Luciana Tămaș

Ninnananna

Trieste Contemporanea, Trieste (I)

December 2022 ― February 2023

Potential weapons and impertinent questions

Daniele Capra

1.

In the process of growth, play enables children to emotionally explore conflict while simultaneously learning to recognise and channel their physical, psychological, and verbal aggression. Games such as simulated fights, warfare, and the use of both realistic and imaginary weapons allow children to delve into uncharted realms of their emotions, expressing their actions symbolically. Gregory Bateson notes: “In ordinary parlance, ‘play’ is not the name of an act or action; it is the name of aframe for action.”[1] In this context, “play could only occur if the participant organisms were capable of some degree of meta-communication, i.e., of exchanging signals which would carry the message ‘this is play’.”[2]

2.

Indeed, the game serves as a self-cognitive means of experiencing feelings, emotions, and uncertainties before they manifest in life, with all their disruptive complexities. The implicit meta-communicative assumption, on the other hand, acts as a guarantor by creating a context that isolates the moment of play, keeping it somewhat detached from reality. Hence, the game can be perceived as a fictional state, a sort of mise-en-scène with internal rules established through explicit agreement among the involved parties. However, there is no audience or representation other than those participating in it; the agents themselves are the sole recipients of the action, which must be interpreted differently from ordinary customs.

3.

It is reasonable to consider that the play framework elucidated by Bateson is equally applicable to contemporary works of art, which, by their very nature, transcend the norms and purposes to which other human creations or artifacts are bound. Objects typically serve diverse needs over time, functioning as tools, instruments, and items for practical, ritualistic, decorative, communicative, recreational, and symbolic purposes (even though, in the last fifty years, objects have frequently proliferated uncontrollably due to consumerism [3]). . A lot of object-based works, serving as both physical objects and artworks, are distinguished by their programmatically different purpose: the interrogative function. They are designed to pose one or more questions concerning the physical, temporal, or anthropological context in which they are placed, and to observers who encounter them. In this scenario, the interpretive framework of art allows us to view the works through different lenses compared to everyday phenomena, often intentionally embodying an ambiguity where various interpretative registers overlap.

4.

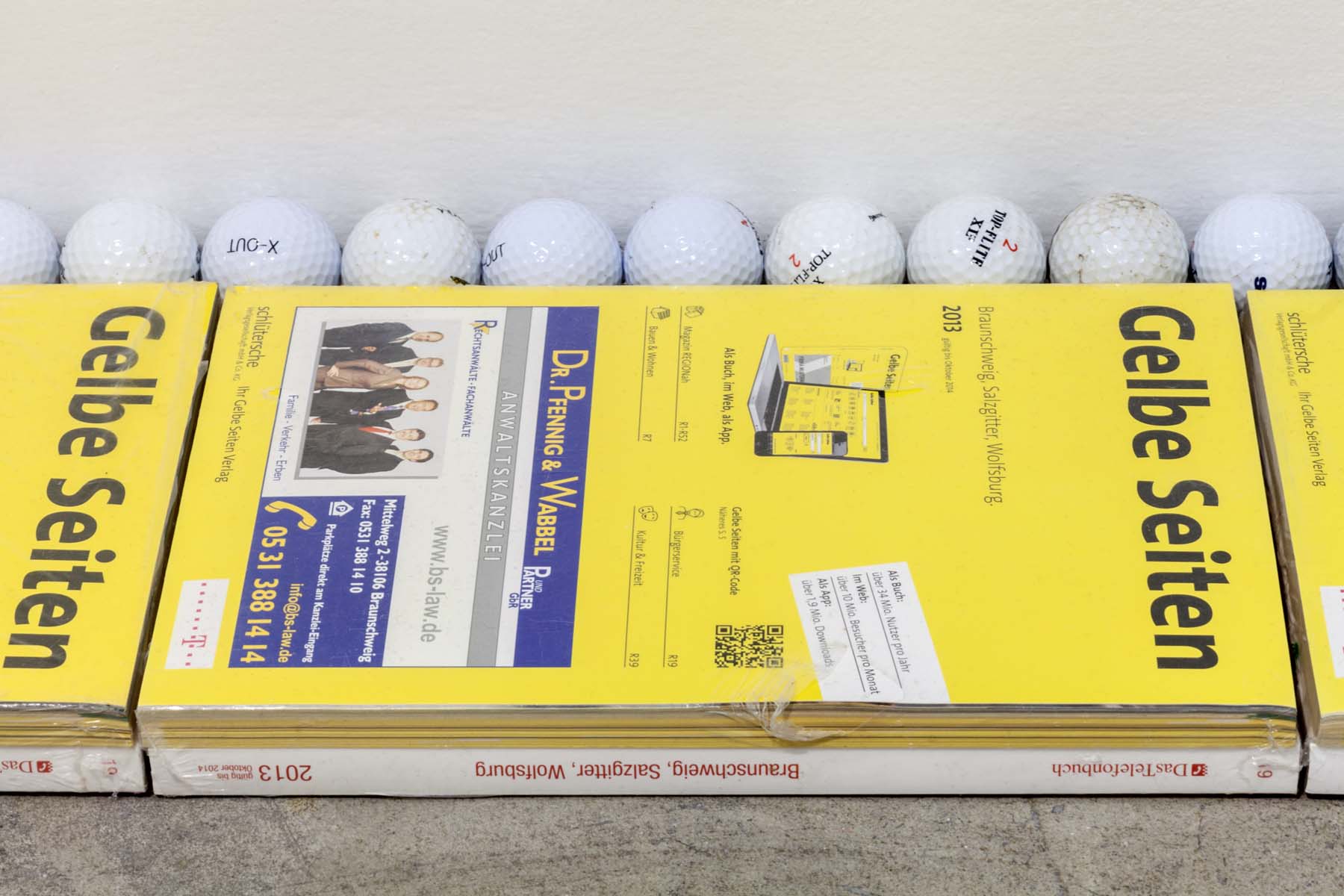

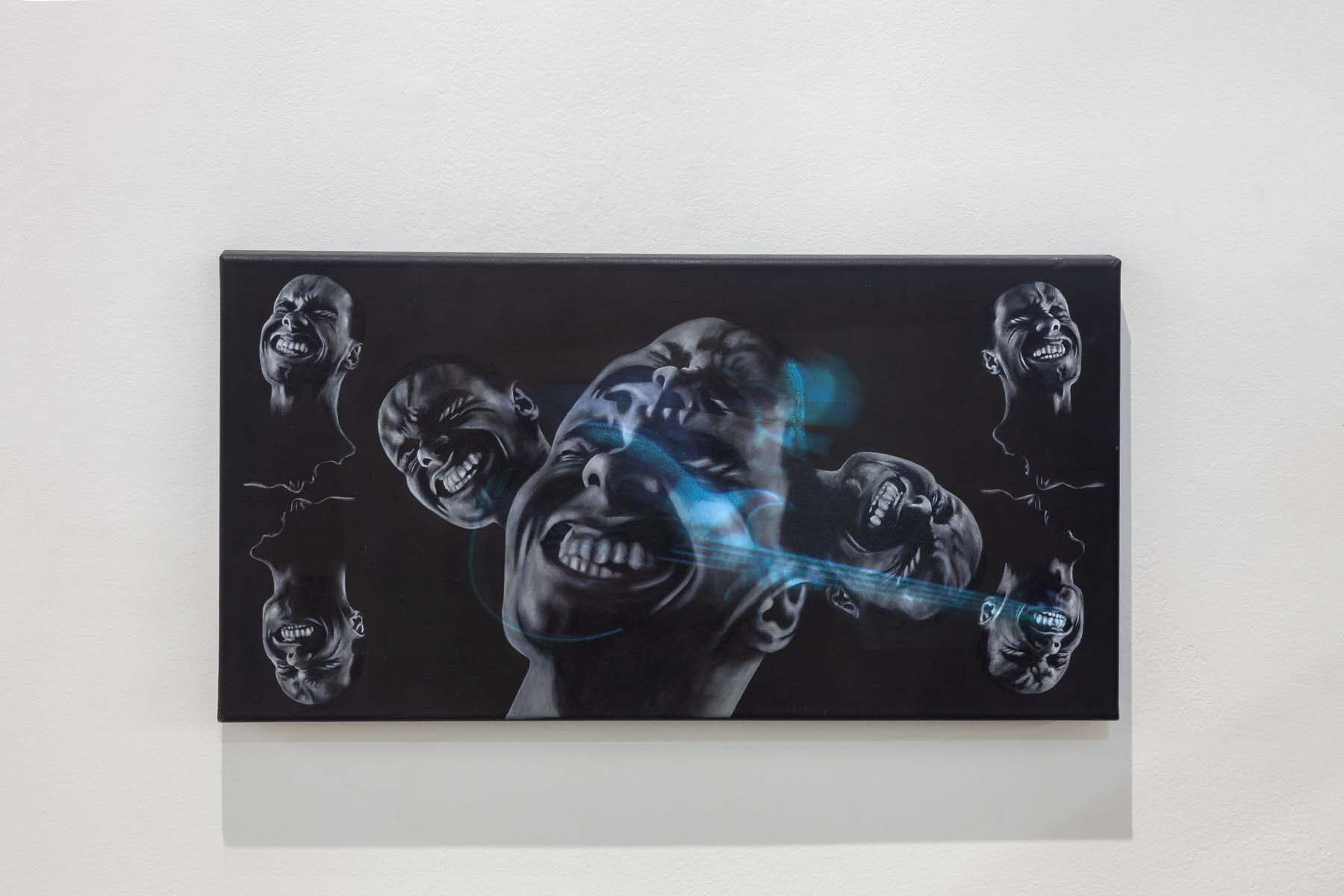

This state of interpretive ambiguity also characterizes the works of Luciana Tămaș featured in the exhibition. Ninnananna (“lullaby”). The exhibition gathers approximately ten of the artist’s recent sculptures, which explore the delicate boundary between everyday domestic objects and instruments of competition or warfare. These ambivalent and questioning objects evoke contrasting sensations in the observer due to their seemingly inappropriate functions and unique construction. Created using recycled materials and DIY methods, the works humorously expose the latent aggressive aspect of everyday objects and banal forms prevalent in our daily lives. Silicone tubes, metal clothespins, luggage trolleys, wood scraps, and fishing rods are amalgamated and rendered ineffective (and playful) instruments of war. Consequently, harmless missiles, wooden machine guns, and faux drones completely incapable of flight, constructed from scrap metal, come to life.

5.

Tămaș’s practice is characterised by the use of DIY and waste materials in assembly and installation, endowing them with a purely symbolic value. Transitioning from the imagery of technological warfare and space exploration, the artist fashions sculptures that, often improvised in form, serve no real purpose. Tămaș presents homemade and harmless imitations of such devices, which lack the exploratory and playful psychological purposes we often associate with toy weapons. These defunctionalised objects, fabricated by the artist, embody real parodies of instruments of conflict in the eyes of the viewer, evoking amusement through their material typology, imprecise assembly, and playful tendency to repurpose previously destined elements. Tămaș deconstructs the imagery of domestic objects, unveiling their ambiguities and darker facets, reimagining an anthropological and anti-militarist variation of Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen. However, in this instance, the artist takes a backseat, allowing the observer to mentally envision the possible actions the improbable objects could undertake.

6.

Tămaș’s works repeatedly incorporate parts of varying origins, each with their unique, discernible forms. This assembly method encourages viewers not to perceive the work itself in its entirety and material singularity, but rather to discern the individual constituent elements chosen by the artist, thereby fragmenting their thoughts. Observers are prompted to project themselves elsewhere, tracing the origins of the different components, their intended uses, and the manner in which they were combined. Consequently, the unity of the sculptural vision is juxtaposed with a rhythmic fragmentation of stimuli. Ultimately, the artist’s works should be understood as hypertext-objects in a broad sense, facilitating the user’s ability to swiftly conceptually traverse the different elements physically connected by the artist. These works are thus devices that enable a multitude of connections.

7.

Tămaș’s sculptures resemble domestic objects in every way, aided by the use of ordinary, low-cost materials that are often irreverently utilized, lacking the characteristics commonly associated with fine art practice. Her sculptural practice is devoid of a quest for grace or preciousness, instead mockingly diverting the gaze towards anthropological critique. These works do not represent or illustrate concepts but rather allude to the limitations of ordinary thought. They serve as revealing tools that caustically underscore the latent, often concealed, potential inherent in the objects and tools of conflict present in our lives and within the intimacy of our homes. In response to their pervasive psychological and tangible presence, Tămaș poses unexpected and impertinent childish questions. As a result, the observer is positioned in a critical, lucid, and playful state, engaging with works that serve as metaphors for a relentless progress bent towards conflict and war, devoid of a truly humanistic technology.

8.

It is challenging to envision a response to the questions posed by the artist, let alone a way out of this predicament. As the exhibition’s title ironically implies, perhaps all that remains is the comforting lull of a tender lullaby.

[1] G. Bateson, Mind and Nature, New York: E.P. Dutton, 1979, p. 139.

[2] G. Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of the Mind, Northwale: Jason Aronson, 1972, p. 139.

[3] See J. Baudrillard, The System of Objects, London: Verso, 1996.