Giuseppe Gonella

Envolved

Milan (I), Galleria Giovanni Bonelli

September — October 2013

Painting for voyeurs

Daniele Capra

Paintings are fundamentally two-dimensional artworks, historically determined by the need to bring representations of reality on a surface. Of course, the last fifty years have brought us extreme examples that have taken artworks to conceptually defy the traditionally allocated space, such as the works of Alberto Burri or Lucio Fontana. As is universally recognized, it is a painting’s height and width that determine the space allotted to the visual content of the artwork: that is to say, the canvass is a finite, regular surface, and what is not included within it does not contribute to the making of the artwork.

The lenses of photographic devices can alter the visual angle, and thus the possibility of seeing with greater or lesser detail, but the visual angle of the human eye has its own inalterable characteristics. For this reason the dimension of an artwork establishes a (bi)univocal relationship with the viewer: beyond the subjective assessment on the content of an artwork and it aesthetic value, the dimensions of what we are seeing are relevant in terms of painting, since the relationship between our visual angle and the artwork cannot be modified.

Whilst an image – in terms of its status as a mental construct, or as an idea – does not necessarily require dimensions, the artwork must inevitably possess a physical dimension. This is because it is the result of a process whereby it is supposed to be observed by a person through their own eyes. This clearly affects one of its formal characteristics, that is, its composition: the logic governing the disposition of its different elements. Quite simply, some artworks are intended to be small, and others require a larger surface to interact with the viewer because they are intended to impress themselves upon a larger part of the retina. Height and width are also of fundamental importance, as they determine the visual strategy: with a vertical work we see the white space at the sides, while a horizontal one allows for margins above and below it. This formally inescapable modality is a static one: an artwork is determined from its very conception by the compositional choices of the artist, independently from its content and possible rethinking, since its surface is immutable and unique.

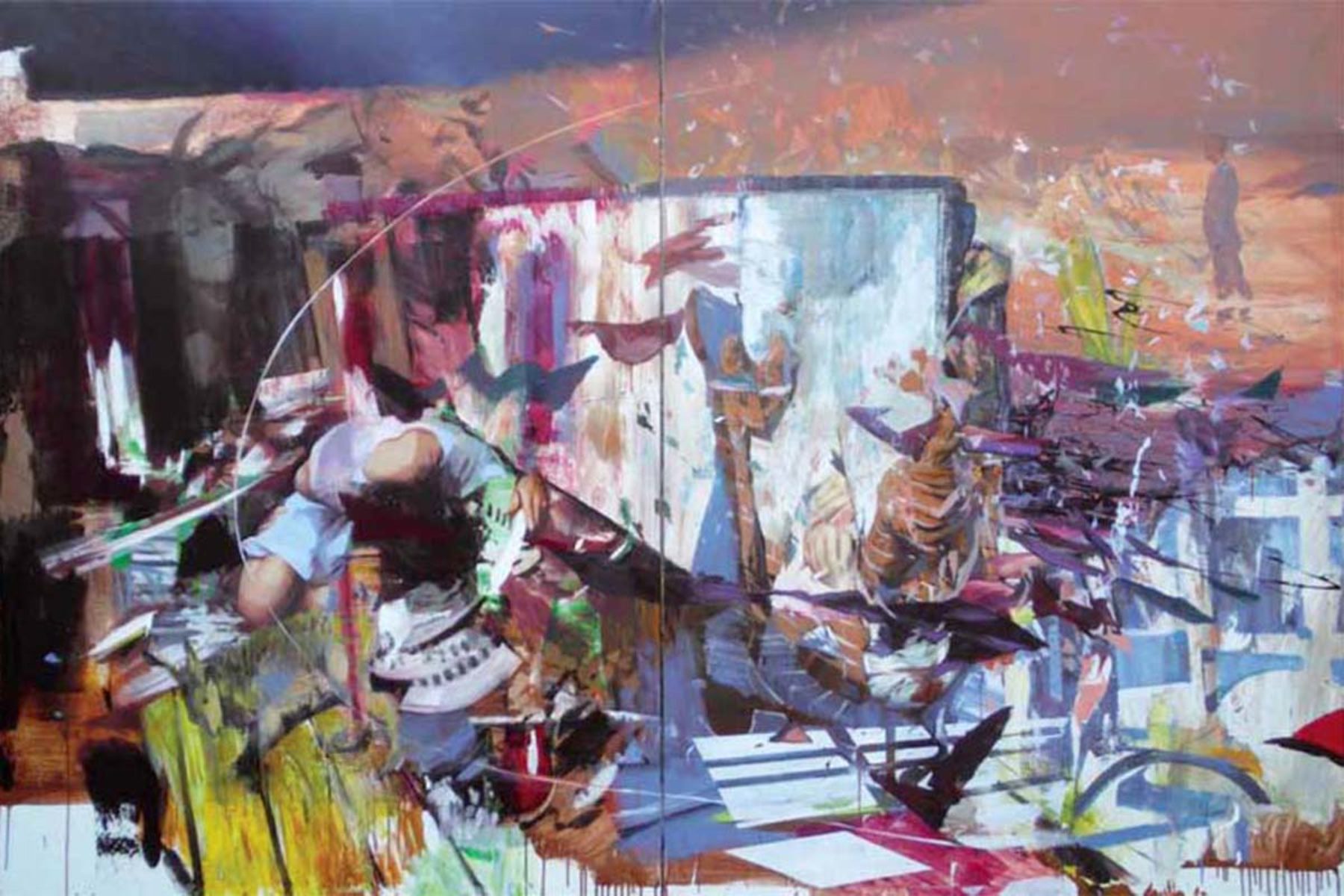

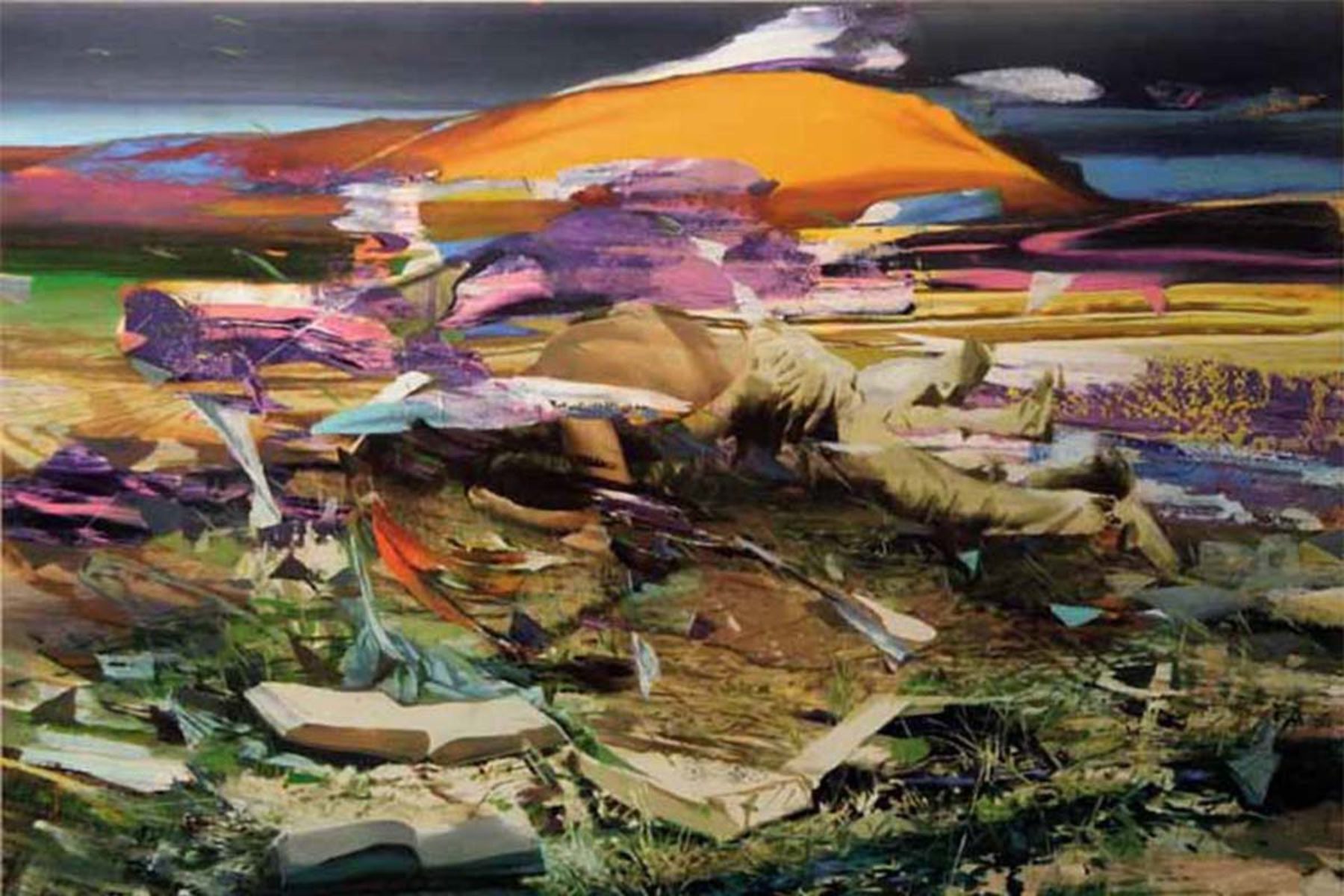

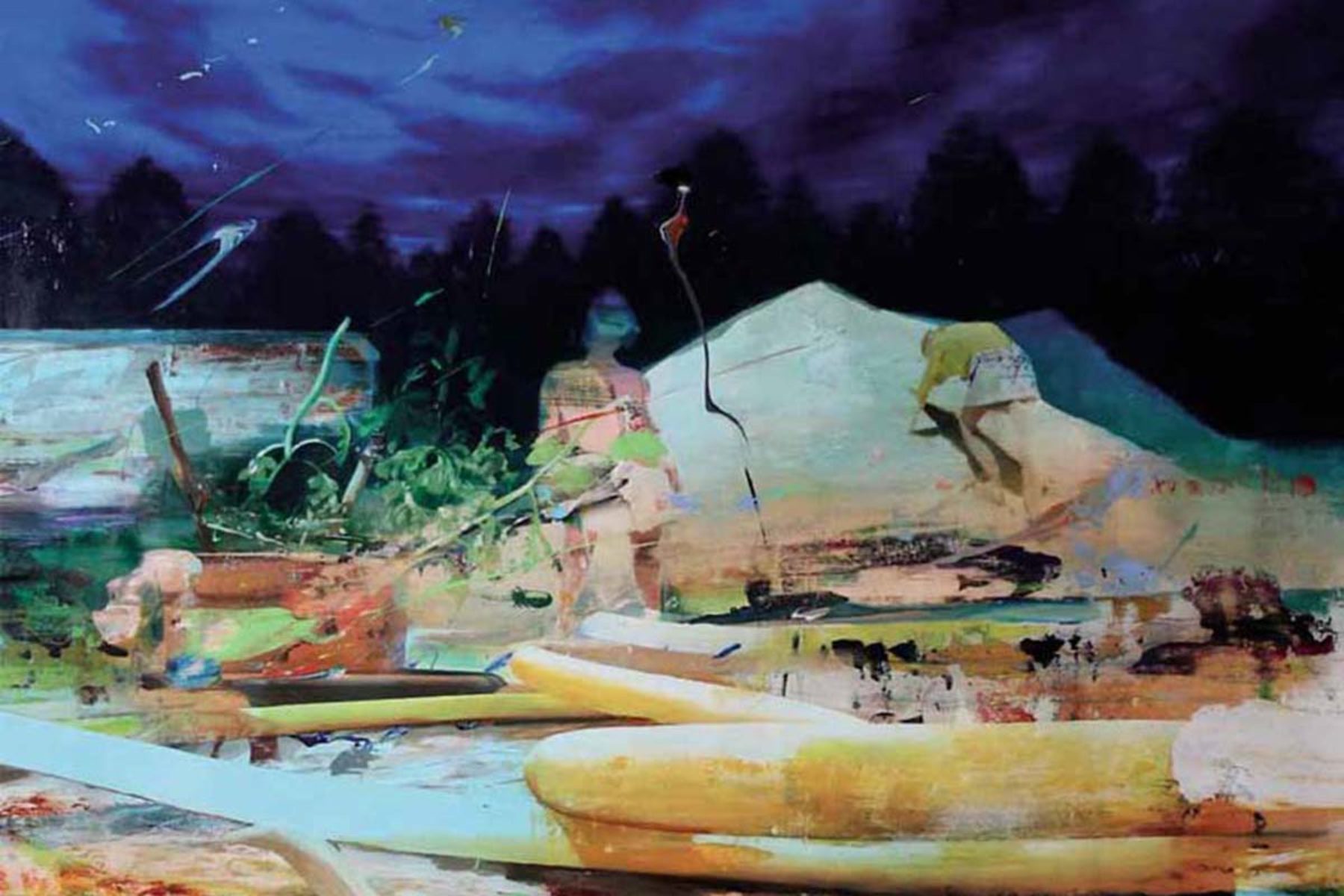

Giuseppe Gonella does not conform to such a process: he creates his works by painting on large rolls of canvass and then later cuts out the portions that constitute clusters of meaning thanks to their psychic energy, visual intensity and rhythm. The artist works by adding up and constituting compelling syntagms, to then start editing in a process which is similar to that of cinema editing, when different takes of a scene are put together.

Gonella thus applies to canvass the technique which is defined in the dictionary as “the technical operation of selecting and combining longer or shorter segments of developed film according to different criteria of selection and sequencing” (Pietro Montani describing «film editing» in the Encyclopaedia of Cinema published in 2004, by Istituto Treccani). It basically consists of creating a different sequence of the visual flow and rearranging the elements that have followed one another on the surface, in an additive form, so as to create a structure. Gonnella chooses the frame, that is the dimensions of the canvass and its orientation, thus determining its content and as a consequence the elements which are to be outside the picture, to be excluded. In this way the structure, made up of a cluster of both figurative and aniconic elements acquires the desired compositional thickness, as well as rhythm and, inevitably, meaning.

The artist’s approach is thus dynamic and non-academic, as it isn’t constructed in a linear, orderly manner, but rather through parataxis and accumulation. The smallest semantic units (a sign, a picture, an object) are juxtaposed with no pause between them, in an approach which uses aggregation and also has clear elements of chance. Its final cut, however, assures its formal cohesion, through a process of revision and rethinking. It is as if a piece of literature came from the sum of elements gathered by sampling from a dictionary. More than anything, it is as if the grammar that functionally supports each element of a sentence had been abolished and yet the sentences were perfectly understandable for the reader, who can only devote themselves to a careful work of scanning the artwork.

Gonella’s art is a pure form of painting, pouring out without design through the work carried out directly on the canvass. Nevermore so than here does the thought coincide with the execution and develop essentially in the course of the making, in the hours spent experimenting and working tentatively to then cut out and ponder on the aspects that don’t fit. The surface is covered by the continuous quivering of the elements that can be seen in realistic detail, in the primordial, gestural and dense brush stroke, in the aniconic plot. It is a whirlwind of details enveloping the viewer, further fuelled by the continuous agitation between figurative elements and aniconic parts. What emerges is a climactic executional vigour, and an imaginative tension which is at the same time erotic and a source of anxiety, for its thrilling magnetism, capable of making the viewer a voyeur unable to resist his own scopophilia. Pleased and aroused like one of the biblical old men watching and coveting Susan bathing.