Linda Carrara

La fatigue de ne pas finir

Brussels (B), Musumeci Contemporary

November 2017 ― January 2018

La fatigue de ne pas finir

Daniele Capra

Linda Carrara’s artistic practice is characterized by a painting whose figurative elements are the starting point of an inquiry into reality and its modes of representation. Her research is imbued with a deep experimental tension, evident both through the work’s subject and in terms of language. More to the point, Carrara’s painting is the fruit of an expressive choice aiming at unveiling the content of the intimate interstices of things. Ontological by nature, her analysis expresses a strong lyrical component, although less visible in the heroic digging of the matter than in the questioning of the observer. In fact, the work – fully completed in artistic terms – lays unaccomplished as to its interpretation, and asks for an effort at understanding and renegotiating with its subject.

What is shown here is a process painting, made of material gestures and technique, while the subject is often no more than a pretext, if not just an excuse, hiding an inquiry into the meta-pictorial and metaphysics. Carrara does not show the visible, the mere film surrounding the objects’ and the world’s surface; she alludes to that thick and profound substratum within which the Being endlessly sinks. Thus, the almost total disappearing of the subject becomes a tool for freeing painting of its representative functions in favour of an artistic practice rooted into the definition of flux and the control of randomness. In this perspective, the fatigue de ne pas finir a work tells how her thought and the relentless revision/rereading of reality push the artist toward the difficulty of finding the final, fixed, form, the one that cannot be bettered or modified. Ne pas finir springs out of the willingness of abstaining from the gesture which could definitively shut/seal the microcosm of acts generating the work.

As the artist said during one of our talks, the fatigue of not terminating a work “is what survives the natural selection, the laziness, careful analysis”, the outcome’s expectation. It’s an effort arising out of the attempt at preserving the thousands chances, the thousands possible facets, still inherent in the artwork. What is at stake here is the search for a poetic revelation, one which avoid to transmit to the observer a content held by the image’s form.

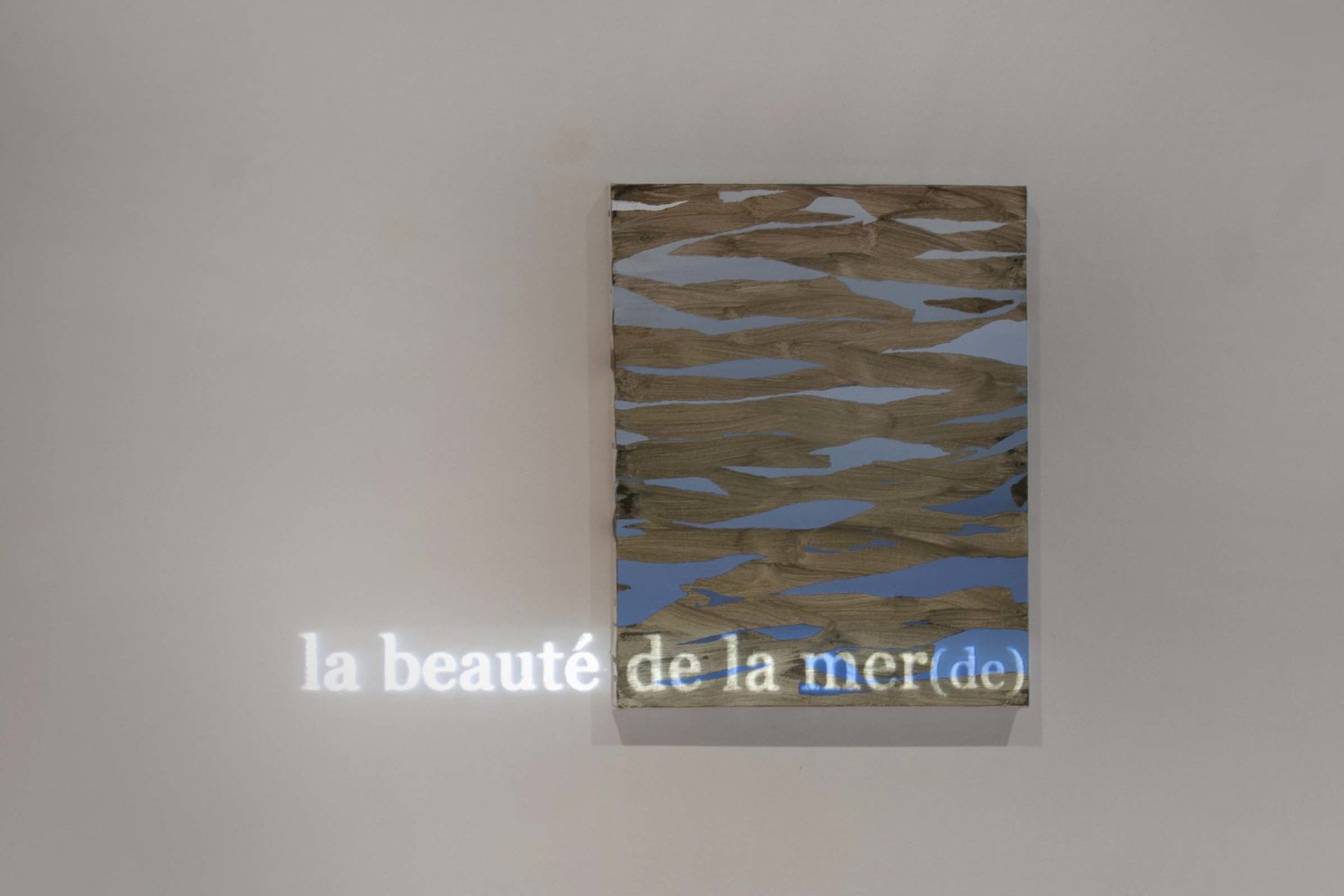

The Brussels open studio follows a stay in Kronstadt (Saint Petersburg), during which the artist studied water and the floating objects – leaves, wood pieces, rubbish, and even human belongings – that seas, rivers, or channels, bring about. Once back in the Belgian capital, she started an in-depth exploration of the city channels, ending up with the choice as pictorial subject of the very same water surface, and the endlessly changing materials going along. By no means, though, this makes room for the exactitude inherent to the concept of representation, as what is aimed at is rather showing the outcome of a manual work by which the artist stresses the multiform sides of the likelihood linking the random act of painting with reality.

The large works on paper placed on the walls reproduce the suggestions of the fluid element in a realistic and likely way, according to the Quadraturismo conceptual modes of the mid-XVI century, which aimed at visually bringing within a given space the perspectives and pieces of the outside, or the most far away, world. Such an artifice places simultaneously the observer in two spatial contexts, allowing him to live where he really is while receiving some visual information either from elsewhere, or from the fictional world devised by the artist. In this fashion, Carrara transfers to the vertical dimension the water fluxes that are normally flowing horizontally, thus denying the basic assumptions of the quadratura, i.e., the research and the construction of a perspective able to trespass the bi-dimensionality imposed by the supporting surfaces. As a matter of fact, the artist sticks to the walls the bi-dimensional flowing of watercourses, showing real size details of their surfaces and using aerial views, which are by themselves substantially flat, almost a map of the fluid element. By a fully unconventional choice, the two (and two only) dimensions of the subject are thus brought back to the two dimensions of representation.

But the real Carrara’s goal is to concoct a perfect stratagem for puzzling the observer by an ideological reversal of works which, though seeming at first sight mere trompe-l’oeil, have little or nothing in common with whatever pleasant, sought for, subject, in keeping with the tastes of those who like decorating walls with moving, edifying, or plainly beautiful, images. Indeed, these pieces show many layers of powder, filth, pollution, natural and even human remains: shortly, all what we don’t like to see, or are used to remove automatically and unconsciously. Contrariwise, Carrara’s suggestive stratification of visual elements emphasizes what is lying at the subject’s periphery, on the torn border of the figuration and the aniconic. Unrecognizable, trivial, suspended forms, allying melancholy and dazzling seduction.