Job moves

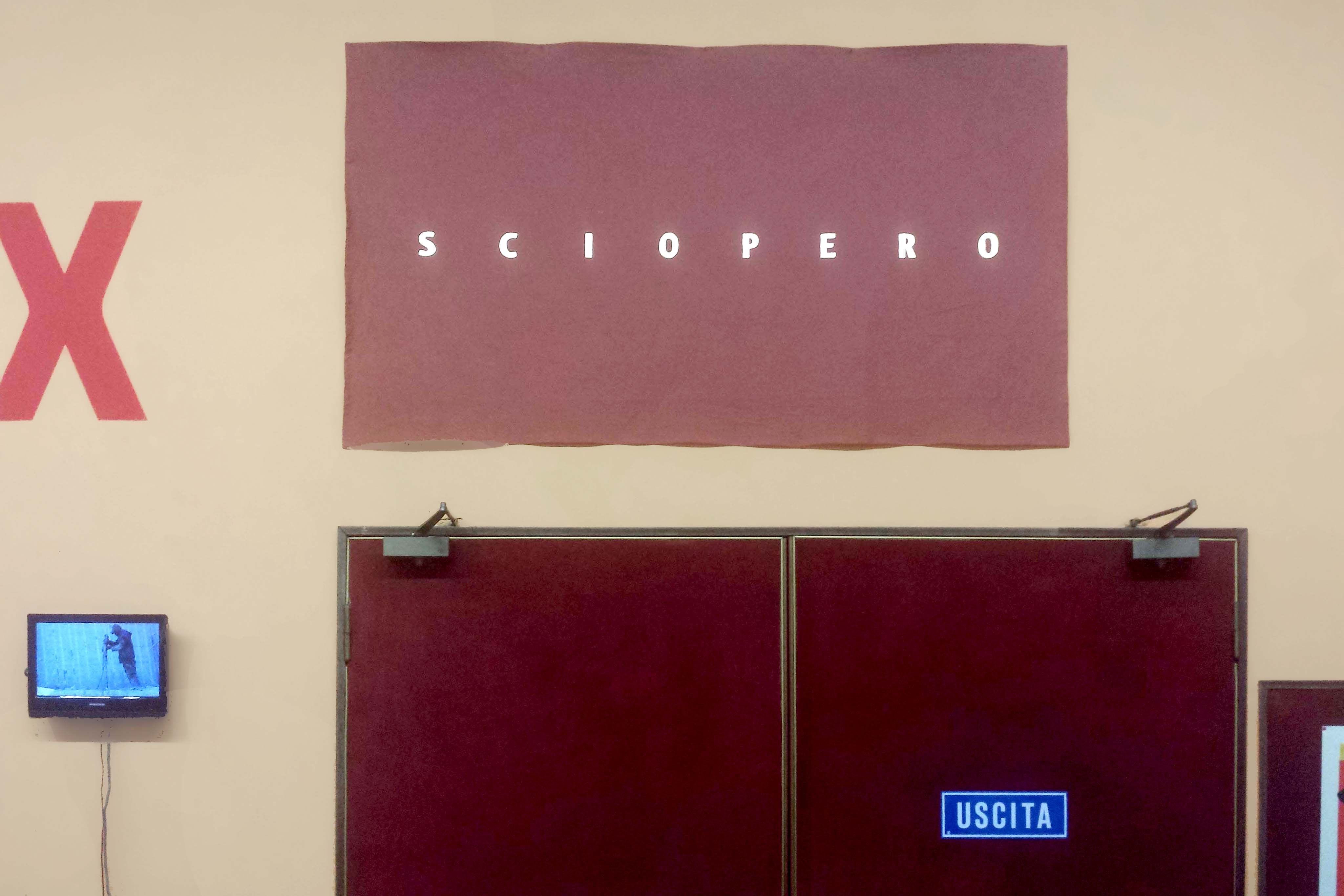

Padua (I), Cinema Rex

October 2016

Sorry for my outburst

Daniele Capra

Italy is a strange country. The often-quoted Article nr.1 of Italian Constitution says that our Republic is “founded on work”[1] where the word “work” is supposed to mean the industrious inclination of its citizens for creating, which is nothing else than the new version of the duty of growth expressed in the biblical order “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it”.[2] The idea of work, as intended by the constituent fathers, is the result of a compromise among Catholic, socialist and liberal politicians, and can be interpreted as Italian version of Max Weber’s Beruf, one of the essential elements of ethics that generated the modern capitalism,[3] or at least to it was one of the founding elements. The word Beruf is the expression and the form of a natural inclination in opposition to the otium, the contemplative life of antiquity.

Work is therefore negotium, the exercise of a right to have a job, but also a duty which is the starting-point of the social unity that founds the State – according to our constituents, and at the same time the fulfilment of people’s expressive potential. However, we rarely observe that work plays a similar role because it is more often considered a second-best, something useful to meet people’s economic needs. Otherwise the fact that everybody does its dream job seems to be, frankly, unachievable.

Whether we like it or not, work is a synonym for effort, a condition of captivity, sacrifice, commitment and not even respected as expected – in a country strange and ungrateful as Italy. For example, working in the cultural sector is not regarded as a real job: it’s a hobby. Creating artworks or writing about art is considered as a pastime suitable for bored rich people or incurable layabouts.

People who expect to be decently paid or generally respected believe in the impossible. Will Italy ever change? I doubt it. Working in the art field is not considered a professional matter. At least it can be considered as an independent activity that offers open-mindedness and freedom in terms of timing and methods. But, in spite of the usual complains of mine and my colleagues, I can assure that “It’s better than a serious job”.[4]

[1] The first article of the Italian Constitution, never changed since the foundation, says: “Italy is a Democratic Republic, founded on work. Sovereignty belongs to the people and is exercised by the people in the forms and within the limits of the Constitution”.

[2] See Holy Bible, Genesis, chapter 1:22 and 1:28.

[3] See M. Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

[4] I am misquoting Luigi Barzini’s famous joke about being a journalist: “Working as a journalist is hard, full of responsibilities that require long working hours even at the weekend or by night. But it’s better than a [serious] job!”.