Matteo Attruia

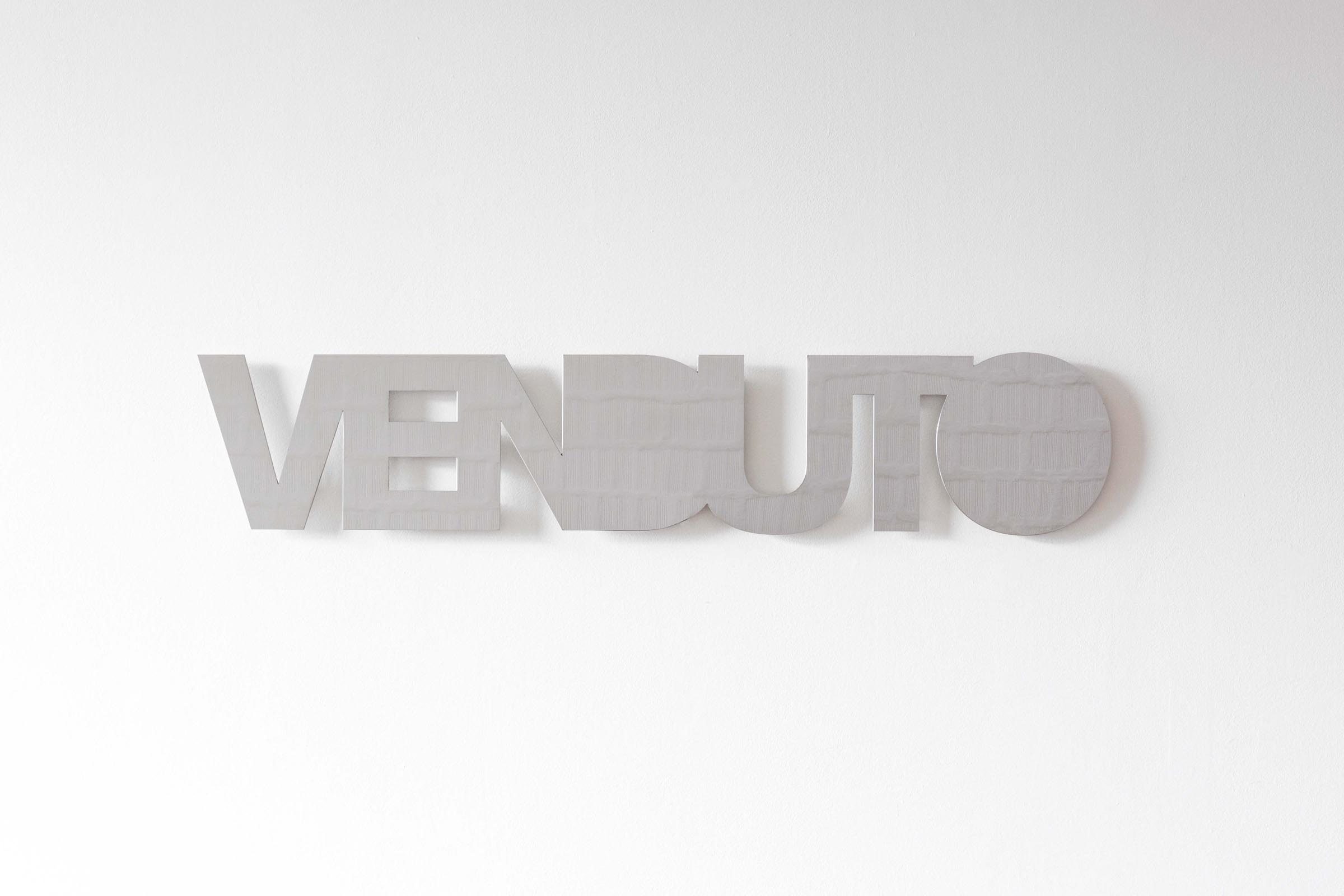

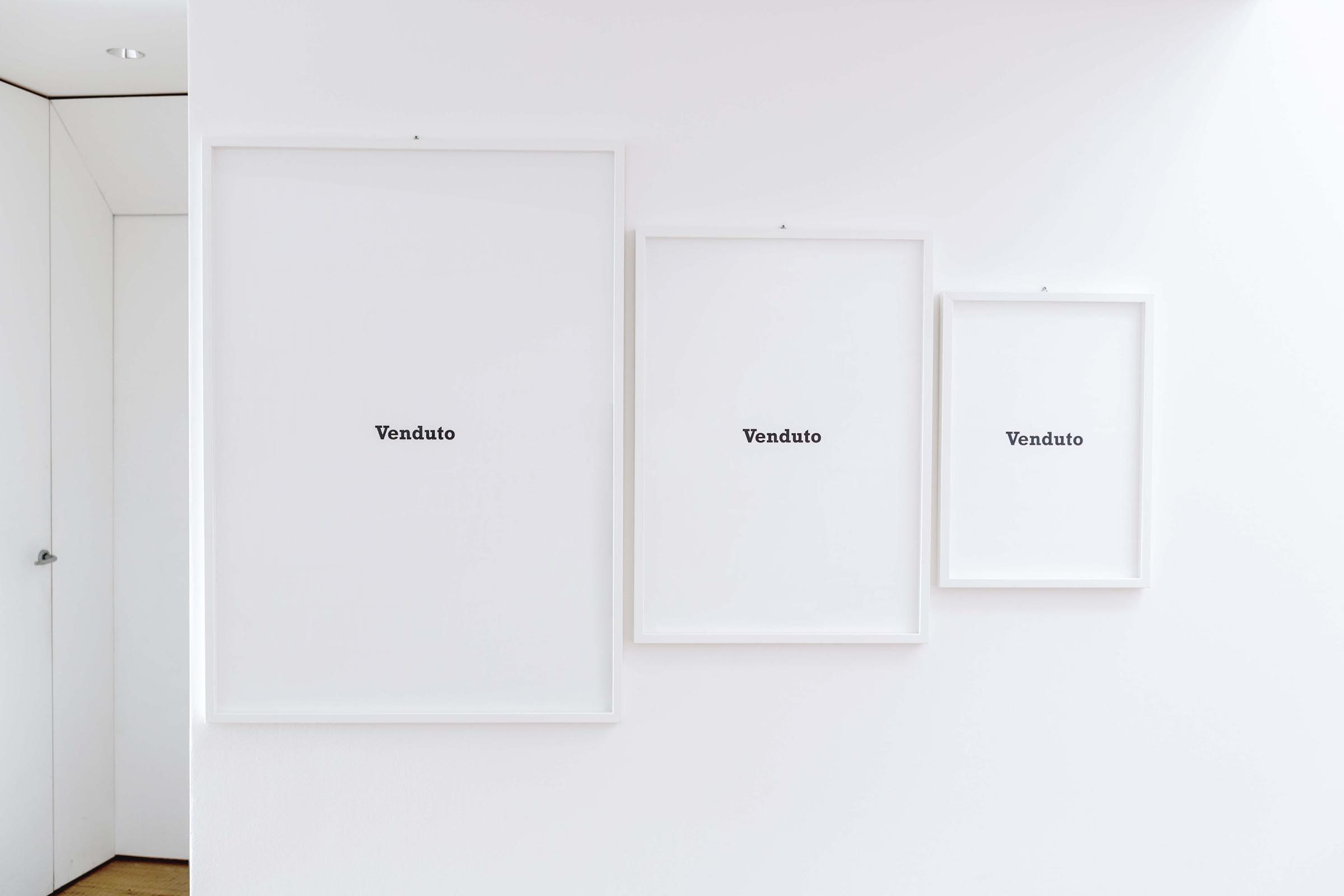

Sold Out

Mestre Venezia (I), Galleria Massimodeluca

October ― November 2018

Atteo Mattruia. Changing the game plan

Daniele Capra

Partially non-argumentative text

Although there are different approaches to writing a critical essay for an exhibition of contemporary art, I have always believed that the argumentative text is the best. It provides the necessary amount of distance from the subject, which the writer is always inescapably entangled with (even if unconsciously). It also provides a crystal-clear Cartesian structure, an architecture that guarantees precision and clarity in talking about the exhibition. Furthermore – I must admit – I am the proverbial dwarf perched on the shoulders of the lessons given by giant? Italo Calvino in Six Memos for the Next Millennium, and at the moment I cannot see anywhere shoulders? that would offer me a better vantage point.

On this occasion, however, I am forced to take a different path. This is partly because of the remarkable relationship I have with Matteo Attruia, but also because, in order to fully understand his research, I cannot help but talk about personal events and experiences that take me light years away from any notion of objective evaluation. In his case (or, rather, in our case) life and professional practice are so close, that they are not only indistinguishable, but also a source of mutual nourishment. Furthermore, there are also undeniable relationship-based reasons that arose when the project for this exhibition took shape in the artist’s head. Reasons that, in the interests of intellectual honesty, I am forced to disclose.

An exhibition without knowing first

One morning in some month or other, I was invited to lunch by Matteo Attruia. Over lunch, he told me that Marina Bastianello, director of the Massimodeluca Gallery which he had been working with since the start of the year, had invited him to hold a solo show in late September or early October. I was happy for Matteo, I knew that he had a deep-seated need to develop a new project, and I felt that in many respects this was the most suitable gallery to bring one of the many projects in his moleskin to life. Also, Marina is a friend of mine, and much more that a person I just have a professional relationship with. So, what could be better than two friends working together on the same project?

Over that lunch, Attruia and I also talked about his need to have a curator to bounce his ideas off for the exhibition, all the more so because the project was particularly ambitious from an intellectual point of view. I recommended two curators that I think highly of, and told him that I would rather not hear anything about the exhibition and its contents before the inauguration: for once I wanted to go to one of his exhibition as a viewer, without knowing – as always happens between us – all about the project, the thinking behind it, the regrets, the second thoughts and the setbacks that happen every time in preparing a solo show where everything must be congruous with the author. He immediately understood my point of view and from that moment on stopped sharing the details of the project with me, although some news was occasionally or inadvertently leaked to me by Marina herself or by Nico Covre (another friend I respect), who followed a part of the project, writing the other text that you can read in this catalogue.

At the end Matteo and Marina realized that there was no need for a curator since the project had been widely shared, digested and developed. However, a month ago, Matteo asked me if I wanted to write a text for the exhibition: he said he felt there was a need for it, perhaps because he had been too daring or perhaps simply to feel less alone. I agreed, on condition that I was not going to talk about the exhibition as such, but instead wanted to consider and reflect on the artist himself, preserving my right to enjoy, semel in decennio licet, an exhibition without knowing anything about it beforehand. However, before moving on to the argumentative part of this text, I must make a confession.

Keep it to yourself

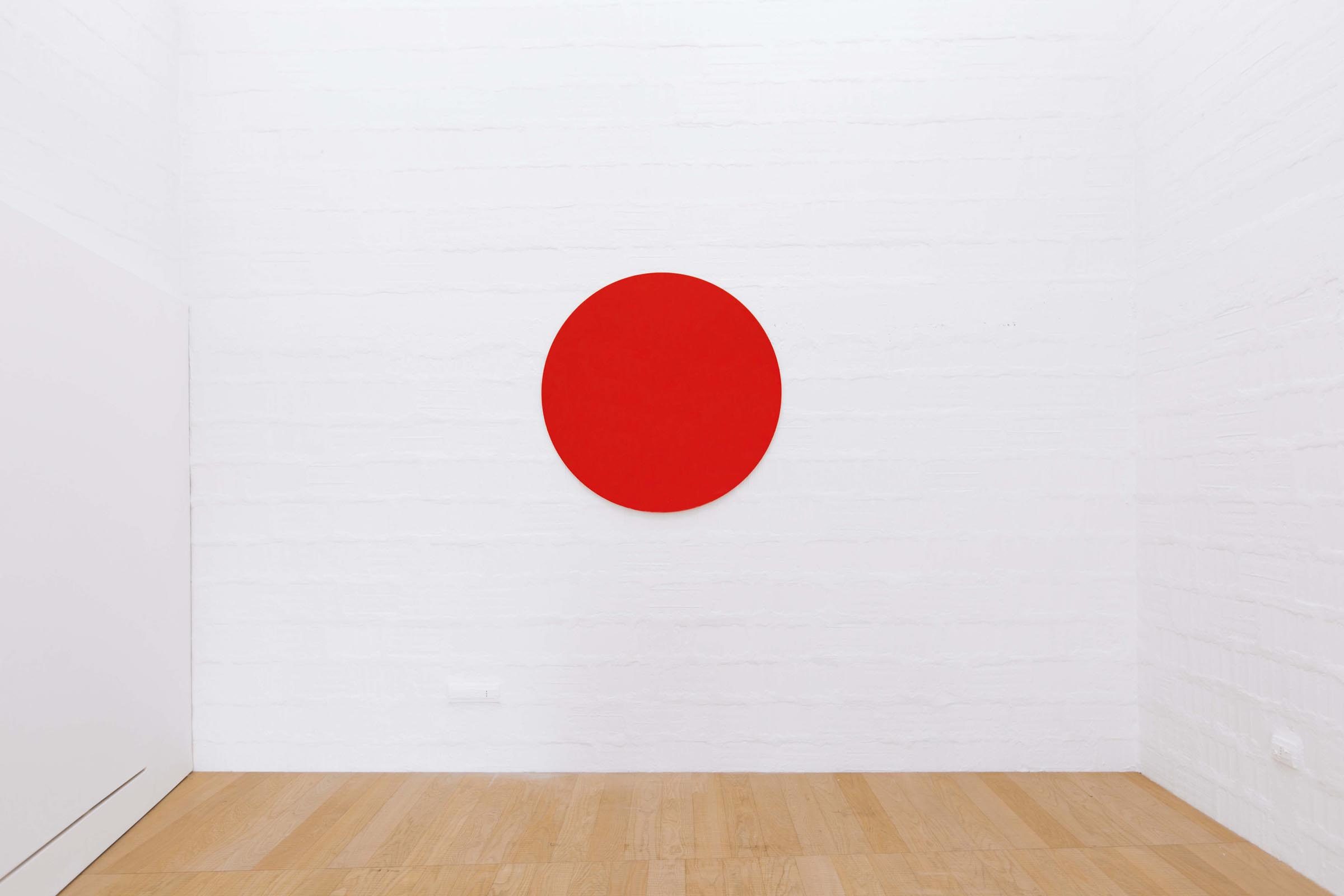

The Galleria Massimodeluca is hosting two concomitant solo shows by Matteo Attruia. Clearly, a single exhibition was not enough to quench the artist’s thirst for exhibiting. So in recent months he conceived an unprecedented and tongue-in-cheek double solo show, or, we could say, a two-artist exhibition with himself. A Flower for Piet and Sold Out were conceived as two different projects, an idea that came from the architectural layout of the Massimodeluca gallery space, which is made up of two distinct rooms, each of which, for the occasion, can be accessed separately, as if the gallery had been doubled. Attruia conceived two distinct exhibitions, each with its own logic in terms of concept and set-up. Two aspects combine in a deliberately ambiguous form: on one side there is the natural ambition of artists to exhibit their work, which Attruia depicts in a self-deprecating way, knowing that he too shares it, and at the same time the intellectual ambition for an incisive and significant project through which to express themselves.

Although I don’t know anything about the exhibition, or only a very general idea of it, I was the editor of the press release for the show, except for the part regarding the exhibition A Flower for Piet. This part was written by Nico, but in a way so as not to reveal the content of the exhibition to me or the visitors. I wrote about something that I did not know, something that I could have made an educated guess about, but that I certainly did not have a suitable intellectual grasp, given the task.

Please keep this confession to yourself. I would be grateful if you did not tell a living soul about it, both because I am a serious professional who firmly believes in his work and I would not like to be thought badly of, and because I hold Matteo’s research and Marina’s work in great esteem. Do you promise?

Outside the gallery

At the beginning of September, Attruia and I met at the gallery with Marina. We discussed some aspects of the exhibition, the timetables, the communication and organizational details, including the work of the press office (Casadoro-Fungher, which has been working with the gallery since its early days) and the set up – which I would not be involved with, because, as I explained before, I wanted to see the exhibition for the first time at the opening.

At the end of the meeting, Marina left us alone for a few minutes and Matteo went out on the terrace to smoke a cigar. I joined him and, seeing him thinking/loiter leaning against the brick wall, I had the idea of taking a picture of him between the two entrances of the gallery. The result was an image that could be an example of the condition of uncertainty faced by the artist, but also of his desire to be the protagonist. The artist is portrayed outside the gallery – that is, not inside where the works are usually exhibited, possibly alluding to an outsider role in the art system – his expression and philosophical stance suspended between the two spaces, seemingly in a condition of existential melancholy, but with the awareness of a possible solution at hand. Like Socrates, and unlike many other talkative artists who claim to be wise, Attruia humbly knows he knows nothing, and he is aware that this gives him a great expressive advantage.

Expectations

I don’t know what the profound subject matter of Sold Out is, I overheard about works to take to the picture framer, but I don’t know if this had to do with this exhibition or A Flower for Piet, as is more likely. In my head, I have pictured an exhibition that is almost bare, which is revealed to the observer only after a few moments, the time needed to put information together. I imagine it to be an anti-contemplative exhibition, in which the works should not be read in detail or for their expressive power, but rather as a (incoherent?) set of works that have something in common, something elusive, not immediately understandable. Elusiveness and unfathomableness are recurring psychological aspects in Attruia’s works, and perhaps also in his character. Frequently his works play precisely on the dissymmetry of information between artist and viewer, so that the latter can unknowingly feel a momentary and pleasant feeling of inadequacy, which then quickly disappears.

I have no expectations about the exhibition, but I don’t think that the works will be positioned in the gallery with any diegetic criterion, since I have never seen the artist show any need for emotional structures or complex narratives: therefore I don’t imagine there is any order, linear organization or climax. I have also wondered whether the exhibition could consist of just a single work, but this would be appreciable only in conceptual opposition to the other exhibition (empty/full).

Over the last few days I also thought that Sold Out, in a reference to Cattelan, may indeed not contain any work at all, playing first on the expectations of collectors and visitors, and then on all the other actors of the art system. I have not made my mind up, and I am enjoying this pleasant uncertainty/doubt until the moment of the inauguration. All I know, is that when everything becomes clear to me, I will have a glass of wine in my hand.

Paradoxes

Matteo Attruia’s artistic research is characterized by paradox and a refined interpretative ambiguity, which is frequently expressed through an ironic, tragic or careless approach. Ambivalence, a polysemy that ceases to be a virtue to become a labyrinth with no way out, is one of Atruia’s most important stylistic devices.

I met Matteo Attruia in 2009, when I was contacted by him for his project for the sculpture competition held at Villa Manin: on that occasion he had asked artists and professionals from the art system to suggest a work to propose for this project, since he did not consider himself up to the task. My curator friend Guido Comis had told me about him, but I did not know his work and I had only met him occasionally, as a visitor at some exhibition or other. At that time I also received a ransom style letter from him which he had put together using newspaper letters cut out and glued to a sheet of tissue paper, like in seventies detective stories. The content of the letter was this: “Dear Daniele, if you know what’s good for you, you should organize an exhibition of Matteo Attruia’s work, quickly!” It probably also included the name of the blackmailer (the artist himself) who would benefit from the exhibition, which, theoretically, could also have brought an economic advantage to the person being blackmailed. There was no clear threat in the letter: what would have happened had I not complied with the request?

In fact, this note was actually a gift of an artwork (another element that contradicts the factor of possible damage that occurs with a threat) and paradoxically a call for attention, care or direct engagement. It was, in the first place, a way of claiming recognition or a place, even a small one, within a system to which he was not certain he belonged. It was an interrogative attitude addressed to those who already had a role. An anonymous letter containing a tongue-in-cheek threat is a ploy that Attruia has used, frequently and with not entirely disinterested generosity, with collectors, gallery owners, curators, museum directors, and also simply with friends.

He has used paradoxes as a ploy before, such as with Vendo oro (“I sell gold”), signs made with the cheap graphics of pawnbrokers shops offering to buy gold (which alludes to the work as a precious material produced by the artist and to his own condition in society), and particularly Courtesy of the Artist, in which the artist takes up a chisel to engrave on the wall the writing that provides the name of the work. This is a work in which the artist gives something to the collector (the artwork) by actually appropriating one of his walls, which is damaged by his actions. Many of his works put the final recipient in the condition of being a prisoner trapped in an unsolvable contradiction. Straddled between cunning and naivety, between friendly and disturbing, in a state of uncertainty, oscillating between being happy and feeling mocked.

Humility

The question of feeling adequate or not, which is different from actually being up to the task, is one of the most significant intellectual – and existential – themes in Attruia’s work, and the one which has produced the most abundant results. A Franciscan kind of weakness, the humility of those who feel that their skills and abilities are not up to the task. When this is embraced, it becomes a strength. Not only does it lower the expectations and aggressiveness of others in a competitive situation, but it makes it possible to take advantage of the generosity and skills of others (for example friends, neighbours, colleagues, etc.).

Being humble and asking others allows you to share your work, your doubts and, in part, your successes. It is a sort of postmodern, shared form of authorship, in which the boundaries between the self and others must be negotiated and established from time to time, without it causing any particular concern. In this way, humility is an important relational weapon. Properly used, it promotes collaborative processes and causes the artist and their role in society to be seen not so much as a remarkable individual that stands out from the ordinary, but as a cheery circus acrobat on a unicycle, who will invariably drop the balls he is juggling.

Humility arises from self-irony: it is a way to make fun of yourself, to reconsider your position and your ideas in a non-rigid and non-self-referential way, with a softer, more compromising approach. Matteo Attruia has no God complex, and if he ever entertained the idea, it would be to describe himself ironically, and with noble detachment, in even lower terms.

The words

The use of written words is a recurring feature in Attruia’s art: neon words, luminous signs, commemorative plaques, road signs. In each instance, the artworks are not endowed with their own original aesthetic quality, but take on the graphic characteristics and sizes of items that already exist and have a function. It could be said that the use of the word he chooses is overlaid onto the reality of objects. It creates in some way a non-ordinary paraphrase, which is the result of lateral, derivative or deviant thought. For example his work Bau Bau, in which the famous sans-serif Bauhaus sign on the main building of the Dessau design school, is corrected by doubling the “bau” part. This doubles the verb part of the name: in German “bau” means “to build”, but in Italian it sounds like the generally accepted transliteration of a dog barking and also evokes “babau”, i.e. “bogey man”, the imaginary monster that is used to scare children.

All his poetics is strongly characterized by a linguistic element, which can be traced back to a refined literary dimension, partly due to the artist’s eclectic literary taste. Attruia is a voracious reader: his home library, as well as being an unconscious monument to himself, could also be considered a sort of alter-ego in paper form. I have often jokingly taunted him by inviting him to knock it down, saying that Carmelo Bene claimed that books should be written and not read. Even if things you own end up owning you, as Chuck Palahniuk cautioned, this rarely happens, as literature fortunately gives you the freedom of following non-linear paths, and to re-discuss the role and expectations of the reader. Certainly literature, also in a metabolized form with its surreptitious effect on thought, has been a constant intellectual and existential source for the artist, who, not surprisingly, has had the portrait of various writers tattooed on his body.

Craftiness

Those who are cunning are defined in the Cambridge dictionary as “clever at planning something so that they get what they want, especially by tricking other people, or things that are cleverly made for a particular purpose”. Attruia’s work is cunning in this way, we might say doubly cunning: in relation to himself as an artist, because he manages to find a way to untangle even the most unimaginable situations, and if there is no way, he knows how to pretend to have found it anyway; and then in relation to the viewer, because he shows and elucidates some of the deceptions that appearance, ordinary thinking and slavish respect of the gnoseological hierarchies can hold for us. As in basketball, if the game plan doesn’t work, you need to change it.