Let’s Go Outside

Bianco-Valente, Shaun Gladwell, Alessandro Nassiri, Guido van der Werve, Devis Venturelli, Driant Zeneli

Milan (I), Superstudio Più

March 2010

TextWorks

The Brilliance of Wily E. Coyote

Daniele Capra

It doesn’t make much sense to ask if current art has certain and unequivocal answers for (post)modern man’s restlessness, given that the solutions to be found can only with difficulty be subjected to the test of verifiability with which science is obliged to confront itself (and as a result of which it can, at least in theory, distinguish what is true from what is false). And even more so because art shows itself to be a universe of ever increasing questions and lateral thinking; in other words, one that can hardly be measured against definite criteria because its enormous strength results from questioning the status quo, from the playful pleasures of manipulation and invention. As Lyotard has written, “In contemporary society and culture, […] the question of the legitimation of knowledge is formulated in different terms. The grand narrative has lost its credibility, regardless of what mode of unification it uses, regardless of whether it is a speculative narrative or a narrative of emancipation. The decline of narrative can be seen as an effect of the blossoming of techniques and technologies since the Second World War, […] or as an effect of the redeployment of advanced liberal capitalism”. [*] Art, instead, allows a recuperation of the narrative approach that Lyotard thinks has been discarded in favour of scientific efficiency and the development of the economic system, and it has put a spoke in his wheels.

Art, then, even though having an enormous capacity for the creation, appropriation, and elaboration of codes, still has as part of its nature a strong explosive component with regards the systems of thought that are available here at the start of the twenty-first century. This is a role which, in a certain sense, brings to mind Socrates and his position vis-à-vis the philosophical tradition that preceded him: simpler problems, a refusal of both rhetoric and the tradition of knowledge, and an approach that was not programmatic. In other words, an almost terrorist conceptual function, as was confirmed by the fact that it cost the philosopher his life. At the same time it is reasonable to expect that artists’ answers or proposed ways of escape are either on a reduced, even tiny, scale, and yet are unexpectedly interesting. But in this field the real value lies, not in the consistency of the solutions presented, in science itself, but rather in the creativity of the questions asked of the observer – of an aesthetic, political, and philosophical order.

It is fundamental that in the last twenty years of the twentieth century many of the macro-utopias that overpoweringly nourished the “brief century” (characterized by the entry of the masses into history, by rapid technological growth, and by various ideologies in the form of opposed -isms) slowly melted away. In other words, these all-devouring utopias – social, political and, at times, even aesthetic – did not take long to reveal all their heaviness and all their blunders, and they more or less rapidly collapsed under the weight of reality: the lightness that underpinned them, to paraphrase the famous novel by Milan Kundera, had become unbearable. In this situation of the end of history, so precociously analyzed by Francis Fukuyama at the beginning of the ‘nineties, the climate of temporal suspension had produced an ideological vacuum that had not been filled, with the effect of a continuous oscillation between a hardening and an extreme loosening of thought. In other words, the trend was that of polarization and the continual creation of small niches: this was demonstrated in the field of art by the pulverization of what, until thirty years earlier, had been movements, and by the fact that the resulting artistic practice became an individual activity.

After more than a decade trailing in the wake of this (individualistic) reaction, the last years of the past century witnessed, instead, the emergence of new ideas and new expectations that were overtly public or political, a result too of the new lymph injected by emergent countries: in fact, we often have the sensation that artists are rediscovering the social aspects of their work, as is shown by the great interest in the theme of cities and urban living, but also in the infiniteness of nature and the heroic aspects of living. Progressively, that is, after having long been smouldering under the ashes, thoughts about utopias are beginning to develop in art again, though not in an intimist manner and even less in an ideological one. These, in fact, are small utopias, without any presumption of explaining the world, but simply having the wish to offer or suggest visions and points of view that do not belong to us and that are, unexpectedly, something different: they are knots, discontinuities, virtuous accumulations that emerge after having sifted through a reality that no longer seems deeply satisfying. These are no longer simple evasions but genuine subversions that show us how an external view – beyond the curtain of normality and the humdrum – is both desirable and necessary. These are formidable, user-friendly Swiss knives for hacking through the hedge in order to see beyond it; they are Popeye’s spinach or the inspired and edgy inventions of Wile E. Coyote. And falling down into a canyon really will no longer be a problem.

Daniele Capra

It doesn’t make much sense to ask if current art has certain and unequivocal answers for (post)modern man’s restlessness, given that the solutions to be found can only with difficulty be subjected to the test of verifiability with which science is obliged to confront itself (and as a result of which it can, at least in theory, distinguish what is true from what is false). And even more so because art shows itself to be a universe of ever increasing questions and lateral thinking; in other words, one that can hardly be measured against definite criteria because its enormous strength results from questioning the status quo, from the playful pleasures of manipulation and invention. As Lyotard has written, “In contemporary society and culture, […] the question of the legitimation of knowledge is formulated in different terms. The grand narrative has lost its credibility, regardless of what mode of unification it uses, regardless of whether it is a speculative narrative or a narrative of emancipation. The decline of narrative can be seen as an effect of the blossoming of techniques and technologies since the Second World War, […] or as an effect of the redeployment of advanced liberal capitalism”. [*] Art, instead, allows a recuperation of the narrative approach that Lyotard thinks has been discarded in favour of scientific efficiency and the development of the economic system, and it has put a spoke in his wheels.

Art, then, even though having an enormous capacity for the creation, appropriation, and elaboration of codes, still has as part of its nature a strong explosive component with regards the systems of thought that are available here at the start of the twenty-first century. This is a role which, in a certain sense, brings to mind Socrates and his position vis-à-vis the philosophical tradition that preceded him: simpler problems, a refusal of both rhetoric and the tradition of knowledge, and an approach that was not programmatic. In other words, an almost terrorist conceptual function, as was confirmed by the fact that it cost the philosopher his life. At the same time it is reasonable to expect that artists’ answers or proposed ways of escape are either on a reduced, even tiny, scale, and yet are unexpectedly interesting. But in this field the real value lies, not in the consistency of the solutions presented, in science itself, but rather in the creativity of the questions asked of the observer – of an aesthetic, political, and philosophical order.

It is fundamental that in the last twenty years of the twentieth century many of the macro-utopias that overpoweringly nourished the “brief century” (characterized by the entry of the masses into history, by rapid technological growth, and by various ideologies in the form of opposed -isms) slowly melted away. In other words, these all-devouring utopias – social, political and, at times, even aesthetic – did not take long to reveal all their heaviness and all their blunders, and they more or less rapidly collapsed under the weight of reality: the lightness that underpinned them, to paraphrase the famous novel by Milan Kundera, had become unbearable. In this situation of the end of history, so precociously analyzed by Francis Fukuyama at the beginning of the ‘nineties, the climate of temporal suspension had produced an ideological vacuum that had not been filled, with the effect of a continuous oscillation between a hardening and an extreme loosening of thought. In other words, the trend was that of polarization and the continual creation of small niches: this was demonstrated in the field of art by the pulverization of what, until thirty years earlier, had been movements, and by the fact that the resulting artistic practice became an individual activity.

After more than a decade trailing in the wake of this (individualistic) reaction, the last years of the past century witnessed, instead, the emergence of new ideas and new expectations that were overtly public or political, a result too of the new lymph injected by emergent countries: in fact, we often have the sensation that artists are rediscovering the social aspects of their work, as is shown by the great interest in the theme of cities and urban living, but also in the infiniteness of nature and the heroic aspects of living. Progressively, that is, after having long been smouldering under the ashes, thoughts about utopias are beginning to develop in art again, though not in an intimist manner and even less in an ideological one. These, in fact, are small utopias, without any presumption of explaining the world, but simply having the wish to offer or suggest visions and points of view that do not belong to us and that are, unexpectedly, something different: they are knots, discontinuities, virtuous accumulations that emerge after having sifted through a reality that no longer seems deeply satisfying. These are no longer simple evasions but genuine subversions that show us how an external view – beyond the curtain of normality and the humdrum – is both desirable and necessary. These are formidable, user-friendly Swiss knives for hacking through the hedge in order to see beyond it; they are Popeye’s spinach or the inspired and edgy inventions of Wile E. Coyote. And falling down into a canyon really will no longer be a problem.

[*] J.F. Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, University of Minnesota Press, 1984, pp. 37-38.

The works

Daniele Capra

Bianco-Valente

Entità risonante, 2009, video, 3’35’’, courtesy the artists

We usually write down whatever we want to record, in order to hold on to it, and preserve it. From a shopping list to an essay on ancient history, we entrust to writing any concept we wish to last for longer than a few moments. Even music – which is born, lives, and dies only and always in an instant – needs to be physically deposited on a support that can contain its traces and symbols.

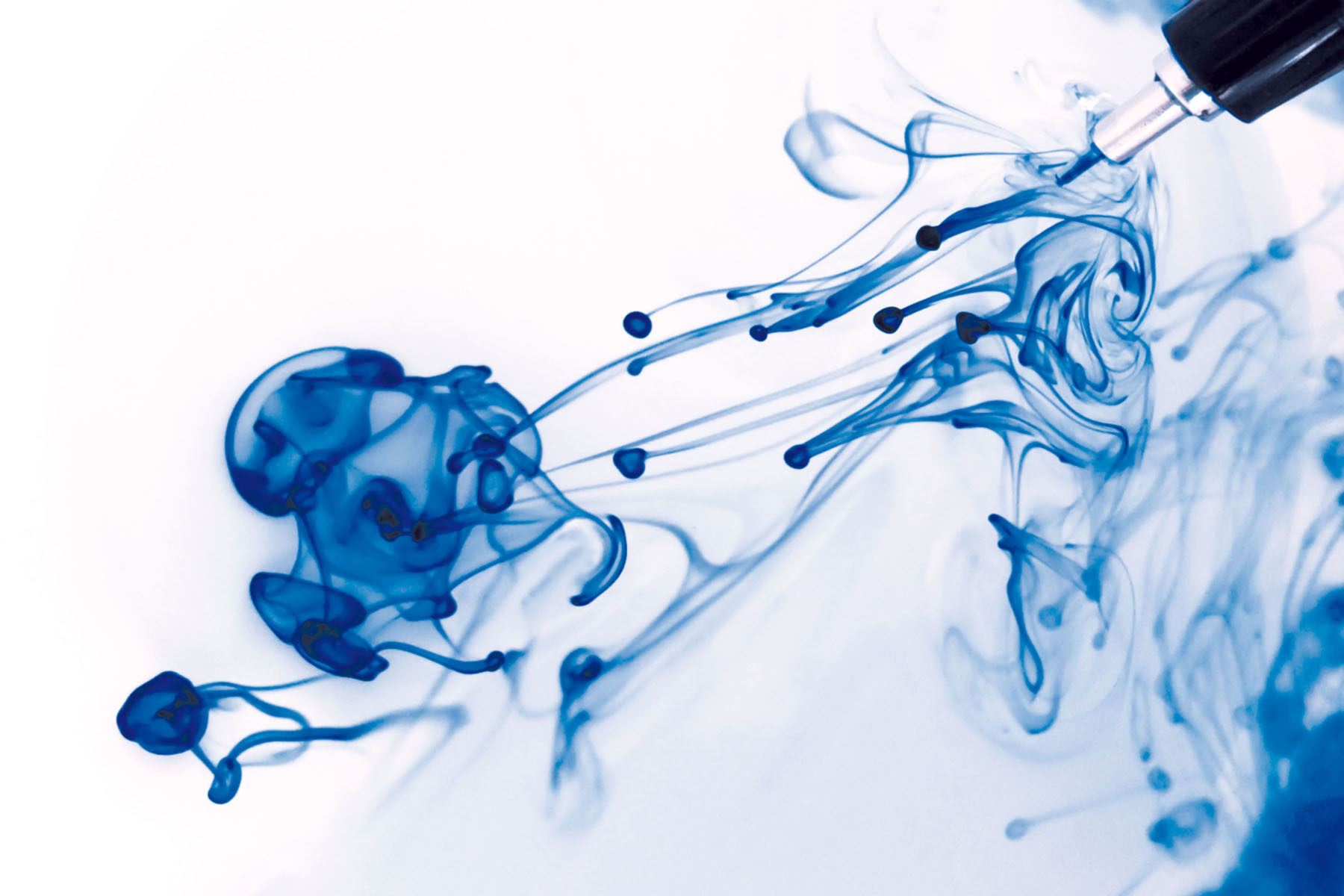

In Entità risonante the words are written, instead of in water, with a pen. And for a moment the liquid seems able to contain the form and meaning. Then, slowly, the vibration within the liquid spreads the marks which become dancing stains of blue ink, just as the viewer inevitable expects. Scripta manent? Perhaps we have trusted in this Latin proverb for too long.

Shaun Gladwell

In a Station of the Metro, 2006, 2 channels video, 10’35’’, courtesy Studio La Città, Verona

A busy subway station, an unexpected contest in the middle of the crowd by some young break-dancing enthusiasts. A contest in any city whatever in any continent whatever. Then, suddenly, “the apparition of these faces in the crowd”, as the first verse of Ezra Pound’s distich (In a Station of the Metro) says and which inspired this work.

And, like a haiku, two horizontally-placed videos harmonize and contrast in a hypnotic rhythm. A continual questioning and answering, like one of Bach’s two-part fugues in which the elements interact and chase after each other at a certain distance: similar but without necessarily being the same. And in movement and development they find a subtle and disturbing balance that glues the eye to vision.

Alessandro Nassiri

Once Elephants used to fly, 2008, 3’, courtesy the artists

Perhaps they are nothing more than watery vapour, but clouds can be anything: they are the projections of our imagination which allow us to discover in their form whatever our thoughts suggest. To imagine animals, battles, supermen is a game that we play as children and which we then no longer want to continue, either from laziness or because we no longer wish to lift up our head.

What the artist tries to do in his wanderings around Istanbul, on a motorbike and with a camera in his hand, is an impossible challenge: to film a cloud shaped like an elephant. He does so without worrying about the city, the traffic, or the roofs of the buildings. A utopia that is almost within his grasp, one to be chased among the fragments of blue before the wind of the Bosphorus finally scatters it in the sky.

Guido van der Werve

Nummer acht. Everything is going to be alright, 2007, 16 mm to HD video, 10’10’’, courtesy the artist, Marc Foxx, Los Angeles, Juliette Jongma, Amsterdam, Monitor, Rome

In the white snow a man walks over the ice: ineffably calm, uncaring of what happens behind him. He is tiny and defenceless in the face of the enormous icebreaker which follows him at a short distance, as swollen and fat as Moby Dick. The man is a romantic hero from a painting by Caspar Friedrich: he measures himself against nature in search of the absolute, the sublime.

His is an act of defiance in the face of an extreme and hostile place, of immanent danger. An unbearable tension transforms every one of his steps into magic: he constantly seems to bypass the abyss, careless of his thorny path, of his fate. We will never know what might actually happen but we would like to have the courage that he so strongly demonstrates.

Devis Venturelli

Continuum, 2008, video, 6’, courtesy De Faveri Arte, Feltre

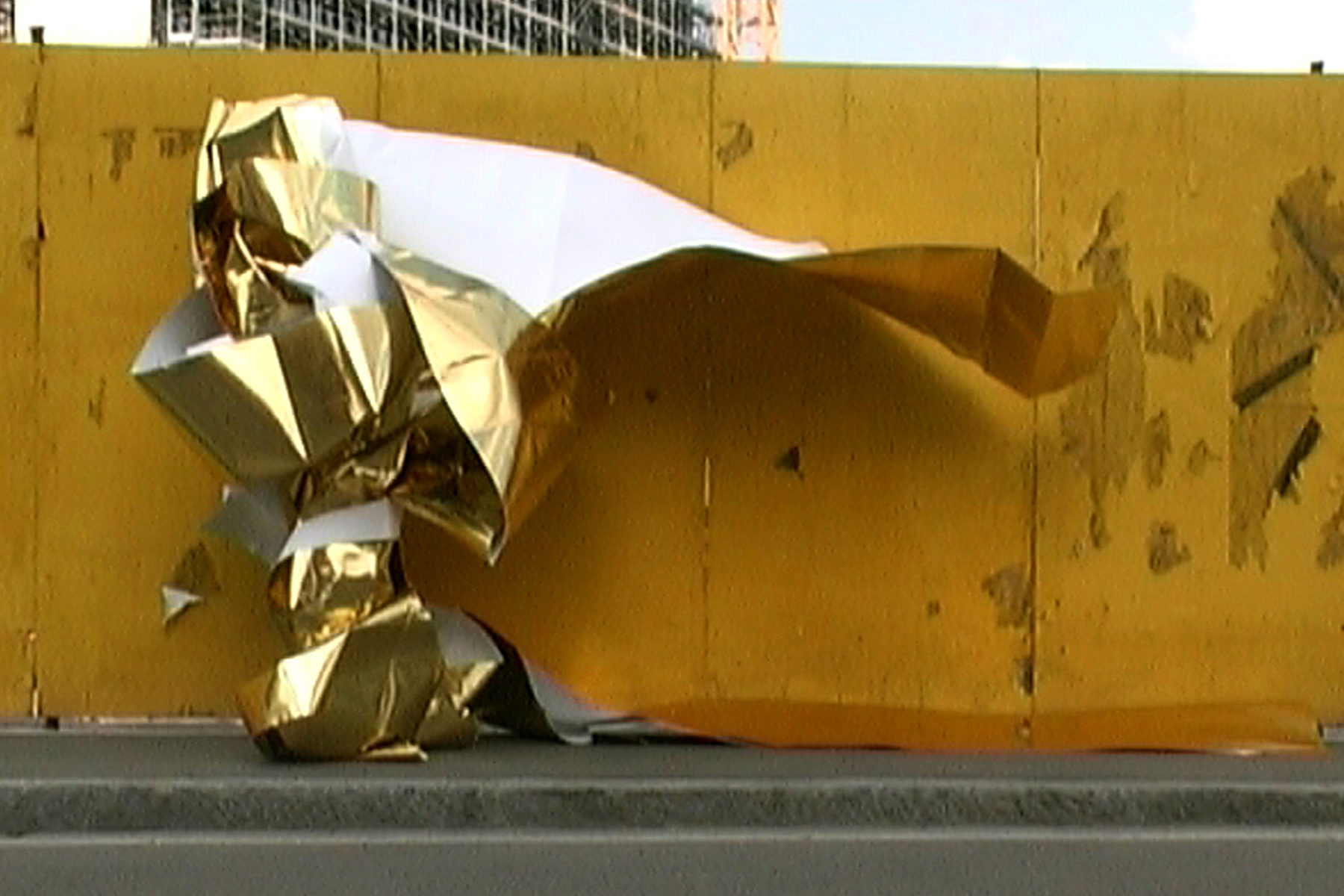

In Continuum, Devis Venturelli races around the neighbourhood of a city still under construction. The urban context is hardly sketched in but we can intuit the forms of the buildings – wrapped in scaffolding and surrounded by cranes – that lie behind the enclosing walls and which are to be the city of the future. On the asphalt, instead, are all the traces of a building site with its barriers, plastic trellises, and sand.

In fact the artist chooses to run with a shiny gold-coloured ribbon that escapes from all about him and which at times makes him seem to have the sculptural shapes of Boccioni’s Forne uniche della continuità nello spazio. But this is not only a question of acrobatics or a breathless race. Venturelli, in fact, seems a creature that can arouse amazement, or that might be a zoomorphic being stepping out of a fanciful and post-modern bestiary. Uninterruptedly.

Driant Zeneli

The Dream of Icarus was to make a Cloud, 2009, 4’05’, courtesy the artist

Flying has always been one of the activities that has most enthralled mankind from the beginning of civilization. Icarus was forced to collide against his own ambitions and inadequacy. Zeneli, instead, has decided on something closer at hand, something which, in a certain sense, is more fragile and anti-heroic: to create a cloud. A simple, and ephemeral gesture that does not seem to produce anything of value.

Having been carried by a professional athlete, the artist in fact undertook a paragliding journey during which he trailed white powder that condensed in the air to form clouds. A lot of effort in order to produce a highly rapid and not very noticeable action. Clouds, in fact, last just a few seconds and then disappear in the winds among the mountains. There is nothing else to do than be led by the hand and feel the breeze.

Daniele Capra

Bianco-Valente

Entità risonante, 2009, video, 3’35’’, courtesy the artists

We usually write down whatever we want to record, in order to hold on to it, and preserve it. From a shopping list to an essay on ancient history, we entrust to writing any concept we wish to last for longer than a few moments. Even music – which is born, lives, and dies only and always in an instant – needs to be physically deposited on a support that can contain its traces and symbols.

In Entità risonante the words are written, instead of in water, with a pen. And for a moment the liquid seems able to contain the form and meaning. Then, slowly, the vibration within the liquid spreads the marks which become dancing stains of blue ink, just as the viewer inevitable expects. Scripta manent? Perhaps we have trusted in this Latin proverb for too long.

Shaun Gladwell

In a Station of the Metro, 2006, 2 channels video, 10’35’’, courtesy Studio La Città, Verona

A busy subway station, an unexpected contest in the middle of the crowd by some young break-dancing enthusiasts. A contest in any city whatever in any continent whatever. Then, suddenly, “the apparition of these faces in the crowd”, as the first verse of Ezra Pound’s distich (In a Station of the Metro) says and which inspired this work.

And, like a haiku, two horizontally-placed videos harmonize and contrast in a hypnotic rhythm. A continual questioning and answering, like one of Bach’s two-part fugues in which the elements interact and chase after each other at a certain distance: similar but without necessarily being the same. And in movement and development they find a subtle and disturbing balance that glues the eye to vision.

Alessandro Nassiri

Once Elephants used to fly, 2008, 3’, courtesy the artists

Perhaps they are nothing more than watery vapour, but clouds can be anything: they are the projections of our imagination which allow us to discover in their form whatever our thoughts suggest. To imagine animals, battles, supermen is a game that we play as children and which we then no longer want to continue, either from laziness or because we no longer wish to lift up our head.

What the artist tries to do in his wanderings around Istanbul, on a motorbike and with a camera in his hand, is an impossible challenge: to film a cloud shaped like an elephant. He does so without worrying about the city, the traffic, or the roofs of the buildings. A utopia that is almost within his grasp, one to be chased among the fragments of blue before the wind of the Bosphorus finally scatters it in the sky.

Guido van der Werve

Nummer acht. Everything is going to be alright, 2007, 16 mm to HD video, 10’10’’, courtesy the artist, Marc Foxx, Los Angeles, Juliette Jongma, Amsterdam, Monitor, Rome

In the white snow a man walks over the ice: ineffably calm, uncaring of what happens behind him. He is tiny and defenceless in the face of the enormous icebreaker which follows him at a short distance, as swollen and fat as Moby Dick. The man is a romantic hero from a painting by Caspar Friedrich: he measures himself against nature in search of the absolute, the sublime.

His is an act of defiance in the face of an extreme and hostile place, of immanent danger. An unbearable tension transforms every one of his steps into magic: he constantly seems to bypass the abyss, careless of his thorny path, of his fate. We will never know what might actually happen but we would like to have the courage that he so strongly demonstrates.

Devis Venturelli

Continuum, 2008, video, 6’, courtesy De Faveri Arte, Feltre

In Continuum, Devis Venturelli races around the neighbourhood of a city still under construction. The urban context is hardly sketched in but we can intuit the forms of the buildings – wrapped in scaffolding and surrounded by cranes – that lie behind the enclosing walls and which are to be the city of the future. On the asphalt, instead, are all the traces of a building site with its barriers, plastic trellises, and sand.

In fact the artist chooses to run with a shiny gold-coloured ribbon that escapes from all about him and which at times makes him seem to have the sculptural shapes of Boccioni’s Forne uniche della continuità nello spazio. But this is not only a question of acrobatics or a breathless race. Venturelli, in fact, seems a creature that can arouse amazement, or that might be a zoomorphic being stepping out of a fanciful and post-modern bestiary. Uninterruptedly.

Driant Zeneli

The Dream of Icarus was to make a Cloud, 2009, 4’05’, courtesy the artist

Flying has always been one of the activities that has most enthralled mankind from the beginning of civilization. Icarus was forced to collide against his own ambitions and inadequacy. Zeneli, instead, has decided on something closer at hand, something which, in a certain sense, is more fragile and anti-heroic: to create a cloud. A simple, and ephemeral gesture that does not seem to produce anything of value.

Having been carried by a professional athlete, the artist in fact undertook a paragliding journey during which he trailed white powder that condensed in the air to form clouds. A lot of effort in order to produce a highly rapid and not very noticeable action. Clouds, in fact, last just a few seconds and then disappear in the winds among the mountains. There is nothing else to do than be led by the hand and feel the breeze.