Teresa Mayr

I don’t want to be an onager

Trieste Contemporanea Award

Studio Tommaseo, Trieste (I)

May ― September 2020

Daniele Capra

Life is a line, thinking is a line, action is a line. Everything is a line. [1]

Inside the world

Drawing is an artistic practice that is done horizontally to the world by immersion in a visual context, both when it is performed from life, i.e. in the presence of the subject, and in a free, imaginary or design expressive form. On the contrary, painting is usually done vertically and by selection, by isolation or confinement; whereas sculpture (or performance) originates from deambulation, rotation, movement in space. Drawing is stasis instead, it is a silent sum of continuous syntheses made by graphic lines on a surface. In other words, its method is strictly additive, incremental, starting from blank, from vacuum. As Manlio Brusatin wrote, “in the beginning there is a line on the horizon, where before there was almost nothing. And then there are top and bottom, right and left, front and reverse, beginning and end: the encirclement of our own vision.” [2] In other words, drawing gradually creates a visual horizon that is added, overlapped and crossed with the one we are immersed in. A visual horizon that can conceptually order, arrange, create a further order, and set up a system of relationships. Therefore, drawing is a practice that extends reality because it actually expands the semantic field of the context, it extends its triggering potential, thanks to its simplification of the background noise, to its very synthesis.

Background and lines

Drawing creates a relationship between the part covered by the stroke and the paper, which must necessarily remain (at least partly) empty. In fact, drawing means not only scraping a surface with an instrument that leaves a trace, but also being aware that the surface shall remain white in many areas. As Walter Benjamin sharply pointed out, “The graphic line marks out the area and so defines it by attaching itself to it as its background. Conversely, the graphic line can exist only against this background […]. The graphic line confers an identity on its background. The identity of the background of a drawing is quite different from that of the white surface on which it is inscribed.” [3] Thus, drawing leads to the semantisation of a part of the surface, but its effects extend also to the part not directly affected by the intervention: in this way the background itself bears a meaning, as a counterpart of the graphic line, without actually undergoing any direct action. Drawing is a form of negotiating visual, psychological and expressive relationships between graphic lines and their background. The first character is visible and speaks on stage because it was “written” directly by the author, the second instead is silent, present conceptually but in absentia, because it gives space for the other character’s words to be pronounced and heard.

Revelation and history

Painting is a medium of concealment, as it enables the author to restore previous states of the work, to cancel or hide what is underneath (under a painting often lie unfinished works, as art history shows); conversely, drawing is a practice of revelation and search for the “truth”, since it keeps track of all changes on its surface, of regrets, uncertainties or attempts. It is as if it revealed to the viewer: “Every step I have taken in my life has led me here, now.” [4] Drawing is, by its very nature, a revelation, an epiphany of itself, since it shows the history of its identity, its middle phases, its evolution stages, the scars of all the struggles that led to its final state. It is in fact unidirectional in time, and its history is in full view, easily comprehensible.

Teresa

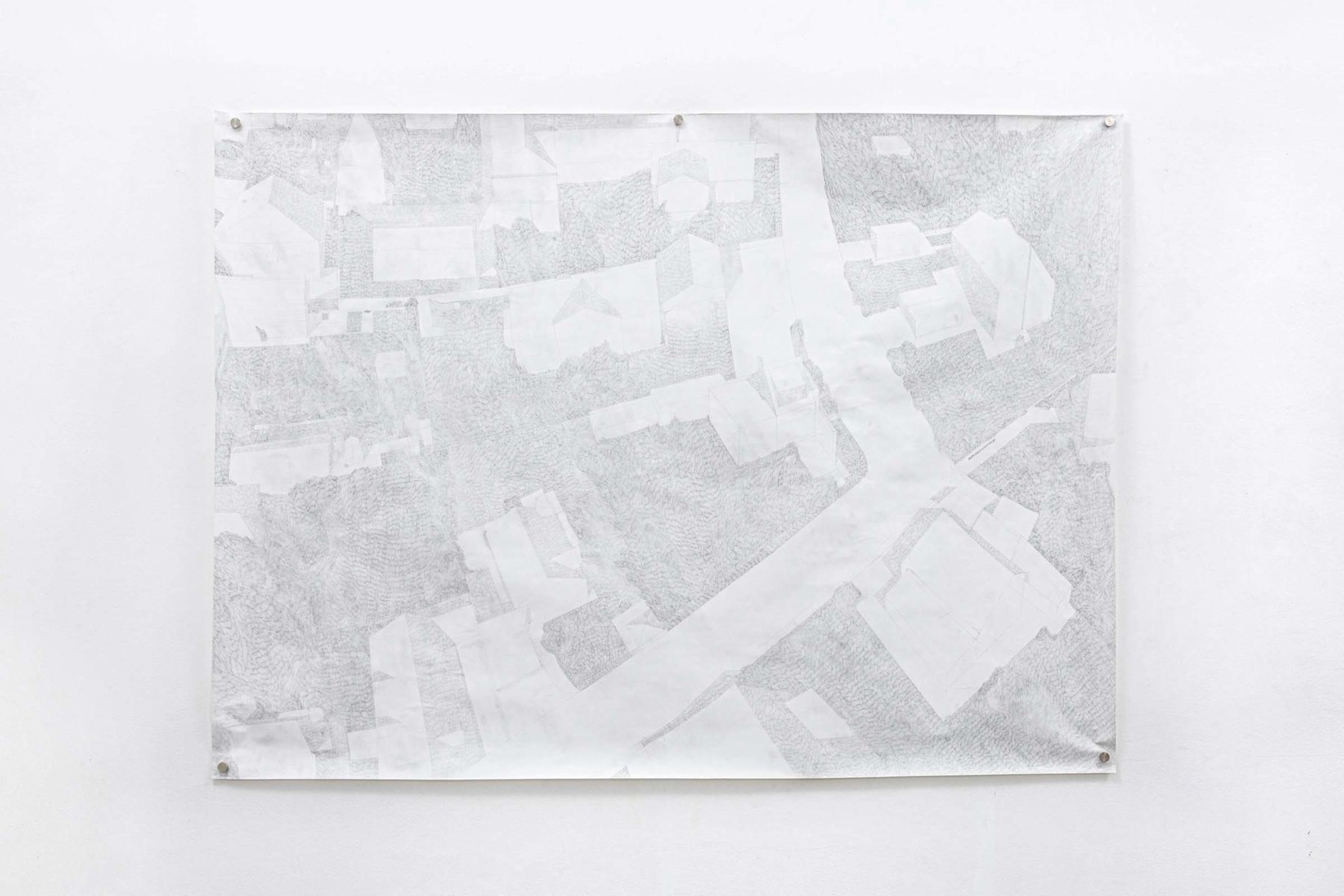

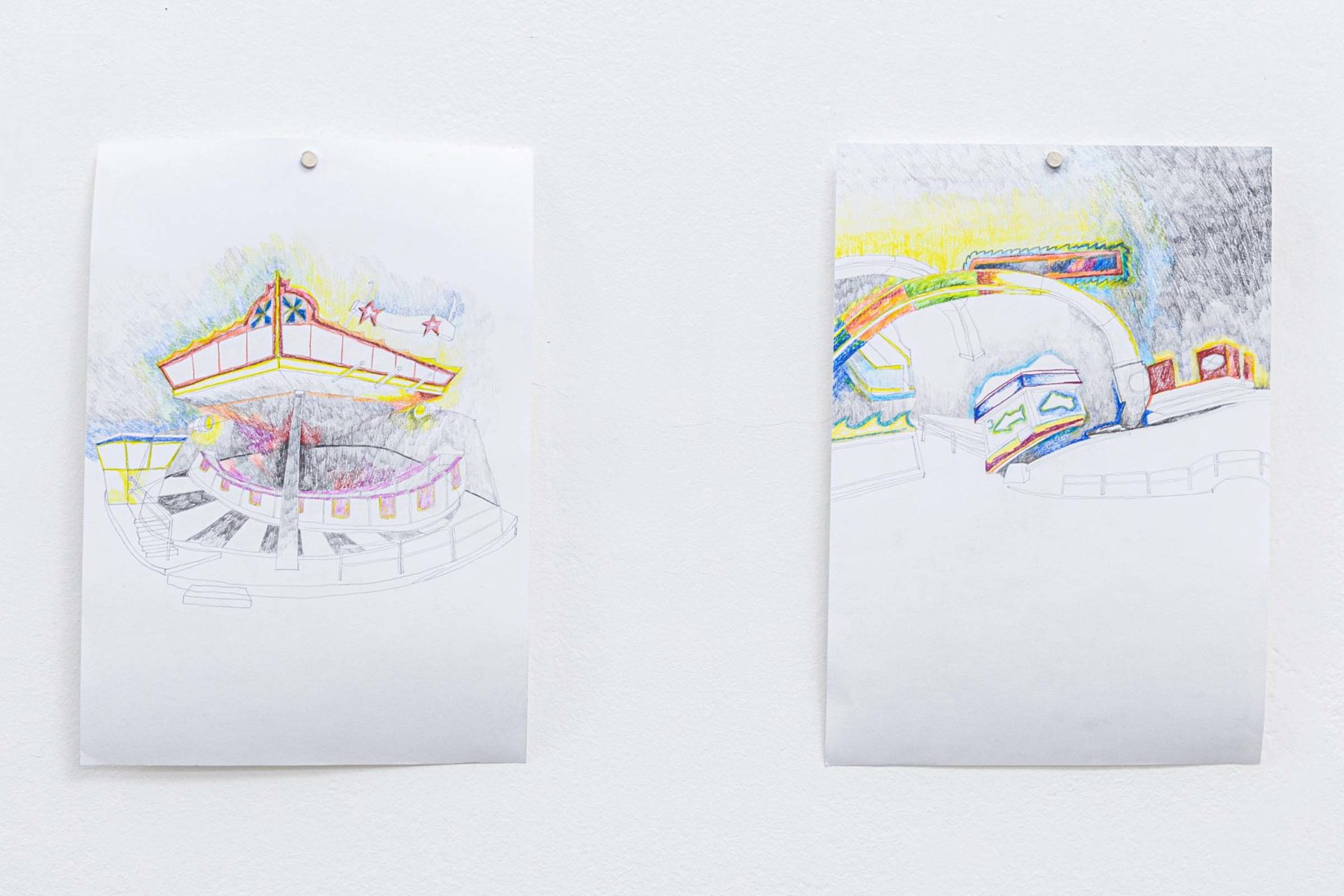

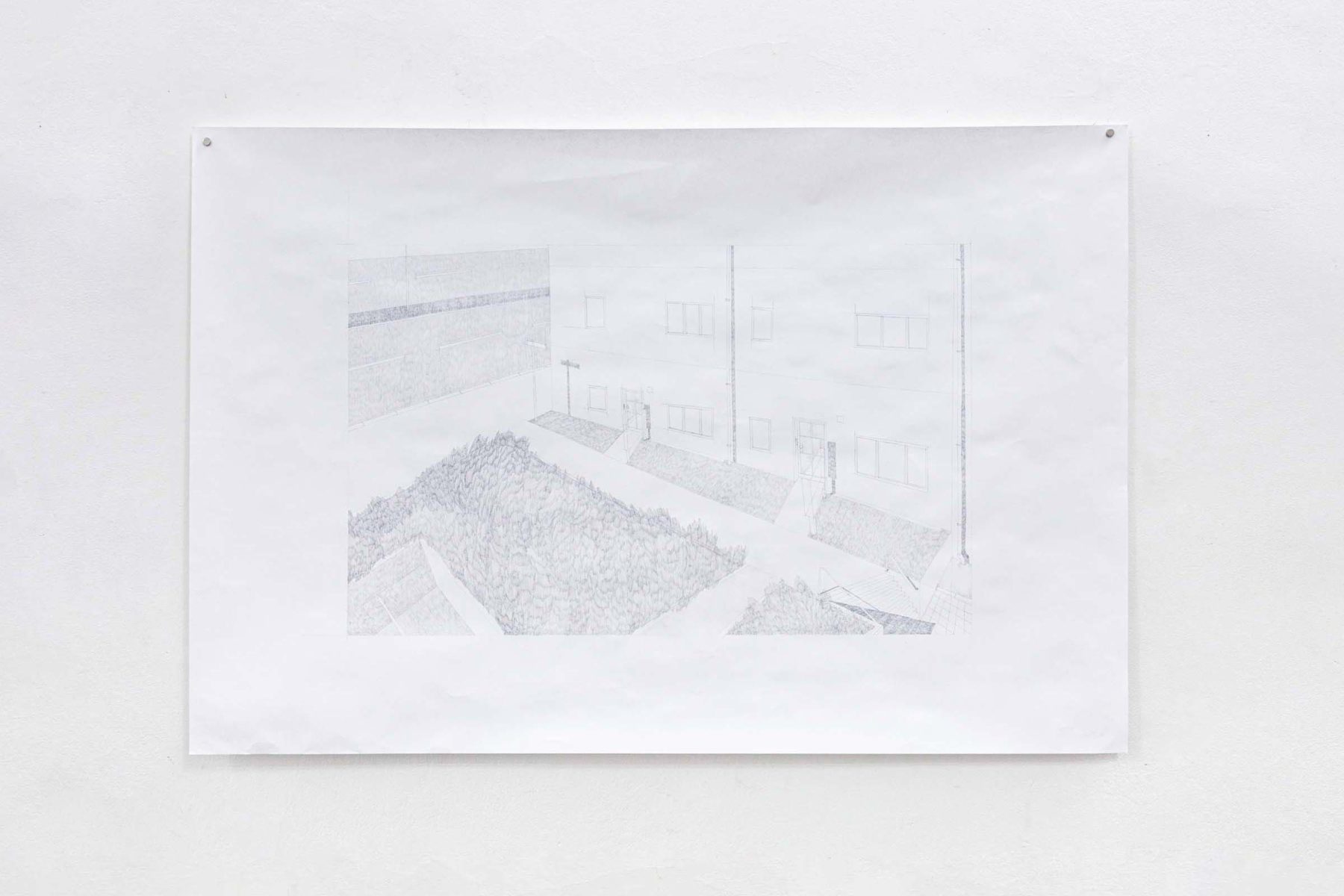

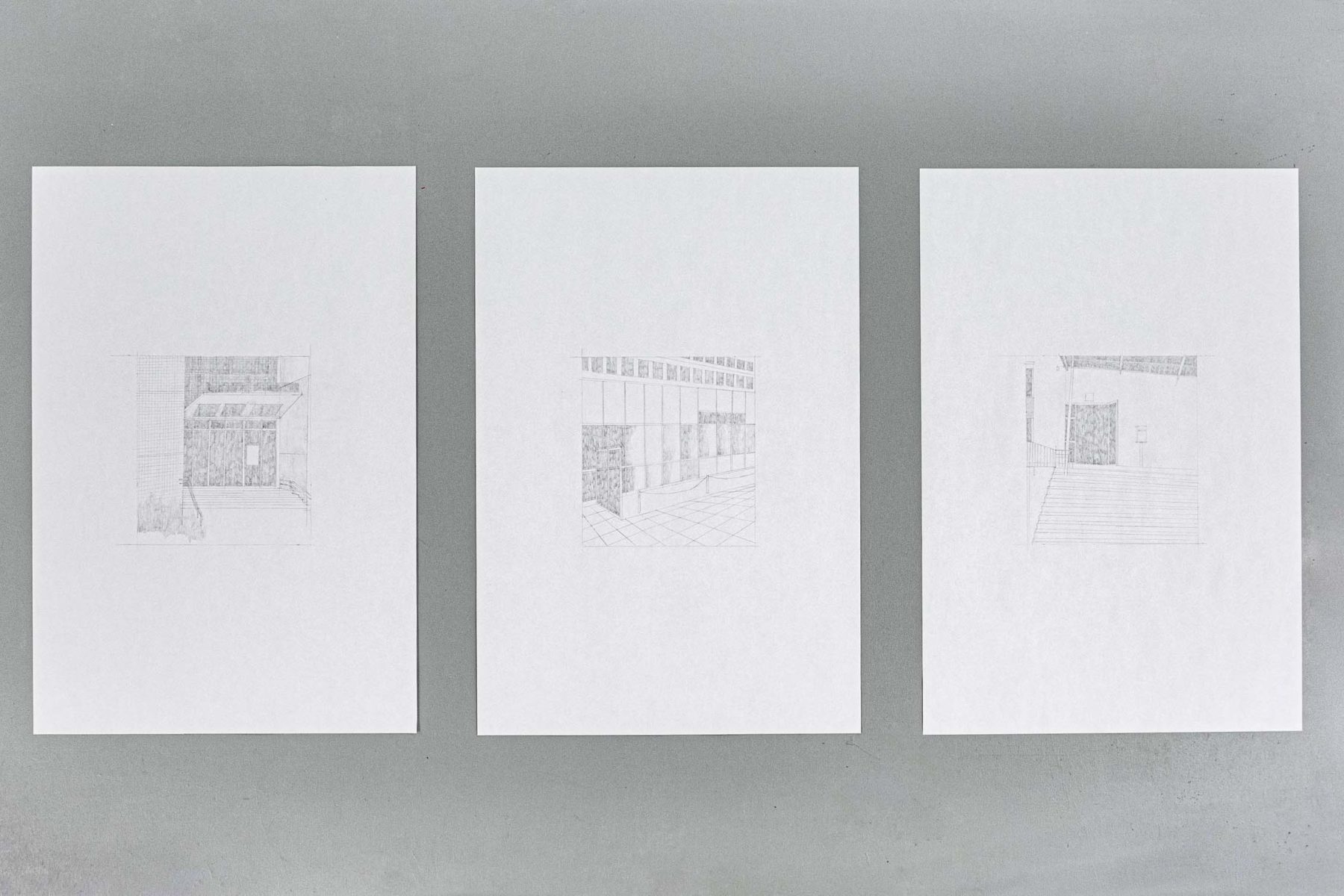

All this occurs to me, when I look at Teresa Mayr’s work. I think of her being inside the world as her work deals with cities (real and invisible ones) and border areas between intimate and public spaces. I think of unraveling pencil or felt-tip pen lines on the surface, in the silence of the white paper which is gradually inhabited by gray or coloured marks, in a state of extreme rarefaction. I think of her revealing parts of an urban context in a Cartesian form, where everything is comprehensible and each element counts equally, with no hierarchy among the marks on paper.

Then I think of immediacy, of the considerations made on paper by mixing real situations, places that exist or existed, with fragments of imaginary cities. Considerations that change continually and are built upon during the act of drawing, since, as Richard Serra said, “Anything you can project as expressive in terms of drawing – ideas, metaphors, emotions, language structures – results from the act of doing.” [5] Therefore, in Mayr’s work there is no distance between thinking/imagining and the act of drawing, since the latter originates the former: intellectual reasons and expressive functions are intimately and ontologically contained in the act itself. Drawing is ultimately a practice that includes considerations about itself: it is self-conscious and self-reflective.

But when I look at Mayr’s works, I think of her imaginative and anarchic style, on tiptoe. I think of the combinations of graphic lines that dialogue with each other on paper and ambiguously show themselves, when the light is grazing, or deny themselves, when instead the surface metallically reflects the graphite. Yet it is almost impossible to see the drawing as a whole, for its numerous elements and plentiful details. Despite the synthetic terseness of architectural design, actually details require a careful and always partial observation, since there is no hierarchy in the composition, in the lines or in the chiaroscuro: graphic lines spread on paper by syntactic coordination in a freely paratactic form.

Essentiality, intimacy, border

Mayr exclusively use drawing, which is minimal also in the tools she employs. Pencils, colours, markers, plain paper: there really is no need for anything else, because the unnecessary is totally superfluous. Such discipline enables the artist to concentrate on creation, on thinking, which occurs and reveals in the act of drawing, that in this way records the primary visual elements, the essence on the surface. This process has a double level of intimacy: one due to the technique of execution, since the drawing results from an extension of the arm close to the artist’s body; and another referring to the subject, to the artist’s interpretation of urban phenomena through a continuous visual investigation into streets, sidewalks, parks, gardens, shops. These are the border areas between the personal sphere and the public one, between what is personally shaped by the individual and what is instead managed by the city, its authorities, the market, nature or even chance. Mayr’s work analyses the different functions ascribed to places, the emotional ties that define their familiarity or strangeness, i.e. respect, indifference or neglect. Her drawings mark the transformation of urban spaces, the traces of their evolution as well as the changes and micro-changes that affect places where the functions of individuals and citizens overlap and intersect. The city, the urban dynamics and the socio-economic situation are not mere backgrounds or contexts in which something happens, they are rather actual subjects.

Samples

For her works Mayr uses real samples of the urban area, that she makes either in person walking downtown or looking for images on the internet, social networks or Google Street View (which offers often obsolete views, despite the increasingly dense mapping and the tighter control exercised). These sources are compared and then recombined by the artist, who is in search for the probable middle stages or is figuring their potential evolution. Real images are mixed to their probable memory or their potential future: realistic fiction and reality interpenetrate and merge, so that “many lines grow and become an orderly wall of stones, a living or dead city.” [6] Hence, drawing gathers the effects of all anthropological, psychological and socio-political variables, but at the same time records the expectations or the will for a possible change, and becomes an unexpectedly political, critical, proposal or “conflict management” [7] tool.

[1] M. Brusatin, Storia delle linee, Torino: Einaudi, 1993, p. 22.

[2] M. Brusatin, Op. Cit., p. 10.

[3] W. Benjamin, Selected Writings, Volume I, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996, p. 83.

[4] Here I borrowed the title of one of Alberto Garutti’s most important works, which actually has no direct relationship with the act of drawing. Tutti i passi che ho fatto nella mia vita mi hanno portato qui (“Every step I have taken in my life has led me here, now”) is a writing on stone embedded in the pavement so that all passers-by can read it. This work, with a vague existentialist mood, has been installed by the artist in different urban contexts in Europe since 2004 and is a metaphor for the complexity and stratification of our lives.

[5] R. Serra, in L. Borden, About drawing: an interview, in Richard Serra. Writings, Interviews, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994, p. 53.

[6] M. Brusatin, op. cit., p. 13.

[7] These are the words Paweł Althamer uttered in our conversation when he was working at his installation Draftsmen’s Congress, at the 7th Berlin Biennale in 2012.

A conversation between Daniele Capra and Teresa Mayr

Let’s start from the very beginning. How did everything start? When did you decide to be an artist?

I spent my entire childhood drawing, painting and building. The question for me was rather how or what kind of artist I wanted to become, except for a brief period when I wanted to become a marine biologist. By the end of high school my plan was to become a stage designer, but when I started that class at Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, I realised that I would rather do fine arts. So I immediately changed the focus of my studies and switched to the painting/drawing class.

Drawing is now your favourite medium. Usually drawing is less complicated and faster than painting, since you don’t need a studio or a specific place to do it, and you only need paper and some essential tools as pencils, pastels, pens, etc. For centuries in the Western tradition drawings have been intended just as artists’ sketches, notes or drafts, while in your case they are fully finished artworks. How has drawing become so important to you?

It is precisely these factors, the immediate, minimal and intimate aspects of drawing, that are so appealing to me. I am also interested in the question of painting in drawing: can a drawing become painting? Why is it not, when do the boundaries blur? I examine this issue especially in my more recent works, in which I use crayons and felt pens. Another reason why drawing is important to me is its sustainability: low effort of materials, easy storage and transport.

Often painting is based on the chance for the artist to do/undo/redo some elements or even the entire work. We can imagine painting as an adding-and-removing practice, as a walk in which you can go further and come back to the previous location. Drawing instead is straight and faster, since the artist cannot return to a previous step, as an intense and quick short run. Do you like working with this attitude? How do you combine the speed of drawing with the intimate feelings you deal with?

My pictures are created through a process. There is no concrete plan of (spatial) construction or arrangement. So this fast and straightforward working process requires above all acceptance, which usually excludes the need to turn back. The reality I perceive – including feelings – means to me a contingent combination, consisting of a multitude of possibilities. Comparable to the way a Rubik’s cube works, except that no monochrome surface is created and that the number of small sub-cubes is infinite.

Would you list your main interests?

Art, rare animals, philosophy, black holes, true crimes, urban development and architecture, theories in general, cinema, theatre, bars and, of course, my new Rubik’s cube!

In your research you usually mix all these disciplines, as the ingredients for a dish. In my opinion architecture and urbanism are the most important, as they deal with more intimate fields like spatial awareness, psychology, housing or privacy. Do you consider your work as a political practice?

My work handles the influences that the environment has on people, how it shapes them. I focus on changes and decisions, especially in urban spaces, which inevitably affect the movement and behaviour of the individual. In this respect the subject of my drawings is highly political, since it is about nothing less than controlling and influencing the design and functionality of (public) spaces and shaping society as a consequence.

Cities and the society in general are the result of negotiations among different interests, attitudes, ideologies, private and collective histories. They are expected to be the heaven of diversity, but we know they are not so, because, even if we live in a democratic system, the power is not well balanced and changes are too swift to be easily governed. How can your practice help the viewer to understand these issues or manage the citizenship process?

When you look at my work, you usually see nothing unknown. However, the sceneries I build remain unused and deserted. Functional places are deprived of their purpose. It is easier to question the supposedly self-evident and necessary. If you use an escalator, you will probably think that it goes too slowly, too many people are on it, bump into you. On the other hand, if you’re waiting on a platform all alone and the empty escalator keeps rolling towards you, rolling away, rolling towards you, it’s almost spooky; it may seem like a hungry animal, a construction somehow unnatural, absurd. I want to create the awareness that an escalator, to stick with my example, is a possible principle that was designed, but actually it is not a fixed part of the ground we walk on. If you understand this, structures and systems (of society) seem more fragile and changeable. This perspective can encourage to change things, not to take things too seriously, not to let yourself be overwhelmed by them.

In a broad sense I think that deserted houses, streets, gardens or shops without people are just unfulfilled useless projects. There’s a sharp contrast between the clean pencil or colour lines and the empty minimal background. Don’t you feel there’s someone/something missing or melancholic?

Yes, they are useless. This is what should make us think: that such large parts of our cultivated, civilized planet are useless if they are not used by humans. Thinking the other way around, this proves our questionable, anthropocentric approach to the world.

In this context, I find melancholy feelings downright welcome!

How do you choose your city views? How do you combine in your artworks your personal experience, as a citizen or pedestrian, with more anonymous and impersonal views you find on Google or on social networks?

The pictures I find online have a similar function to that of the structures in public spaces. Digital platforms standardize subjective or personal image material in form or content, just like the physical public, space and infrastructure are organized. In my drawings I merge this supposedly objective view with my own perspective and memories into fictitious, constructed images. The working process is very intuitive and fluid.

In your works houses are uninhabited, shops, spaces and gardens are empty. Human beings and animals are missing or maybe somewhere else. Why do you choose to hide their presence?

Because it is not about humans…