Nebojša Despotović

Velvet Gloves

Trento (I), Galleria Boccanera

November 2010 ― January 2011

Painting as Timing and Precision

Daniele Capra

Such isms as modernism, postmodernism etc, they’re just no longer applicable to the world we live in. The whole practice of painting is about two things: timing and precision. [I]

Never as today has painting been such a choice for those artist who practice it. An empathic choice that has only been laterally influenced by the great development of the media, technology, and telematics which have – more than anything else – implemented the number and efficiency of the working tools as well as the way in which social relationships are managed. But there have been no epochal changes in the dynamics with which painting is created and produced, given that the artists who devote themselves to it are in some way naturally impelled to an intimate and daily hand-to-hand fight with it: given that painting is nourished by innumerable stimuli, many of which are far distant from its own world, manual ability and technique are unavoidable factors because artists construct their own identity by the act of working. Due to this continuative and constant personal relationship, paintings show, not only their ideological, cultural, and aesthetic background – as with all works of art – but also the physical stratification of the work that the artist has finished: in other words, a brushstroke sums up in itself the history of all the brushstrokes made because it is the total outcome of all the additions set down by the artist. It is, therefore, inevitable that painting highlights a past condensed on the surface and with respect to which the artist needs to make a résumé; he is obliged to do so (even in the moment when making a minimalist work or having a non-objective or procedural approach) in a form that is quite often compulsive and violent, not so much in his particular way of painting but in the pressing need to work. Jean Luc Nancy has written, “the image is the prodigious force-sign of an improbable presence irrupting from the heart of a restlessness on which nothing can be built. It is the force-sign of the unity without which there would be neither thing, nor presence, nor subject. But the unity of the thing, of presence and of the subject is itself violent”.[II] The result is that painting further raises the pressure by adding to its charge the image it produces, an evidently cumbersome adoptive daughter.

Nebojša Despotović’s work is, in many ways, the result of this combined action of daily work, pressure, and intensity which do not acknowledge each other reciprocally yet are evident, above all, in his way of following his interests and controlling their outcome. When visiting the studio of an artist it often happens that you see works of varying quality, and frequently what is most stimulating is the ability of the curator or dealer to intuit the strength of the works and choose those that are most stimulating. On the various occasions that I have been in Nebojša Despotović’s studio I have always been amazed by the quality of all his works; basically, there was nothing to be put aside or was less intense. On the contrary, all the works were fascinating. Like Bacon, the artist himself made a first choice through a kind of intelligence that is not so much a question of self-censoring but of selecting (“I destroy many works but the best remain”). So it seems that, apart from expressive and linguistic impulses, behind each work there is an intelligent kind of responsibility related to Richter and his wish to leave his mark on the world because “a painter has to believe in what he does, he must be completely involved in what he is doing in order to be a painter. Once he is obsessed by it he will come to the point in which he believes he can change mankind through his painting”.[III]

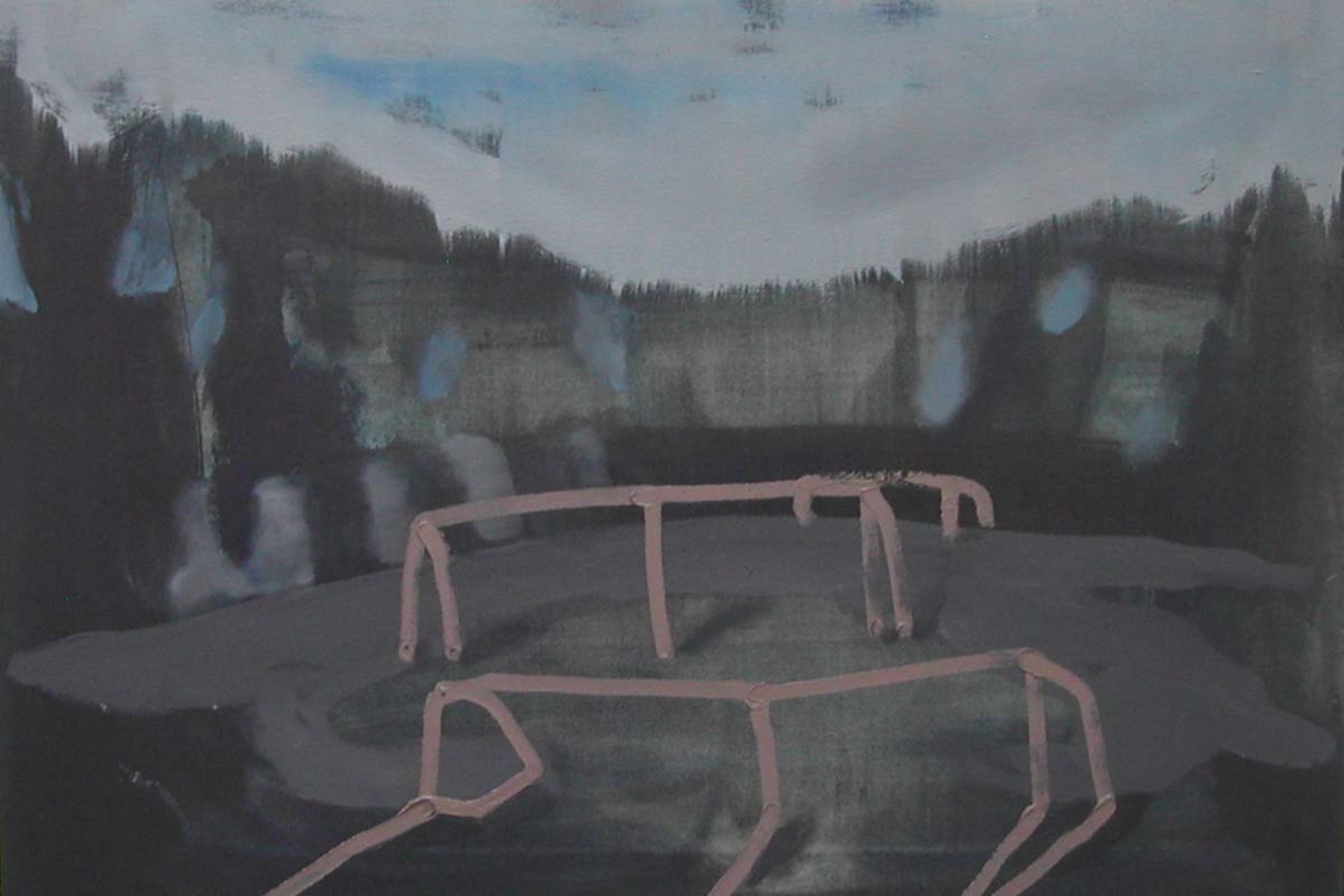

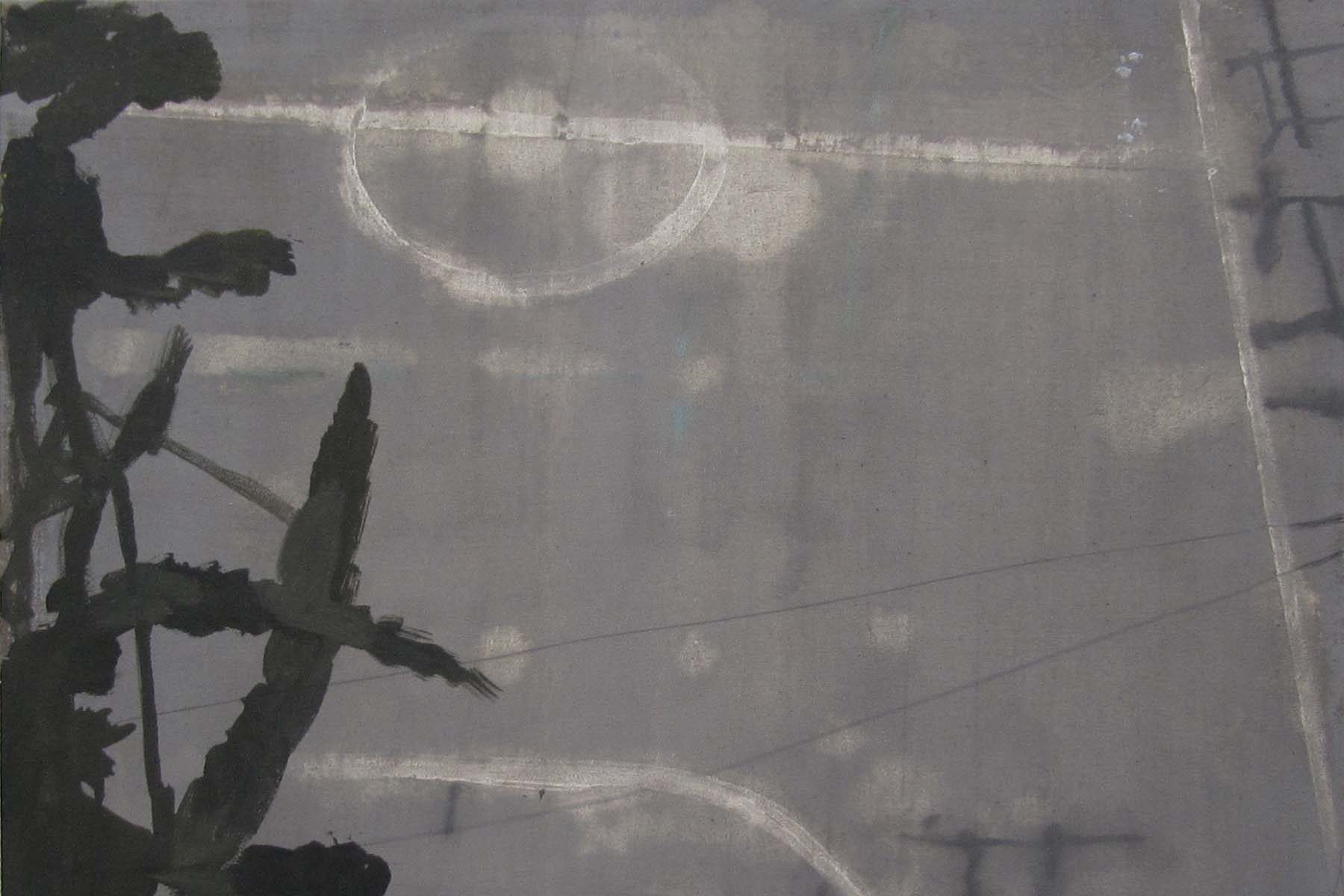

The works grouped together under the title Velvet Glove are the result of Despotović’s activities based on memory and on particular and individual hoards of photographs. This is a series which started from a project for working in an iconographical and technologically recognizable way, one in which, apart from the worth of each image, there are close relationships between the works. To evolve and invent single series rather than individual works allows, on the one hand, a concentration of energy yet, on the other, requires an elevated form of intellectual self-control. Or, as this Serbian artist says, “I am crazy about Richter’s work. He manages to make each brushstroke an element of a far greater mechanism”. So we can already appreciate his aim of building a basis for large-scale works.

The Velvet Glove works are characterized by a particular approach to the history of individuals, and their aim is to bring to the surface images, situations, scents, and sensations which would otherwise be buried for ever in the drawers of old chests. Spontaneously, the forms of this young artist have the power to allow the emergence of pieces of a forgotten past, as happened with Proust’s madeleines. In fact, the works result from a hunt for images that has its beginnings in history books, old photos, old encyclopaedias, and schoolbooks picked up in flea markets. They are slices of abandoned personal memories which end up in the hands of people distant in time and space; and yet there is nothing in common between those who look at the images and those who are portrayed. They are never icons but, rather, precise identities. These are people who have lived, fought, loved, and suffered. Their distance from us is indicated by the yellowed paper which represents the wear of time and the draining away of their iconographical value. And so his work, without ever being a weary ode to the past or of what might have been, allows the visual concentration and condensation of what time speedily dilutes. The men, women, and children whom, having saved them from oblivion, Despotović portrays in the poses they assumed in front of the camera, tell us of a world that no longer exists and that by now is firmly a part of the mare magnum of history. Yet they were probably never protagonists or recognizable protagonists of this history. But their new portraits are testimonies to the importance of their (and our) individual existence, of all that it is necessary to fix on and keep hold of for future history. Never so much as since the 20th century (when the masses became part of history and the media became central to our society) have we been able to say, even at an iconographical level, that we are history.

The dull, leaden colours, the dark yet feisty tints (from which we can intuit the artist’s love of Tuymans), the heavily underlined yet never completely defined physiognomies, and the barely sketched-in details, all allow us to glimpse what is most important for us: our own identity. At times this might overlook some bits and pieces because we are not moulded by the hands of anyone, least of all by an artist such as Despotović who does not claim to explain everything and who knows perfectly when to silence his brush. And so he manages to show what is not clear or perfectly outlined. An element hidden among the folds of our life or the wrinkles of a velvet glove which, unknowingly, is held in the hand of a child seen in an anonymous portrait.

[1] L. Tuymans in Why Paintings Succeed Where Words Fail, interview by G. Harris, The Art Newspaper, September 2009, p. 38.

[2] J. L Nancy, The Ground of the Image, New York: Fordham University Press, 2005, p. 23.

[3] G. Richter, H. U. Obrist, The Daily Practice of Painting, Notes 1973, Cambridge: Mit Press, 1995, p. 78.