Linda Carrara

Il pretesto di Lotto

Trento (I), Galleria Boccanera

October ― November 2016

Reality, suspended angels and metamorphosis

Daniele Capra

Linda Carrara’s work arises from a reflection on the conceptual and mimetic dynamics of painting, and questions its representative intentions. It focuses on a free practice based on the creation of new worlds and new realities that produce entirely new visual relationships. In particular, the subject and the compositional structure, which are central elements in figurative practice, are just a pretext in the artist’s work, an opportunity to create an imaginative and suspended reality which leads the viewer elsewhere.

In general, differently to what we might generally think, the practice of figuration is not aimed at reality in itself. Its purpose is neither to copy reality (an aspect that Plato found deplorable), nor to represent it (as in Baudrillards’ famous simulacra). Indeed, this practice works around reality and changes it. In other words, it proposes a new and different reality, an incandescent material that can be understood only by those who have the sensitivity and the skills to interpret its linguistic codes. This situation is the result of two modern trends. The first one is the artist’s awareness of their own role, a situation which has gradually developed from the fifteenth century onwards. Thanks to this perception, artists have become aware of the importance of their own art and of their own intellectual work. They are finally free from being solely a vehicle for the content of their work, humble servants to the needs of their customers. The second aspect is a conceptual and anti-realist rift, in opposition to the idea of mimesis, which was seen with some artists from the late sixteenth century. These were the Mannerists, and they continued the strong anti-naturalist tendency that was the first to overcome, in linguistic terms, the limit which, until then, had only been considered as an oddity. We might consider that the twentieth-century avant-gardes, with their indirect way of relating to reality, have carried forward this approach, whether they are aware of it or not.

Linda Carrara’s artwork is a tributary of this river. Her painting is not like the work of a meticulous scribe’s, compelled to write down what he hears among all the background noise, nor is it the effect of a maverick hero’s forceful opposition to the stream of reality. Rather it is the consequence of a completely new, deeper drive that causes a deviation. In her work, painting is no longer either the child or the heir of reality: quite the opposite, it is a new character which increases all possible realities thanks to its own existence.

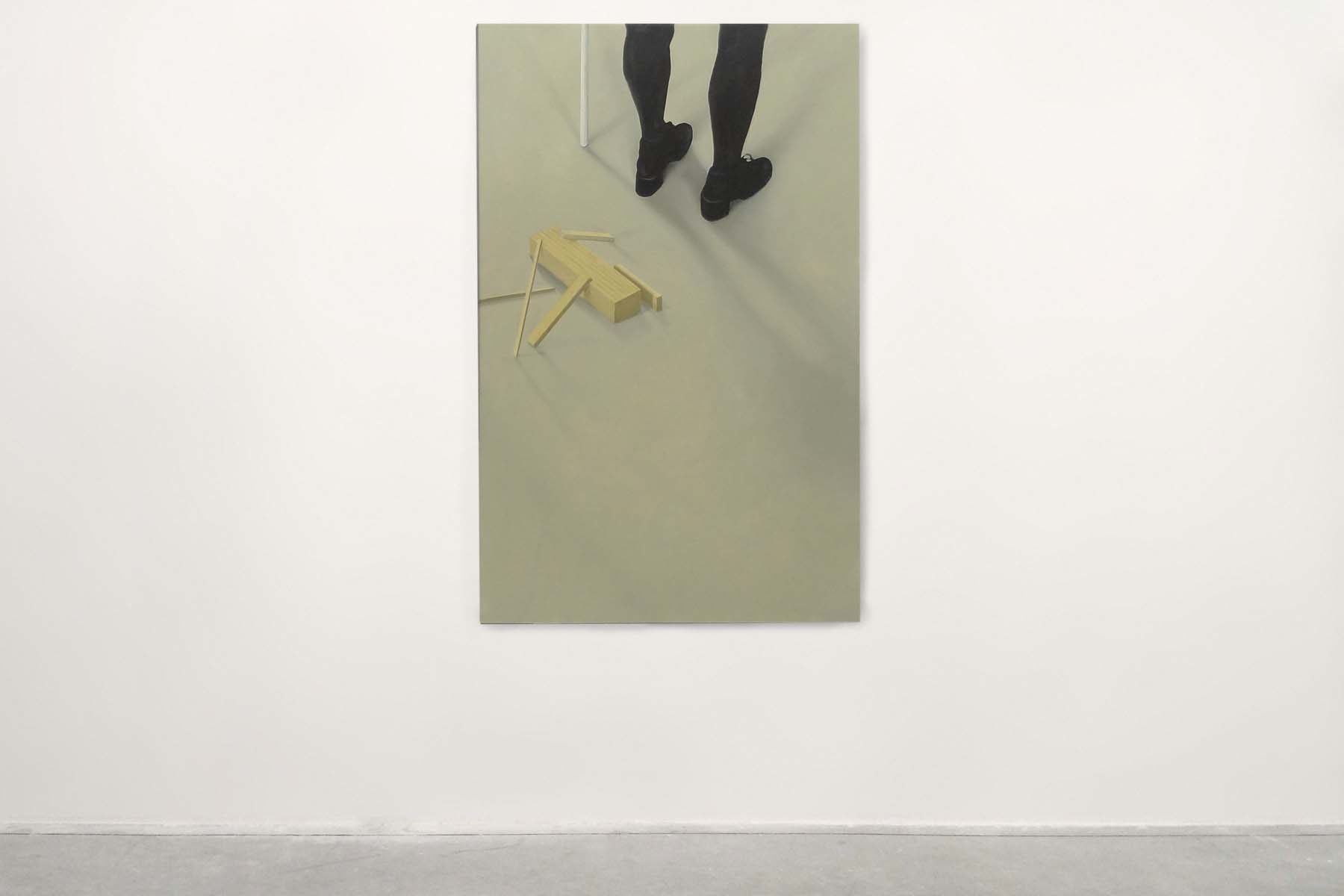

The objects displayed on the surface of her works are merely an excuse to challenge the cognitive value attributed to reality. In Linda Carrara’s research, painting itself is the hidden subject of her work, since it is the medium that evokes unconventional features of reality. In this way, her pictures are characterised by a free and precarious syntax, filled with silent poetic bewilderment and genuine contradictions of perspective. Pieces of wood, marble surfaces, sticks and small objects all serve to confirm the fact that they are not themselves, exactly as the writing states under Magritte’s famous pipe.

The artist’s work questions and embarrasses the viewer, encouraging them to talk about or speak of something else, without the need to be consistent with the topic or the nature of the context. In other words, Carrara’s artworks function as surreal and process-based devices which lead to a visual and thematic divergence. The title of the exhibition itself, Il pretesto di Lotto (The pretext of Lotto), is proof of this attitude. Indeed, her works led to wide-ranging discussions about many questions of art history which were relevant to the painting of Lorenzo Lotto. For example, there was a discussion about the natural/anti-natural sense of flight, as seen in the Trinity at the Bernareggi Museum, where Christ flies through the air illuminated from behind. Or about the Jesi Annunciation, where the Archangel is depicted suspended before he touches the ground. Or, again, about the Martinengo Altarpiece, where the angels hold the Madonna’s crown in their hands. I’ll not go into what led to this bewildering intellectual pleasure, but, even without discussing Carrara’s research (and over cookies and several coffees) to talk about something else was the best way to talk, intensely, about the deepest reasons for her artistic practice. A practice that ultimately encompasses suspension, change of direction, transformation and metamorphosis.