Giovanni Morbin

Something Else

Rijeka (HR), MMSU Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

October ― November 2014

Daniele Capra

If the one who does not fight alone is executed, the enemy has still not won.

Bertolt Brecht [1]

Premise I

What is fascism? Why does it still, even though the 20th century is behind us, make sense to discuss its influence? Noam Chomsky, one of the most insightful intellectuals of our times, who analyzed how centers of powers and different lobbies affect “the ways of the world”, offered a Cartesian definition of fascism. Chomsky says fascism is “ideology based on domination, oppression and supremacy of one individual over another, prompted by certain reason or need, fed with false or manipulated information”.[2] Chomsky has broadened the definition of fascism from politics onto the realm of human relations and ethics: human tendency to power abuse and dominion may indeed be applied to any field of human activities, from culture to science, from economics to politics, from providing information to a behavior of an individual. Fascism is actually much more prevalent than it seems at first glance. It eludes the classifications of political and social sciences, especially with regard to its influence on the public sphere of human activity, as well as on intimate lives. Pasolini’s example can be viewed through this lens. In his soul-stirring, visionary work Salo’ o le 120 giornate di Sodoma, Pasolini describes the north of Italy occupied by the Nazi-fascists, where the immorality of four colleagues becomes a metaphor of a political mayhem destroying the country.

Contrary to the belief that Fascism as a historical phenomenon has been surpassed, it is fundamental to examine how it has evolved into a human inclination, resulting in behaviors quite different from those that were typical for its ideology in the 20th century. The examples and effects are visible in the field of economics, where extreme capitalism and uncontrollable system of finances have turned into a state religion, but it is also evident in interpersonal relations and desires of the masses, tailored according to models imposed by media and entertainment industry. Inevitably, the idea of domination has proven attractive, spreading destructively onto each sphere of human activity, proliferating like an infection, a virus, covertly crawling under people’s skin.

Premise II

Gaetano Azzariti was the prime example of how Italy dealt with fascism in the period following the World War II. Owing to the fact that he enjoyed protection of several political parties, his case and activities remained unknown to the public. After building a career as a judge in the 1930ies, Azzariti continued to work in Rome at a legal department of the Italian Ministry of Justice. As a fervent fascist, he endorsed Il Manifesto della Razza (“The Manifesto of Race”) [3] in 1938 and became the president of the Court of Race that had been established within the Ministry. He was responsible for the implementation of shameless, discriminatory norms against the Jews, in favour of the “supreme Italian race”. During the presidency of Pietro Badoglio, between 1943 and 1944, Azzariti was appointed Minister of Justice. After the World War II, Azzariti started working with Palmiro Togliatti and became the president of the Italian Constitutional Court.

In any normal country, Azzariti would have been convicted and executed for his wrongdoings right after the end of the war, or he would at least be sentenced to life in prison. However, like many others at that time, he continued to work in state institutions and represent the government. What surprises the most in this story is the fact that Italy has never done what other countries did: it has never dealt away with its fascist past. Therefore, the Republic of Italy was not born from the ashes of Fascism: there is an embers that are still burning.

Premise III

The song Somethin’ Else was first released in 1959. It was written by Eddie and Bob Cochran and Sharon Sheeley, in the rockabilly style of the time. The lyrics are probably forgotten today, but the melody is quite catchy. The single was successful, although it never reached the top spots on the hit lists. Led Zeppelin’s version, written about ten years later, was much more prominent, but the version recorded by the Sex Pistols and Sid Vicious became quite a hit in 1979. The Pistols turned the single into a pure punk-style situationism. Less than six months from the release of the single, Sid Vicious died from a drug overdose in the United States, right after being discharged from prison.

The cover of the single was made by English artist and anarchist Jamie Reid, who often worked with the band. It showed Sid Vicious standing in a doorway, wearing a leather vest, a chain around his waist and a red nazi T-shirt. It became the symbol of punk: coincidence, connections to situationism, provocations and a lot of vomit in the world.

Premise IV

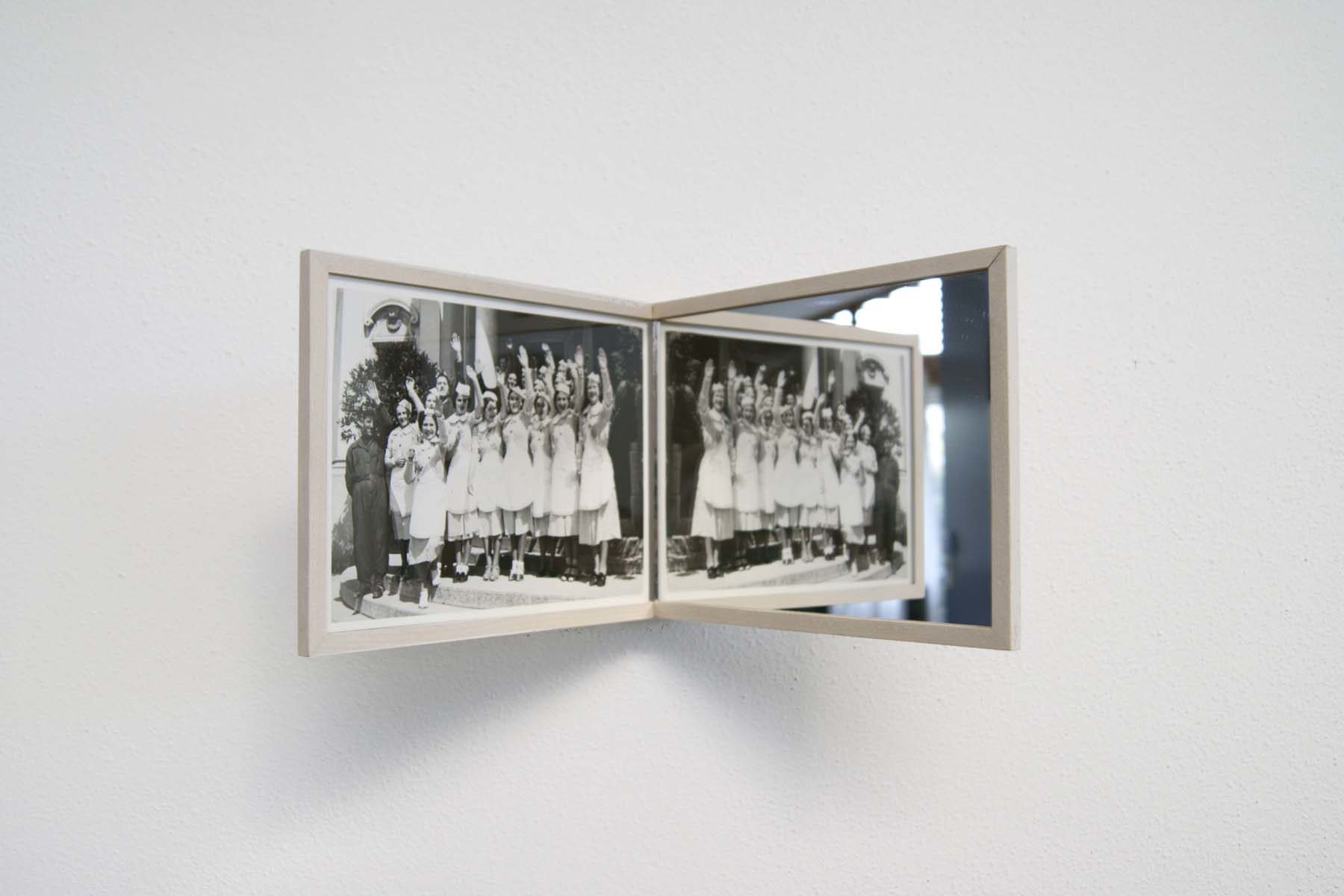

Discovery and preoccupation with the body was one of the common practices of the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century (although habits of it are different). Apart from architecture, body was the place for materialization of political ideologies, for creating a specific form: body was a functioning cog of an immense machinery.

As Boris Groys puts it: “Italian Fascism and German National Socialism adopted the artistic program of making the medium of the body the message, and they made the message a political one. They sided not with convictions, theories, and programs, but with bodies – those of athletes, fighters, and soldiers”. [4] A body of a hero-athlete or a patriot was turned into a myth, a model that served to inspire the masses to follow the spirit of the ruling regime. It was an ideology contained in blood, sweat and bravery.

Biology of an artwork

Political and processual topics, and esthetical-perceptive content are two artistic research fields often categorized into two opposing positions, both by Marxist critics and curators, who like artists dealing with political issues, and by those preferring artists working on formal research. Beacause of this sort of Manichean dualism only extreme works were acknowledged by professionals. More complex, hybrid research was being neglected giving chances to too much political and rhetorical art, or to some conceptual art that did not have a concept at all. The result was ironic and paradoxical: if we are wall-eyed, we see only the extremes, but miss what is in between.

As Giovanni Morbin’s exploration confirms: the world outside, luckily, has many more nuances than suggested by the criteria of taxonomic classifications. Morbin’s work is a combination of an attention to processuality and a relationship to form: it is a fruit of hybridization, a blend of disparate elements that create manifold layers and make his work complex, just like in biological processes. It is not a coincidence that many of his works and performances were conceived as hybrid structures, as a mechanism that produces effects that surpass the mere sum of their sources. Since the word hybridization contains the idea of action, hybrid artwork is not immovable and closed. On the contrary, it is able to provoke a reaction in the observer, by putting them in an awkward or dangerous position.

Morbin’s work is not a decorative plant in spring blossom, impressed by its own beauty, but a thorny hedge in a passage, ready to prick and scratch those pay no heed, regardless of whether they water it or not. Morbin’s work warns us what will happen of we divert our attention, lose concentration, don’t perform any action, or think, for instance, about the dangers of Forza Nuova (“New Force”) or L’angolo del salute (“The Heil Angle).

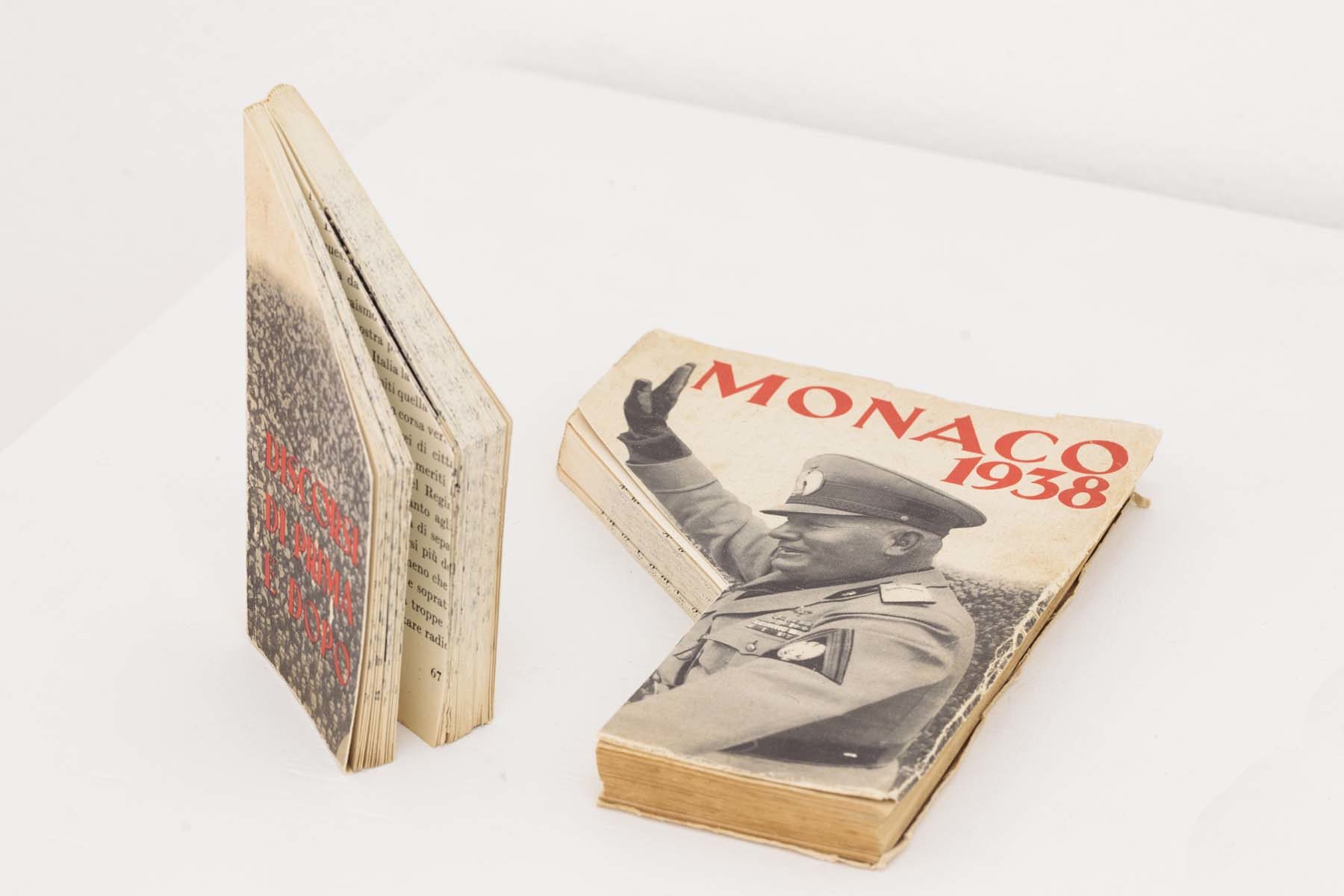

Anti-rhetorical (anti)fascist Morbin’s

Fioriera (“Flower Vase”) is made of steel, in the shape of a swastika, designed to be functional. The horizontal parts of the vase contain decorative flowers (ivy and forget-me-not,[5] for example). The work provoked a scandal during the exhibition at Artissima Art Fair in Turin, where a Jewish gallery director accused him of being nazi-nostalgic. Forza Nuova is a very active and militant left-wing political party inspired by Neofascism. However, Morbin’s brass sculpture in the shape of a projectile coming out of a wall is also very dangerous. Me is a performance act in which the artist spins on a chair, trying to declaim Mussolini’s speech from June 1940, in which he called for war. Morbin keeps spinning, looking like a futuristic sculpture, until he manages to get off the chair and runs to the wall where he writes a big M (standing for Mussolini, and, intimately, Morbin), followed by a small e, which finally makes the word Me. L’angolo del saluto consists of a series of works (collage and sculpture), conceived upon the image of the fascist salute with outstretched right arm. The author repeated the idea in another performance act that was presented in Rijeka – D’Annunzio’s Fiume – where he wore a cast, thereby forced to hold his arm up in the air. The series refers to politically reactive systems and Fascism, to which the artists does not resist in a direct and visible manner. By avoiding clarity and didacticism, i.e., by refusing to show us a direction to follow and thereby hiding his own position, Morbin continues to displace us, in order to make us question our own political attitudes. In other words, Morbin provokes a persistent ideological displacement (similar to the Dada practice of changing the contexts of subjects). This way the viewers are not served with the old “morality soup” that highlights the otherness or proves the righteousness of an anti-fascist. On the contrary, it confronts the viewers with uncertainty, makes them doubt his political inclinations, without any moral suasion. The viewers are thus forced to express their opinion, their agreement or disagreement. The origin of such anti-dogmatic attitudes should be sought in a love for deconstruction, typical for the 1970ies punk. Deconstruction was in opposition with an ideological rigidness of the time. What was also observable was auto-censorship, as well as connections to anarchism of the Situationists, protesting against the stern attitudes imposed by Debord’s society of the spectacle.[6]

Body, metaphor, behavior

L’angolo del saluto derives from contemplation on the volume of air formed in the salute that the fascists used since the 1920ies. It is an unconscious modernist sculpture and, at the same time, a mise en scène for audience. It could be seen as a formalization of gesture that is clearly visible from a distance (in contrast to a handshake, for example). In the open volume of the Salute we can recognize a sculpture of infinite dimensions, which does not contain anything but a physical emptiness: it is a trap set by our own bodies when a common action, a simple ritual devoid of idea, transforms into work. Belvedere consists of two pieces, a hand-made and custom- made male leather shoe and a box. The heel of the shoe is quite taller than usual, and contains a metal part that keeps the shoe in the horizontal position. The work is obviously a metaphor of a desire for control (which is guaranteed by the elevated position), of a pursuit for superiority. However, it is also an ironic criticism against the übermensch, and the desire to walk ten centimeters above the others. Finally, it is an egalitarian or maybe even anarchistic criticism of domination and of the use of body. A criticism of grim power that oppresses both the puppeteer and his puppets.

Beauty will not save us, nor it will save the world. In the meantime, let’s remain on guard.

[1] Auf den Tod eines Kämpfers für den Frieden, in Bertolt Brecht, Svendborger Gedichte.

[2] See Noam Chomsky, Understanding Power, New Press, 2002.

[3] Il Manifesto della Razza was a shameful racist manifesto signed by scientists, university researchers and intellectuals in the Agoust of 1938.

[4] Groys, Boris, Art Power, MIT Press, 2008, p.131.

[5] Forget-me-not (lat. myosotis) has the same name in many languages of the Indo-European origin: «ne m’oubliez pas» in French, «nomeolvides» in Spanish, «vergissmeinnicht» in German. The artist selected this particular flower for expressing the ironic connotation of Nazism.

[6] The Society of Spectacle bt Guy Debord was published in 1967. The essay became one reference book for the members of the Situationist International.

Against the atrophy of our critical faculties. A conversation with Cesare Pietroiusti

Daniele Capra

A few years ago you invited Giovanni Morbin to the Swiss Institute in Rome to present a performance. What was it that struck you about his work?

What struck me was the fact that an artist like him – someone who is a deep thinker, with a well developed approach and a long history of on-going research – was in some way excluded from the principal art circuits. I was curious about this discrepancy between a mature artist and the fact that he was in some way on the periphery of the contemporary art system.

You mean his lateral position…

There was a significant difference between how well his work was known and the depth of meaning of his artwork. But the opportunity also came from a collaboration with Maria Rosa Sossai, with whom I had been discussing the idea of self-censorship and the attempt to overcome it. Perhaps it is precisely the fact that this work was born from fascism that led to it being interpreted by Maria Rosa as an attempt to reveal the dark areas and behaviours which relate to our past as Italians, and also to our contemporary psychological and anthropological interior nature. I think that for Giovanni – and also for a number of my artworks – the interest in fascism is not just in terms of a phenomenon of the past, but it is also an attempt to reveal the present, the dark areas that our part of our personal history and our psyche. Even if the records show that we were born and lived after the end of fascism as an historical event.

I also interpreted the performance Me as an attempt to eviscerate fascism as an existential condition. Even though they were not all politically fascists, I think that all Italians were fascists in an internal way, making fascism acceptable in cultural and human terms. That is the reason we have never been free of fascism and we have never thrown out this looming father…

I’m even more pessimistic. I don’t think it’s a Freudian issue and the disturbing return of a father figure, and nor is it an issue which belongs to the political sphere, where it is possible to purge – even aggressively – some of the toxic elements. To my mind the central issue is that fascism from our century turns a spotlight on characteristics and values which, anthropologically, we all carry around inside us. For example, you only need to think of what Fabio Mauri revealed about cult and the worship of beauty: fascism took full advantage of this kind of rhetoric for its propaganda. This is exactly the same as what happens in the entertainment industry,[*] in a pervasive, insidious and subtle way. In regard to this aspect, there are no fathers to be killed: everybody is involved. The way I look at it, Giovanni’s work is not ashamed to show precisely these aspects, which are normally part of our defence mechanisms and self-censorship. It does not oppose the rhetoric of saying “not me” to an internal fascism that we fool ourselves into thinking we oppose, without realising that it is actually within us.

But don’t you think that fascism had a skill for appropriating any kind of element or symbol? For example, in his speeches Mussolini said that “a sunny day” was “a fascist day”…

This is something Fabio Mauri often spoke about. He was born in 1924 and, like all children at the time, he was in the Balilla (Italian fascist youth)- indeed, he actually met Pasolini at one of the meetings for young fascists. Mauri spoke about how hard it was to accept the defeat in the war, and the human and moral catastrophe which followed, when in everybody’s mind “even the sun was fascist”.

Fascism was in some way a kind of natural situation that they were insidiously inserted into from the moment they went to school onwards. I think that Morbin’s research contains an attempt to overcome precisely this kind of conformism, which we saw in historical fascism. But there are also successive fascisms, in the sense of meta-historical categories…

Giovanni’s work is one of criticism, I’d say along the lines of the philosopher Adorno. It is a work that reveals the mechanisms, but does not offer solutions for a happy ending. It is a work that bitterly underlines impossibility and demonstrates the weight of this, something we would prefer not to listen to. In actual fact, the thinking goes beyond fascism itself, and may refer to any aspect that we would rather not see. I’m reminded of the performance Body Building, where he stayed for hours with his hand cemented into a building. The work is deliberately uncomfortable. A punch in the stomach for the desire to react, maybe to act heroically, at least to do something. It is a work that documents impossibility, which bitterly reveals impotence, but at the same time it seeks the freedom from the shameful tendency to act happy and deny any form of difficulty, which society expects from its individuals. In this way, this artwork is an attempt to oppose meta-historical fascisms.

In line with this intention to produce an uncomfortable and heavy artwork, I am reminded of the swastika-shaped flower stand. That artwork underlined the attempt to re-appropriate a symbol whose origin goes far beyond its use by the Nazis. Perhaps it also sought to bypass the monopoly over memory and tragedy that seems to belong only to the Jews, almost as if this negative symbol only represented an offended party. I find it very interesting that Morbin makes the viewer doubt the thinking of the artist…

This artwork, Fioriera, had a strange effect, because the combination of a symbol which we identify as a sign of absolute evil and the presence of seemingly innocent flowers throws an incredible shadow of horror over the flowers. It is an image I find disturbing because it turns something cheerful like a flower, that we normally find in nice middle-class houses, into something disquieting. As such it seems to me to be a work that talks of the normality of appearance, of the “banality of evil” that is hidden inside so many symbols, as Hannah Arendt said. And yet this same, apparently normal, society is capable of creating monsters, a horror story. I have a background in psychiatry, so my reading of this it is a symbol that hides the horror of domestic pathologies, such as psychoses, discomfort and addiction. I love flowers, but I can perceive a treacherous use, a decorative domestication which stinks of fiction, of hiding.

Also Belvedere – a man’s shoe with an oversize heel, which is nonetheless able to stay upright thanks to a hidden counterweight – seems to reveal a psychotic attempt by someone. But in this case it is an attempt to feel superior to others, to rise above the masses.

In psychoanalytical terms I can also see an analogy between this work and L’Angolo del saluto, because I can see a reference in both works to the idea of erections and to the typically male obsession with having to act. They both seem to allude to a virile obsession towards a kind of permanent priapism, a continual and ostentatious erection. They clearly remind us of the position of an erect penis and the male obsession with predominance. Also, in both artworks, there is a desire for elevation, almost to construct an architecture that opposes gravity.

L’angolo del saluto is also based on the idea that the angle of a person’s arm is a standard position, which makes the gesture visible and recognisable even from a distance.

It is clearly an easy position- ergonomic, almost instinctive. It reminds me of Leni Riefenstahl’s film Triumph of the Will, and the way that as the Nazi leaders passed by the people along the side of the streets automatically saluted with their arm sharply raised, as if the people were prey to a kind of collective phallic excitation.

There is clearly a choral element here: everyone makes the same gesture together, affirming their belonging. We are not considering whether the salute was also the same in more intimate or personal situations.

There is also a recognition of authority in public situations. When Mussolini was there everyone saluted, raising their arms towards him, and he returned the salute to the masses. It would be interesting to make a study of private occasions, although I imagine it could now only be conjecture. It might be interesting to investigate whether the fascist salute was also done in the mirror, in a narcissistic way, relishing the vision of oneself as powerful.

I believe that both L’angolo del saluto che and Forza Nuova are futurist sculptures, in that there is a tension towards movement. But beyond this, both works also have a great offensive potential towards the viewer. In the first there is a sharp steel blade, in the second an almost invisible bullet placed at eye-level. What do you think about this offensive potential, which emerges if the viewer, or possible purchaser, is not paying attention?

In Morbin’s work there is often an attempt to make thoughts into something material, or into corporeal experiences, both through ideology and language by using known phrases or striking solutions. Beyond the obvious reference to fascism and danger, I can see a reference to minimalist sculpture and the attention to form and geometry. It is as if it was a warning against considering sculpture as a comfortable and pleasant fetish, to be exhibited or flaunted. I think that, in general, all minimalist sculpture is very sharp and aggressive, because it does not consider the viewer as part of the artwork, but rather opposes him with the very volume of the sculpture itself, physically removing him from space. The sculpture of Michael Heizer, Richard Serra and Donald Judd, particularly in their early years, tended towards an overwhelming gigantism. In Giovanni’s work I can perceive a desire to work with the space and instead create imaginary volumes.

With gestures and structures that are delicate and slight…

Yes. I remember a visit to the Dia Art Foundation, in Beacon, outside New York. There were all these enormous, massive, gigantic artworks, and then there was the work of Fred Sandback, who was creating forms simply by using a few stretched threads. Sandback managed to get the viewer to perceive the volume, the mass, without needing to have the heaviness of the material. As such, his structures were not oppressive, because there was a lot of space left which could be used by human beings.

What do you think about a sculpture that is minimal, but not minimalist, like the button that Giovanni made to be worn on clothing and carried around?

There is obviously a sense of irony towards the preciousness of the art object in the fact that you can carry it around with you, rather than display it in a dedicated space or in an exhibition context (which unmasks the rhetoric of showing/seeing). However, at the same time, it is a reflection on the things in our everyday lives that we do not pay attention to. Made precious by the material, the button is an emblem of a small thing that requires a great effort of attention.

Also because you risk loosing it!

A risk that precious objects do not normally run, as you don’t normally carry them around with you, but rather keep them in a place which we psychologically believe to be safe.

I don’t know if Morbin would agree with my reading, but the button-sculpture is also an ironic artwork in relation to the role of the artist, to that which society and the system require him to produce. It may be more expensive, but in the end the button has the same function as any other that can be bought in a haberdashery…

That is true if you interpret the figure of the artist as one who produces precious objects. But I suspect that it is precisely irony that puts him in the position to be one who creates meta-precious objects. I think that both Morbin and I interpret the work of an artist as an attempt to overcome the dynamics that create the mental automatism and conditioning which lead to the atrophy of our critical faculties. I think I find more ironic the performance Attacco bottone con tutti, which seems to be more of a parody of relational art and the ideology behind it- that is the idea of making art that involves everybody at any cost. It is clearly a very subtle irony directed at artists who seek an audience in any way they can think of, me included.

[*] In the original Italian interview Cesare Pietroiusti refers both to entertainment industry and Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle.

Daniele Capra

Why did you become an artist?

After a series of failures in the course of my education, an art school that gave me self-confidence set the path for my further studies. By some miracle, everything that had been bad unexpectedly turned into something good. All my flaws were suddenly considered as something precious, my distinctiveness was studied, nurtured and developed. Thoughts and processes that had once seemed meaningless became a necessity. It was then that I finally began to feel like being a part of something. Oddities found their meaning; restlessness became the source of expression. So, this is when I decided to become an artist.

Was it important to continue along the winding path and create a language that could be applied in the future attempts?

To be honest, I was not aware of my attempts. Contrary to what I had expected, I often ended up in an environment that I perceived as hostile. I knew then for certain that I was at a wrong place. On the other hand, artistic environment offered serenity: I could play and discover that others had been there, too. Such a wonderful revelation!

In what way has your exploration changed from its beginnings?

My first works had a militant tone. I searched for formal solutions, supporting the position of art. My current work mostly expresses a personal attitude towards the world; it takes a direct responsibility. In the past, I used to devote a lot of effort to gain experience, to test my own limits. But now I am mostly interested in situations that include other people. I try to offer ideas that can be exploited, used as tools.

How can a form have a militant tone?

A form has a militant tone when it expresses a content that does not care if someone agrees with it or not; it is militant if it pursues its intentions or ultimate goals, despite the possibility of being rejected in the end. I was interested in the extraordinary, in the uncommon. I wanted to “shuffle the cards” and call the acquired skills into question. I was never concerned with attracting the interest of people from my profession, in being the master of my trade. I always thought that each author is responsible for taking responsibility. I am simply telling you what I feel, I do not want to quote other authors and other works, since there are numerous references I could cite. However, there is one name I have to mention: Giorgio Fabbris, the artist who saved my life in a way.

What does the notion of form mean to you? What does it refer to? Don’t you think that, especially in works based on reinterpretations of something that is behind us (history, ideologies, actions of individuals), a form is only a tentative and momentary appearance of a real, internal process?

Yes, I agree. But what is also true is that the form is the first thing that attracts you, it calls for your attention, and you don’t move on without having learned something. A form is a suit that you put on a body. If the body is missing, that does not mean there is an anti-form, but there is a fashion…

If you look back, do you still recognize yourself in all the forms you have created?

I am not an extremely productive artist and when I release my work and make it public, I simply believe it is the right moment for releasing an idea that obtained its clarity through form. Speaking of my work from this point, I have to say that there aren’t many things that I would change. Of course, I do detach myself from the past, to some extent, and if I had to create some of the works all over again, I would make certain adjustments. However, there is always a consistency between what I am and what I do. I did not name one of my works The Forms of Behaviour without a reason…

Do you think that your works contain repeating topics, motives and characteristics?

Of course they do! For instance, many of my works explore the meaning and importance of hand as a tool. My other works investigate the relationship between work and its possessor, even to the extent of turning a collector into a participant, making him or her responsible in the process of creation. In performance acts, I search for non-spectacular options that draw attention to something that misses the eye, to something that we think it’s not there. The seeming non-existence of a work of art, the lack of possibility to see it as a product of artistic efforts, is something that I am really interested in. It would be wrong to say, for example, that the evolution of species has never happened, just because the process takes time and it does not happen before our very eyes.

How did you become interested in performance?

I had a classical training in painting. However, I had teachers who discussed all this, both from the outside and the inside point of view. While I was developing as an artist, I was surrounded by discussions about what object is (or is not), discussions about traditional art and alternative strategies. That was the moment when I decided to stop painting. What remained was a strong need for expression so I was exploring the ways to make the expression effective. I started to work with my leg in order to confirm that I do not produce art: in Italian, a saying that something is done with your leg means that something is done poorly, clumsily – Boccioni’s and punk style at the same time. In relation to that, I focused on the body and its behavior. I have to admit that leaving the world of painting was inevitable in my case. I felt like a soccer player who is faster than the ball. Painting was simply too slow for me. I was searching for ready-made answers, sudden transformations; therefore, artistic action was the perfect medium for expressing my endeavors.

Have you ever though that you should have done things differently?

Yes, maybe I could have gone deeper into things. Nevertheless, everyone gives answers in accordance with their nature.

Do you have any experiences or works that you see as mistakes?

Yes, there are some works that I would not repeat, but they happened for a reason. Today they probably wouldn’t leave my studio, but I wouldn’t destroy them.

Would you tell us about the unusual performance in which you went “not to see” an exhibition?

In April 1987, Vivita gallery from Florence organized an exhibition of Duchamp’s works. Duchamp was the artist who helped me open my eyes. After a long studying of his work, I was quite intrigued and heavily influenced by Duchamp as a man and an artist. So I decided to go to Florence with a firm intention of entering the gallery, but not viewing the exhibition; it was a genuine and honest act of abandoning the visible. Duchamp was never interested in the visible. Moreover, his writings containing the explanations of his works were always (and still are) so hermetic. So what was the point in showing his works? What was the point in seeing the exhibition? I decided to take this trip with a friend of mine, Mauro Roncolato, who knew little about the artist and art in general, so I could identify myself with him. I travelled blindfolded, and Mauro was helping me manage all the way. We arrived to Bologna first and came right in the middle of a railway workers’ strike, so we had to get off the train and take the bus to Florence. Since there were not enough buses for all of the railway passengers, we were not sure if we would make it to our destination. However, noticing my “defect”, people gave us the priority to get on the bus. We finally came to Florence and entered the gallery. Mauro started to describe the exhibition for me, while the gallery personnel were looking at us with curious expressions on their faces. After that we went to the post office to send a postcard saying: THE EXHIBITION! Mauro Roncolato is showing Duchamp to Orbin Giovanni. [○]

This performance speaks about how a series of deceptions arising from the artist’s intentions influenced the functioning of artistic system. An artwork is made to be visible, but, who knows why, the viewer cannot see it, agreeing to his own blindness. What is your role here?

Well, we can miss out on things because we look in another direction. I have never expected the world to stop just to see my interventions. In my work, I simply live with the rest of the world. I perform my acts spontaneously through the day because I like accidental encounters with my work, which is also the reason why I have never wanted to go on stage. And slips and oversights that happen in the process correspond with the ideas I represent.

What is art for you? What does it have to create?

I always thought that art and artists have to talk about the time they live in, interpreting the world like no one has done before. Art and artists should talk about habits.

Is that the form of responsibility you mentioned earlier? Do you think that you have overestimated the role of an artist

I think not. I believe that an artist, in a Socrates’ sense, contributes to a distribution. Some say that they are not interested in changing the world through art. I don’t know if this is possible, but I do feel that an encounter with someone or something moves people. It is nice to know that something like that exists, regardless of any doctrine.

Who is your target audience and what is your message?

There is no privileged audience. Many of my works are intended for an uninformed collocutor, for a random viewer. I believe that art and artists have to address people’s habits and that is why I like the notion of a viewer returning home different than he or she was before. I like the idea of facing someone with a dilemma about the certainty of habits.

Is there an ideological vision? Can’t art be focused on a form, too?

Ideas definitely need a form; they need to be visible in order to travel. But I am not interested in pure form, form for the purpose of form. My work prefers action, even if includes other people.

Is art a political practice?

Everything that is done publicly is always political. Art cannot be just a viewpoint anymore. On the contrary, it has to take a position all the time, take responsibility.

Don’t you think there is too much rhetoric in such a statement?

No, because I am not interested in the clearly visible. I prefer oversights.

[○] After removing the first letter of the surname, Morbin becomes Orbin, which denotes a partially sighted person. The deformation of the artist’s name in the title of his performance, which is also used in the title of this interview, has an ironic connotation.