between the artists, Giorgia Lucchi and the curator. On that occasion, the dichotomy between “rational painting” and “impulsive-visceral painting” had been analysed, and that debate was the prelude to the theme of the exhibition in the Bolognese museum.