Marina Marković

The Arrangement(s)

Salon, MoCAB, Belgrade (RS)

June — August 2024

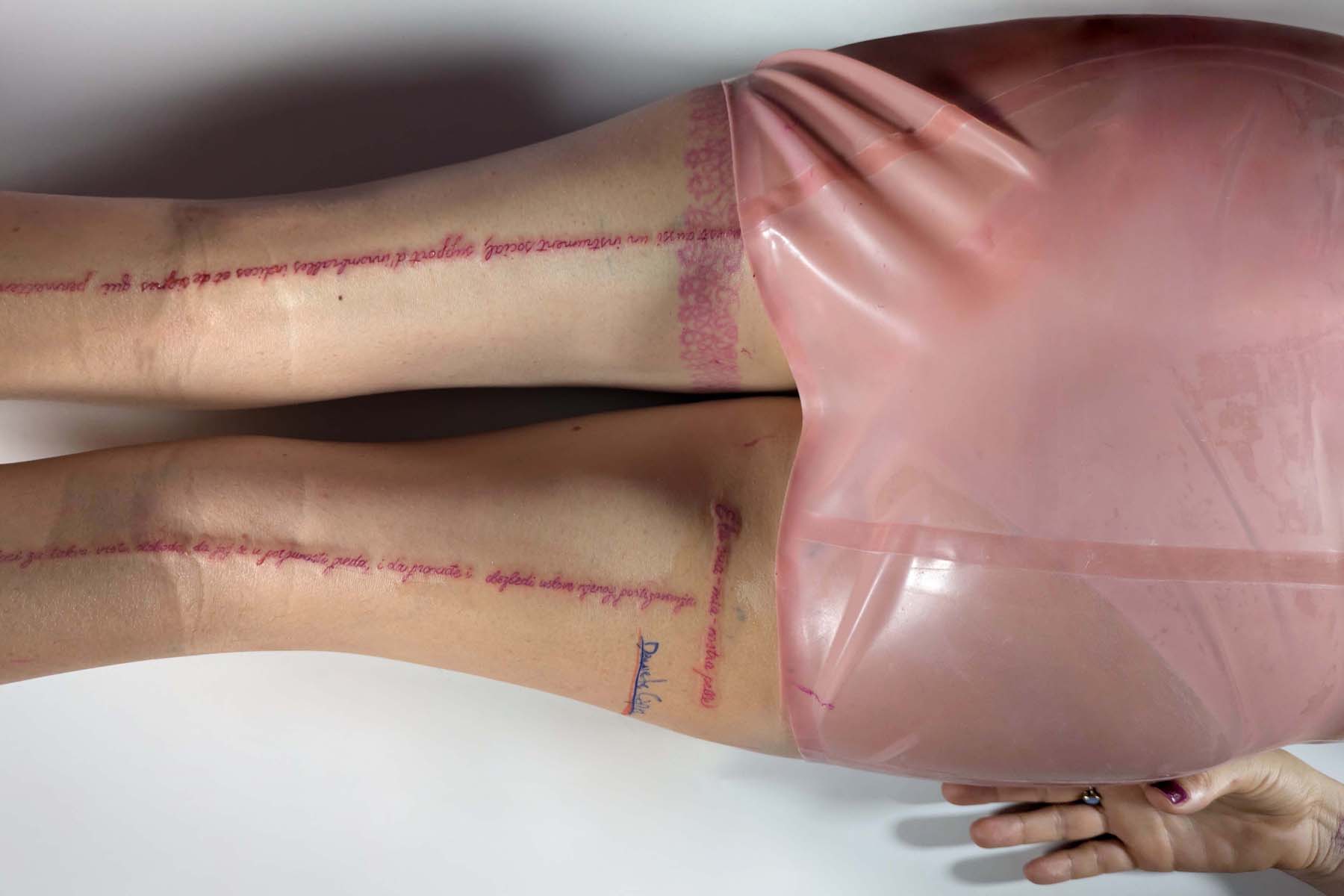

My Skin in Your Eyes

Daniele Capra

I have never found myself writing an exhibition text that does not align with the essayistic style I normally employ in my curatorial work. What I am writing now, in fact, does not conform – in language, tone, or structure – to the ordinary requirements or the institutional expectations that develop through activities related to the artist and the museum. This text is the fruit of a series of personal reflections that have matured over the months leading up to Marina Marković’s exhibition – The Arrangement(s). What is unusual, from my perspective, arises from an expressive urgency and an intimate logic that still partially elude me and will probably continue to foster further discoveries on my part in the years to come. This process was precisely sparked by Marina, [1] who prompted me to imagine writing a text on her body: a concept, a sentence, words, or even punctuation marks that would be tattooed on her skin during her solo exhibition at the Salon of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade. And although this invitation gave me immense pleasure (the pleasure of collaborating with an artist who respects herself, the pleasure of serving as a soldier beside her), what unsettled me was the extraordinary freedom the artist granted me. No limits were imposed on me, except for those inherently dictated by the body itself.

In the past, I have never inscribed someone’s body with coded language or grammar. I came close to it in my youth, in a somewhat clumsy and unconscious way, leaving marks on others’ bodies as a result of accidental and highly intense interactions while playing sports like rugby and basketball. Later, as I matured, this occurred during romantic encounters, where the pursuit of pleasure inadvertently caused bruises, small haematomas, irritations, scratches, and bites on another’s body. Yet, I always felt a sense of shame in leaving even the most fleeting mark on someone’s body. Even with partners who literally asked me to bite them, I restrained myself, because I have always been cautious about anything resembling the desecration of skin, body, and person. For similar reasons, I never wanted to have any sentence, motto, an important name, or image tattooed on myself: I let only the passage of time and the marks it leaves be inscribed on it. Moreover, I have never tolerated the idea of something that remains forever, and although aesthetic surgery now offers the possibility of removal, a tattoo is an indelible mark on the skin, visible even when it is not observed.

Of all our senses, sight and touch represent contrasting modes of interaction with the world. The eyes are organs that operate at a distance, while the skin operates up close. My eye sees only a part of reality or, more precisely, a projection of something that is elsewhere and distant from the eyeball. Sight is a sense that functions on a centrifugal logic, receiving information radiating directly from the place where a phenomenon occurs: in this way, the eye informs me and provides context, thus helping me break the isolation of the part of space in which I live. The skin, in contrast, feels directly upon itself through touch, pressure, or friction, something that acts directly on my body: it records the presence of another in a centripetal form in relation to the phenomenon. It confirms that I exist as a body in that moment. It confirms that, as Jean-Paul Sartre wrote, “I exist my body” and that “my body is used and is known by the Other.” It emphasizes the importance of the fact that “as I am for the Other, the Other is disclosed to me as the subject for whom I am an object.” [2]

I cannot escape this obsession with skin that Marina has incited. I cannot think of anything else and continue to look at the skin on my hands and arms as I type on the computer, never quite grasping the essence of differences in complexion, pigment, sheen, or texture of the skin as I move my forearm, wrist, or fingers. The skin envelops me and insinuates itself into the most diverse parts, spreading and folding according to the movements that part of the body most often makes. For example, the folds between my thumb and index finger are not the same as those on my elbow; and even my posture alters the colour of the skin itself. Namely, although I perceive myself as something permanent, my boundary with the world (which the skin constantly renegotiates) undergoes continual micro-changes, incessant negotiations imposed by my physiology, psychological state, and the activities I engage in, as well as atmospheric and meteorological changes of the place where I am. I continue to look at my palms, observing the traces of folds, the imperfect distribution of lines, and reflecting on my mobile boundaries. Boundaries that are always and only between me and the world, and which you and others usually see only on my head, hands, arms and, more rarely, feet and legs.

The skin holds in my body; it is the external, mobile boundary that confirms the division between myself and the world: it feels touches, caresses, scratches, breath, friction, kisses, bites, sucking, itching, pressure, massages, tickles. It often experiences pleasure from touch and the transmission of information it receives. As Jean-Luc Nancy wrote, “the body delights in being touched. It delights in being squeezed, weighed, thought by other bodies, and being the one that squeezes, weighs, and thinks other bodies. Bodies delight in and are delighted by bodies.” [3] The skin recoils from physical contact, from the intensity of pressure, from the mutual habituation of all the parts that touch. The body, wrapped in skin, delights in sharing its surface and, furthermore, enjoys being the boundary that continuously endures the erasure of boundaries. Thus, if I extend my arm in greeting and we shake hands, our fingers cross boundaries. If we embrace, we cross boundaries. The skin adapts; it is elastic and adjusts to our changing positions by wrapping itself differently. The skin, which protects and separates me from the world, thus allows me to receive directly on my body the imprint left by what is outside us, the foreign mass that physically acts upon me.

Whose skin, then, is it that shapes these hands at this moment as I look at them while writing? Is it the final edge of my body or the first veil of the world? After all, the skin is something personal, mine – so why do I carry it around on my body? Or is it someone else’s, belonging to those who can see it, though not always and everywhere? These two possibilities may not be in opposition, given that the skin, by its very nature, defies the concept of contradiction. It is both mine and not mine at the same time, as it is merely a thin foil that separates the inside and outside surfaces (unlike the famous Möbius strip), but it does not question who the owners are. My skin is thus also yours, and similarly, your skin is mine if we come into contact. But what happens if, instead of touching, the skin is seen only from a distance? Whose is it? By what criteria is it defined?

This is what I ponder as I imagine Marina’s skin, which will be tattooed before my eyes and the eyes of so many spectators who will assist in the performance. Whose skin is the artist’s? It is undoubtedly hers, even in her desire to display it and make it an expressive medium, a manifesto, perhaps even a battleground, by using it for inscribing something. But it is also yours and mine, since we are entrusted with the role of spectators, those who can see the skin swell and turn red under the tattoo artist’s ink-filled needles (and unlike Saint Thomas, we do not need to interact by touch [4]). I believe that for an artist who practices body art, the same rules do not apply as for someone who does not use their body for expressive purposes. Although in most cases, a body artist’s body is solely in their possession, during a performance, it ceases to be just theirs. I imagine Marina’s skin as an alien entity, like an embassy of her body in another country, beyond its original boundaries. When presented in the context of a performance, Marina’s skin becomes public and represents her beyond herself: it is her projection offered to us, transcending the Heimat [5] of her body. And it also belongs to those who will learn about what happened later through stories and visual documentation. It is her-my-our skin.

As part of her exhibition, The Arrangement(s), Marina has decided to be tattooed in front of us, thus exposing herself to our gaze like a lay martyr who testifies with her body to the principles and ideals she believes in. Over the past few weeks, I have been repeatedly asked whether this performance involves feminist criticism of the phenomenon of the male gaze or if she employs it for her expressive purposes. On one hand, I believe the artist is fundamentally free to decide, without any obligations, every aspect of her performance (such as the pose she will assume, her clothes, and the way she will shape her work). On the other hand, I think she uses those very stereotypes to share her content, to be even more viewed, to be – as an artist – more alluring. In a sense, I believe she wants to critique this scheme by adopting and at the same time subverting it. The body, Marina’s primary instrument of expression, is one of the main fields where male dominance is revealed: although, with various distinctions, according to feminist critics, the female body is by definition a passive object. As Laura Mulvey writes in one of the foundational texts of feminist theory, “In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.” [6] The Arrangement(s) embodies this scheme: her skin is indeed displayed and offered on a platter to our eyes, and perhaps to our shameful desires, but her work arises from a clear understanding of these conditions and an intimate goal to overturn them. She is, therefore, not an object on display, not a prisoner of male desires and projections, but a subject who seeks to impose her narrative, opening a discussion on stereotypes of activity/passivity, dominance/submissiveness. Marina is not a kitten sleeping and allowing itself to be petted but a tiger that, while we watch it, fixes us with its gaze.

When I see the words on Marina’s body, I see the image of a body that represents the written text. To be more precise, I do not see the body itself, but the image of a body displaying its surface, that is, exposing its face, with text upon it. The written text is a collection of signs corresponding to sounds and meaning: it is a graphic representation and in itself, an image. The artist’s work is an image formed by the overlap of two different images: the skin is the figurative element that represents itself, while the text is the image we perceive as non-figurative. These are images that my eyes convey to the space within me, which allows the image to be assembled, fixed in memory, and maintained there – based on my experiences, culture, inclinations, phobias, or loves. But I see images, and this implies that neither the body nor the tattooed text is neutral, but rather that they serve the same regulatory conventions and composition rules that apply to images. For example, we can consider the text as the primary subject, while the skin, as a canvas, is almost a landscape. Or we can imagine the text as a repoussoir,[7] of the body, thus taking on the role of the true subject of the work. Indeed, it is difficult to focus simultaneously on the text and the skin, emphasized by the choice of pink colour which does not contrast with the skin’s colour, unlike most tattoos. Additionally, it should be noted that the body is not a blank sheet but has symmetry between the right and left sides, an aspect that can be respected or ignored. However, in the past, the texts Marina tattooed followed the body’s shape and were arranged symmetrically in relation to her physiology. I expect that in this case, too, the words I choose will respect this rule of symmetry. Furthermore, the rule of brevity, as a text that is too long would not provide a coherent image. I wondered if this restriction should be adhered to, and I became convinced that brevity is an element that makes the text physically readable and intellectually comprehensible. However, things have taken a different direction. [8]

As I still watch my fingers typing on the keyboard, I feel the anxiety of the responsibility to choose a text that gradually lightens. I start to think, in the end, that it is Marina who speaks, while I am merely a prompter who offers suggestions from behind the scenes, someone who can at most provide occasional advice to the one on stage. I am a curator and cannot occupy the central place from which the artist is viewed. Truth is not in my head (as suggested by the sinologist Kien from Elias Canetti’s novel Auto-Da-Fé), [9] but out in the world, on the artist’s body, on her skin, which is being coloured pink. Do you not see her-my-your skin gently unfolding before our eyes? Do you not feel my words suddenly becoming ours?

[1] From here on, I will use the artist’s first name instead of her surname (as is recommended in formal contexts) due to our personal and professional closeness. I consider myself an active curator who maintains close relationships with artists. When I think of her, I think of her as ‘Marina.’ Using her surname, Marković, in a text that is not an essay would, in my opinion, be an unnecessary formality.

[2] J.P. Sartre, Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology, New York: Atria Books, 2021, p. 468.

[3] J.L. Nancy, Corpus, New York: Fordham University Press, 2008, p. 117.

[4] The story of Saint Thomas touching Jesus’s body is actually completely unfounded, but the Church has validated it over the centuries. See: G.W. Most, Doubting Thomas, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005.

[5] It is impossible to provide an exact definition of the concept of Heimat that exists in the German language, which can be translated as “homeland, community of homeland members, etc.” (see P. Blickle, Heimat: A Critical Theory of the German Idea of Homeland, Rochester: Camden House, 2002). In this case, I imagine Marina’s Heimat as a body that corresponds solely to her personal needs, much like a house serves its exclusive use.

[6] L. Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, in: Screen, XVI, n. 3, 1975, p. 1.

[7] The repoussoir is “an object along the right or left foreground that directs the viewer’s eye into the composition by bracketing (framing) the edge.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Repoussoir (accessed on 16/06/2024).

[8] Originally, I suggested to Marina that she tattoo “My skin in your eyes,” referring to the viewer whose gaze falls upon the artist’s skin. After that, Marina chose a somewhat longer text, contradicting all my desires for conciseness. As often happens, the artist saw the light before the dawn.

[9] E. Canetti, Auto-Da-Fé, London: Jonathan Cape, 1946. Peter Kien, the protagonist of the book, is an experienced sinologist who, at the beginning of the novel, interacts with the world exclusively through books. After an absurd immersion into the city’s underworld, he reemerges stunned, overwhelmed, and unable to resist the dissolution of reality.