Richard Loskot

Open System

Trento (I), Galleria Boccanera

November 2012 ― January 2013

Life is unlocked

Daniele Capra

A Question of Adjectives

“Open” and “closed” are two contrasting expressions usually used to highlight states and situations in which a judgement is implicit on the part of the user. To “have an open mind”, for example, usually means to have a sensitive and curious approach to novelties and events and describes those who have been attracted by the possibility of questioning their own conventions/convictions. On the other hand, we are used to call people “closed” if they are basically uninterested in what happens outside their own world: if, that is, individuals are not very curious about, or uninterested in, discussing, their own conventions/convictions.

If we exclude those cases where “closed” means “protected” or “concluded” ( as well as the cases of sectarian, technical, and slang variants of language), in Indo-European languages there are no uses in which the adjective has a positive sense; it does not, in other words, express a value judgement that is different from what we expect culturally (Italian speakers should compare the note under the heading “chiuso” in the Dizionario etimologico della lingua italiana, edited by M. Cortelazzo and M. Zolli, Bologna, Zanichelli, 1999). In other words, what anthropologically underlies our linguistic system is that the concept of openness is a desirable value, one to be aimed for, and that the notion of closure, on the contrary, is culturally – and, all things considered, from an economic and political point of view too – less remunerative.

So it is not a simplistic and creaking mythology that makes us consider the value of openness to be desirable, but an anthropological and philosophical inclination that numbers among its modern roots some of the theories elaborated during the Age of Enlightenment, the idea of democracy itself, and the concept of the other as the bearer of novelty and new visions of the world.

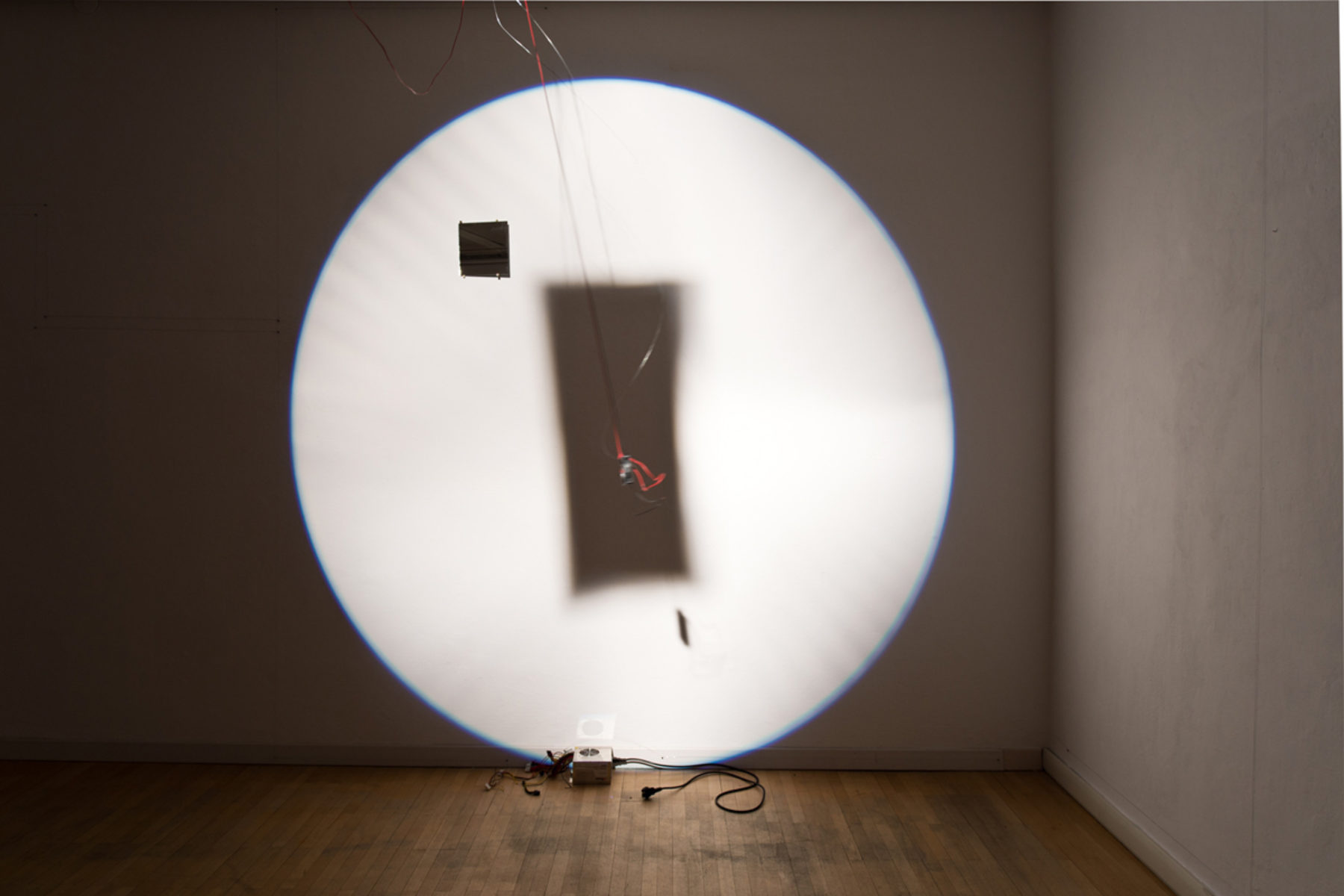

Open System

In systems theory, a system is open if it interacts with the environment, in other words if the input or the effects of the processes that occur within it are conditioned by the action of the outside environment. Basically, an open system does not act in isolation, apart from interactions with external variables (as would happen with a Leibnitz-like impregnable monad), but instead it is subject to the continual effects of the context, to the constant exchange with everything that surrounds it. The input/output dynamics are, then, characterized by a greater complexity because the external variability is such as to influence the system itself.

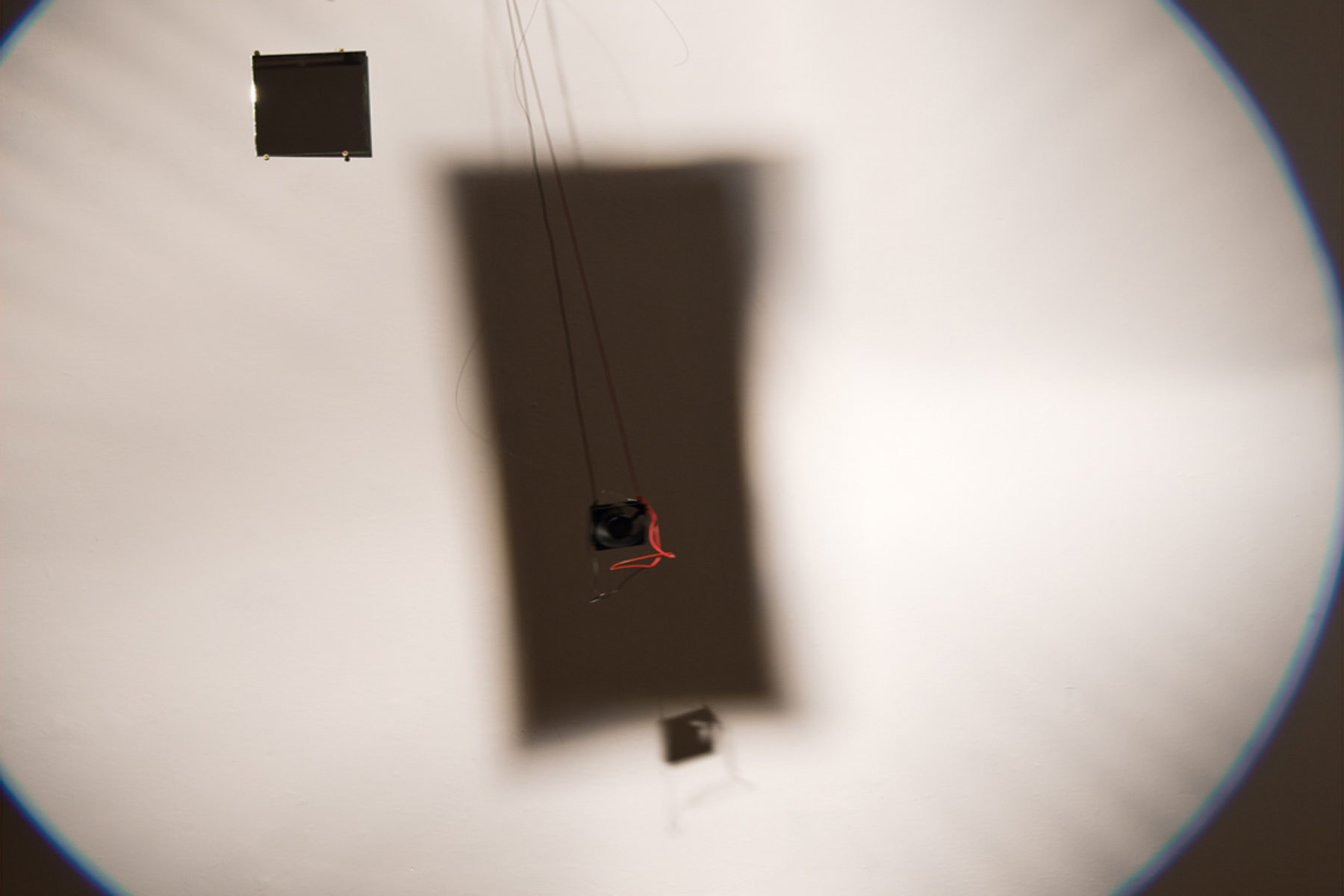

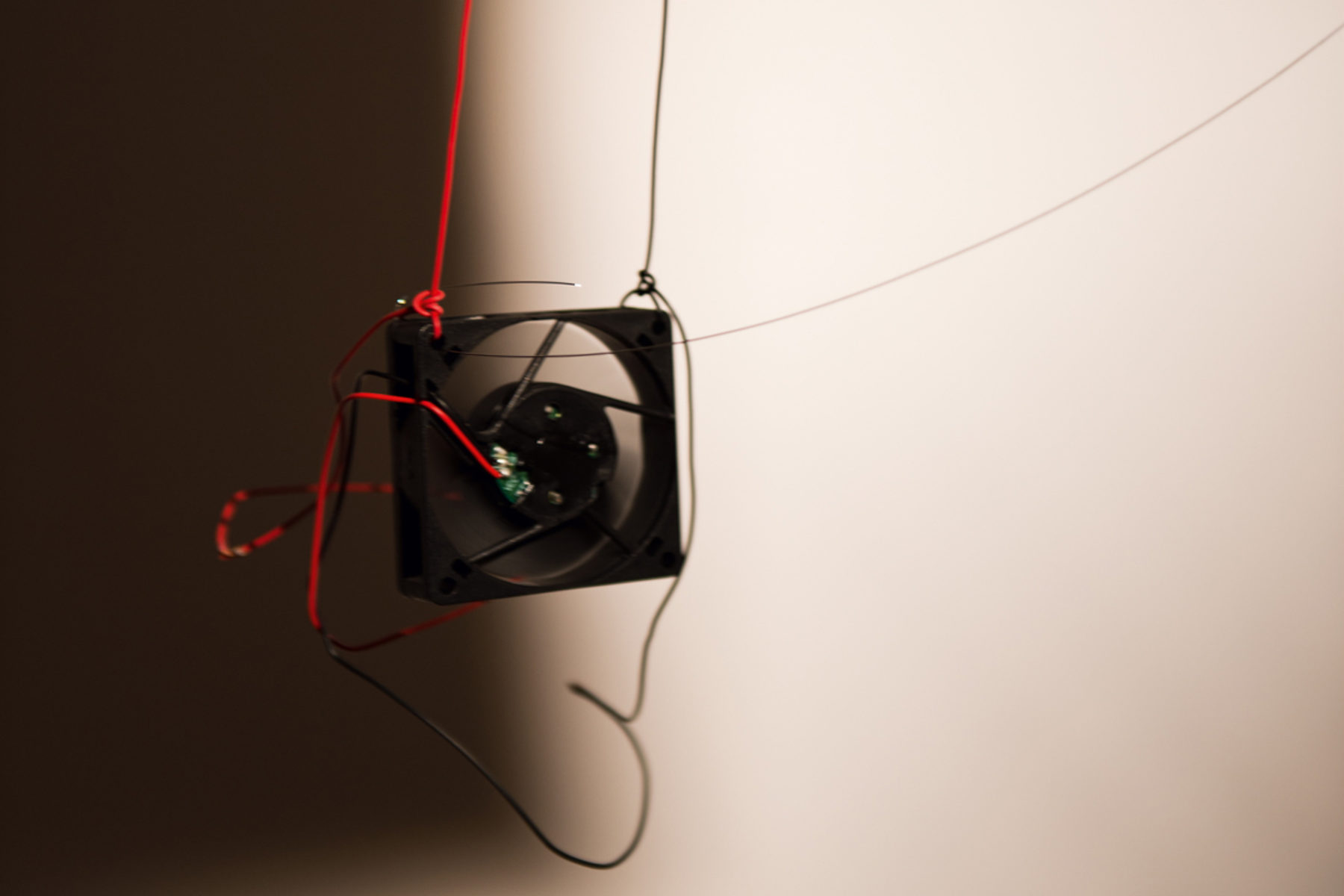

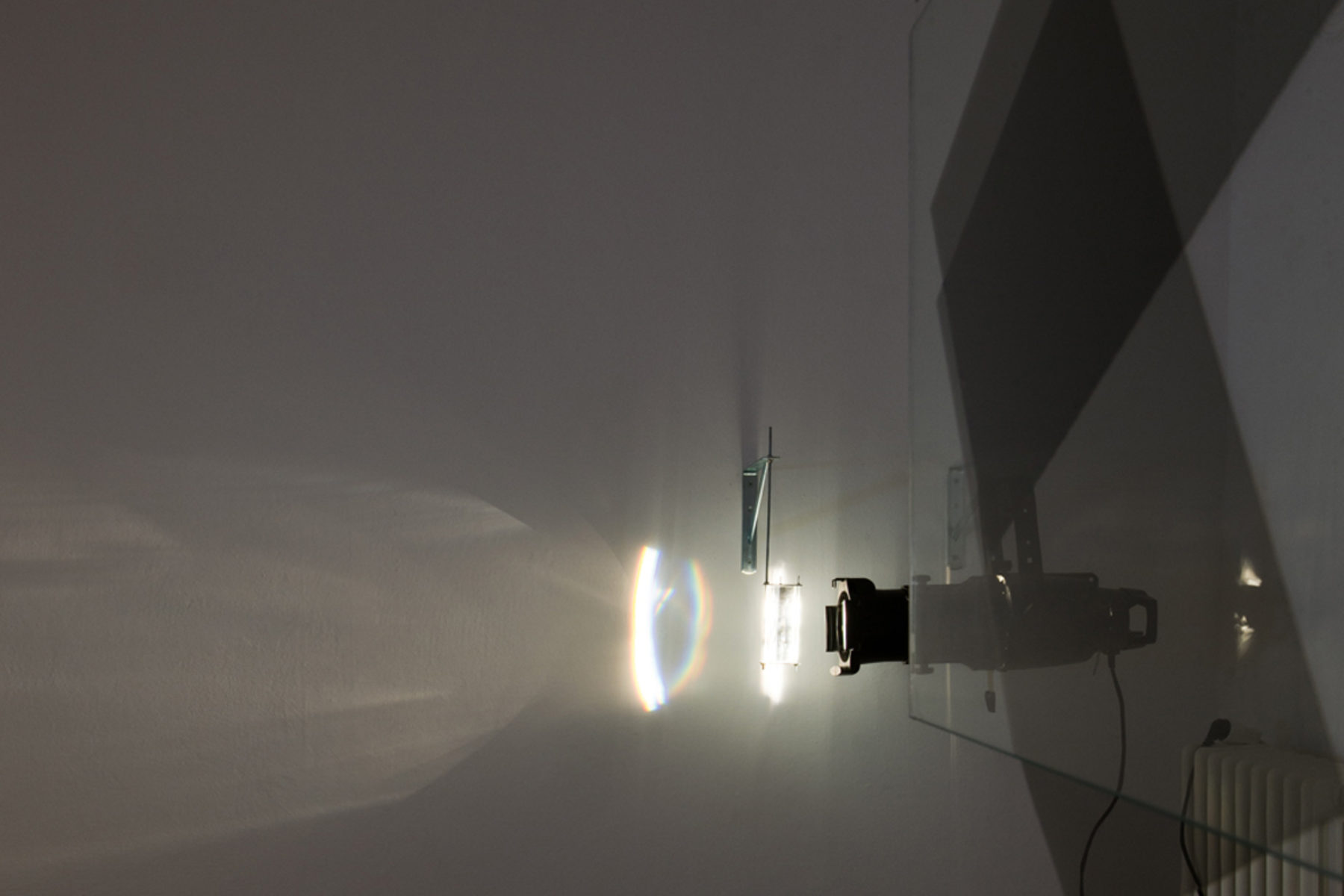

This is the condition we see in many installations by Richard Loskot which frequently result from an analysis of the interactions between the environment, natural light, radio waves, and electronic devices in general. So the variables that make up the work are not only those put into play by the apparatuses that it is physically constituted from, but there are also constant relationships with the context which give the work’s state further possibilities. For example, the presence of greater or less light, the presence of radio waves produced by transmitters or by nearby mobile phones, make the installation a system that adapts itself to the changes in the surroundings. If we push such characteristics to their extreme, we can say that, in regard to the context, a work such as that in the gallery behaves essentially in the same way as a living being because it influences it and is influenced by this context.

We must not, however, confuse such dynamics with the first-hand interactivity between the viewer and the work. In the case of Open System, in fact, there is no direct interaction with the viewer, as happens in other of his installations in which the presence of people explicitly acts on the work. The openness of the device is, in other words, essentially due to the place: the gallery is no longer a container but a space that influences the work and conditions its very structure through the quantity of light or the temperature.

A Delaying Technology

At the heart of many of Loskot’s works is the knowledge that our relationship with reality is mediated by individual perceptions and by the continual imaginative (re)constructions that our senses constantly elaborate. The artist, that is, highlights an empirical/experiential attitude in the face of nature, and technology basically has the scope of reducing the velocity of perceptions and so make them rationally visible thanks to a delayed dynamic for enjoyment.

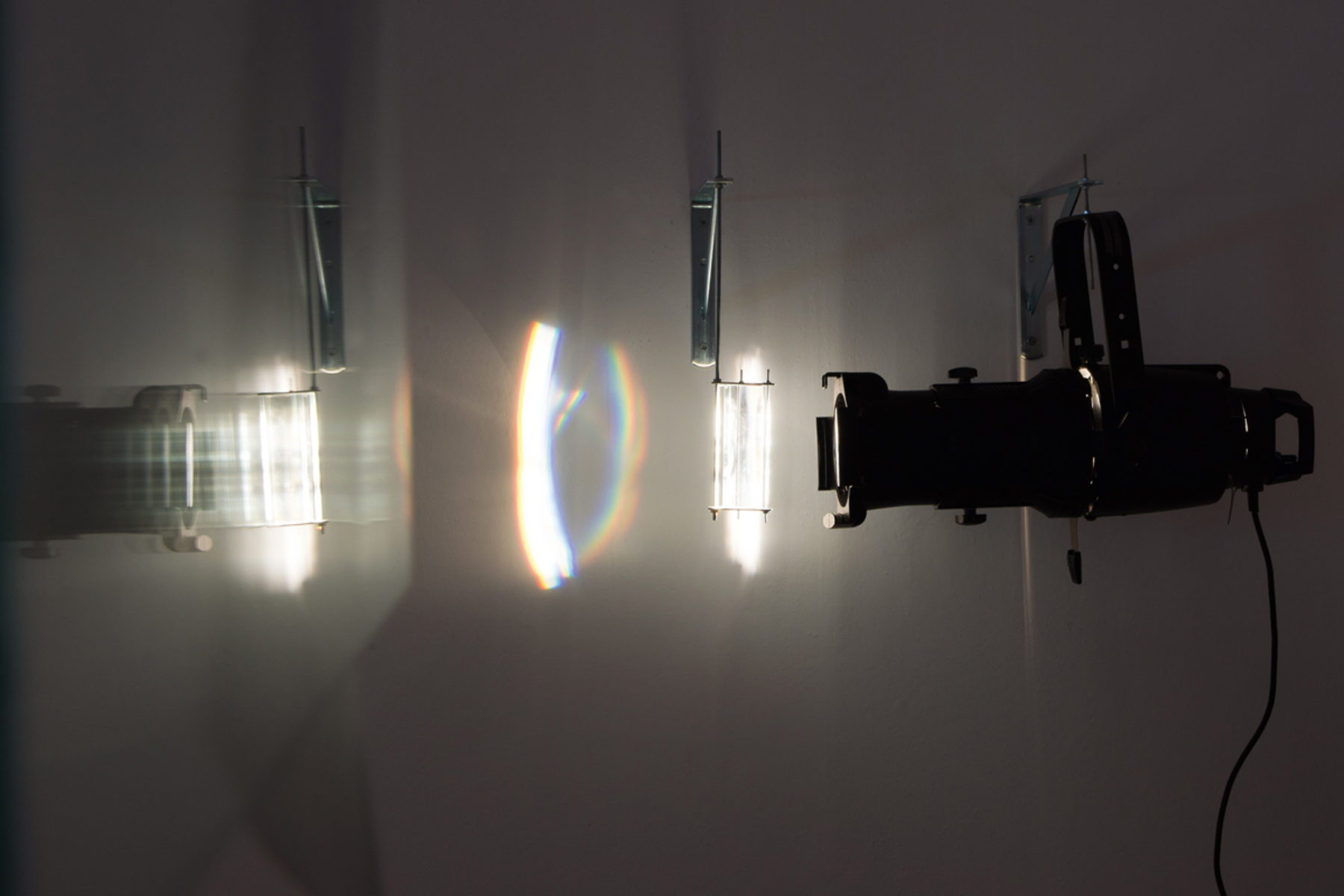

Open System begins in the gallery’s entrance hall which is then connected to the other rooms inside by an unusual leitmotif: a ray of light, reflected from a mirror, guides the viewer through the other rooms and becomes the trigger for an unpredictable process in which our perceptive systems are stimulated. In fact, in Open System the technology feeds and sustains a complex sense-device in which art has the role of surprising and exciting the viewers, putting them into contact with what is most precious to us all: the sense of wonder.

So the phenomena studied, many of which are natural, are a field of inquiry with respect to which technology has only the auxiliary role of an instrument for revealing/manifesting: in other words, it acts like acids do with respect to a latent photographic image which, however, is already imprinted and is potentially present on the paper.

In Loskot’s installations the use of technological devices is aimed at changing the viewer’s immediate perceptions, from the spatial volumes of the environment to the very idea of time itself. For this Czech artist, technology is the factual/concrete tool that in a Promethean-like – i.e. concretely knowable – way makes visible what is hidden from view: it serves to reveal those unexpected phenomena that make reality a constantly replenished reservoir of surprises.

Open Your Eyes

We can say that, thanks to this functional technological approach, Loskot tends to recompose the two polarities of nature and technology to show that it is we who, thanks to art and our senses, sew back together a dichotomy that perhaps no longer even belongs to us. Our senses are precisely suited to collecting and channeling information, to holding together in a single complex perception the Socratic evisceration of the phenomena that the works presents.

For Loskot art is, above all, a sense device; one that, without relying on special effects, generates a surprise by revealing to us what we could never have imagined. The first and deepest impression that we register, once we trust in our eyes, is that of wonder.